Sporting dog injuries

Know what conditions to look out for and how to best return these canine athletes to good function.

When we think of sports for dogs, we usually think of greyhounds for racing and coursing or luring, field trial dogs for hunting, or even sled dogs in the Iditarod. But within the last 10 years or so, other sports have been gaining in popularity, including agility, flyball, disk dog competitions (Frisbee catching), tracking for search and rescue, dock jumping, and earthdog den trials. More than 940,000 entries in 2,461 American Kennel Club-sponsored agility trials were recorded in 2010 alone.1 Flyball associations are now located in North America, the United Kingdom, Belgium, Australia, South Africa, Germany, Finland, and the Netherlands; in the United States alone, more than 8,000 entries were recorded by the North American Flyball Association.2

With many of these increasingly popular sports, there is no specific breed requirement or physical examination by a veterinarian. A major concern for veterinarians is that little research has been conducted to determine the effect of these sports on the dogs.

With sporting dogs, just as with working dogs, preventive examinations should be as much a part of their training as the actual practice of their sport. In human sports medicine, recommendations are for athletes to be examined biannually.3 No specific guidelines have been established for sporting and working dogs regarding veterinary examination frequency, but young, healthy sporting dogs without previous injuries may be examined as frequently as every six months. During the examination, full general physical, orthopedic, and neurologic examinations should be performed. If a dog has previously been injured but has made a recovery after treatment (Figure 1), whether surgical or rehabilitative, examinations should be performed every three months for as long as the dog is competing or participating in sporting activities.

1. An agility dog competing after the repair of an Achilles tendon injury six months previously.

Injuries can be sustained to a variety of tissues, including bone (fractures), ligament and tendon (tears), the cardiovascular system (dehydration and heat stress), skin (lacerations), and many others. Types of injuries vary according to the sport a dog engages in (see Which injuries are most common in various sports?). In this article, I'll describe common injuries in sporting dogs. And in the next article, I'll discuss how to prevent these injuries.

FOOT PAD INJURIES

Foot pad lacerations and nail trauma are common in sporting dogs. Most of these injuries are treated by the owners themselves, but full-thickness foot pad lacerations through the dermis need surgical closure if the dog is to return to athletics.4 The suture material should be large enough to withstand weight-bearing, and the interrupted mattress suture pattern is best to prevent tearing out of the sutures.4 In addition, a heavily padded splint bandage may be applied during the healing period to reduce weight-bearing and shear stress on the sutures.

Puncture wounds on the palmar or plantar surface of the paw can be problematic since a dog can develop deep digital flexor tendonitis, a potentially career-ending problem. Systemic antibiotics are recommended as well as surgical management with débridement and suturing of the puncture.4 Broad-spectrum antibiotics should be administered while culture and sensitivity test results (culture obtained during débridement procedure) are pending, and then therapy should be based on both aerobic and anaerobic culture results.

FORELIMB INJURIES

Some the most common injuries in sporting dogs involve the shoulder. This is especially true in agility dogs.5 Common shoulder problems include biceps brachii tenosynovitis, supraspinatus insertionopathy, infraspinatus contracture and bursal ossification, teres minor myopathy, and medial shoulder instability (medial glenohumeral ligament sprain, subscapularis tendinopathy, and joint capsule laxity).

Other forelimb injuries in sporting dogs, which have been described elsewhere, include shoulder trauma, elbow injuries, and carpal injuries. Shoulder trauma can result in fracture, osteoarthritis, or luxation. Injuries to the elbow encountered in canine athletes frequently include luxation, medial and lateral collateral ligament rupture, congenital or traumatic fragmented medial coronoid process, or osteoarthritis of unknown cause.4

Biceps brachii tenosynovitis

The biceps brachii originates on the supraglenoid tubercle; passes across the shoulder joint, down the humerus in the intertubercular groove; and inserts on the proximal medial ulna and the proximal cranial radius. Its function is to flex and supinate the elbow, extend the shoulder, and passively stabilize the shoulder in neutral and flexed positions.6,7 Biceps brachii tenosynovitis is usually a chronic injury of the forelimb that develops over time as the tendon tears slowly and then subsequently develops dystrophic mineralization.8 On orthopedic examination, pain will be elicited on palpation of the tendon and flexion of the shoulder joint. In some cases, conservative management will resolve the problem, and some veterinarians recommend rest with one injection of corticosteroids into the shoulder joint, which is confluent with the tendon bursa; however, to my knowledge, no definitive published reports have shown efficacy of corticosteroid injections for biceps tendonitis.8

Rehabilitation, without surgery, often includes therapeutic ultrasound, passive range of motion exercises, strengthening exercises, and underwater treadmill therapy.9

When surgical treatment is indicated, the tendon is released arthroscopically (tenotomy) and may or may not be fixed to the proximal humerus.8 I perform fixation in these cases with a lag screw and washer if the dog's owner is planning to return the dog to sporting activities (Figure 2).10 Rehabilitation, as outlined above, is recommended postoperatively to develop the brachialis muscle that also flexes the elbow and may prevent continued overload of the biceps brachii muscle when the dog uses it to flex the elbow.11

2. A postoperative lateromedial radiograph obtained after arthroscopic tenotomy of the biceps brachii tendon and tenodesis of the tendon to the proximal humeral diaphysis.

The prognosis is good to excellent for most dogs treated surgically with either technique, but their level of performance in athletics after surgery has not been scientifically evaluated.8,10,12 Further research in injured sporting dogs after their performance in athletic competition is needed to determine how well these dogs regain their function as athletes.

Supraspinatus insertionopathy

The supraspinatus muscle originates on the scapula and crosses the shoulder joint cranially to insert on the humerus at the greater tubercle. It functions to extend the shoulder and is a passive stabilizer of the shoulder joint.6 Supraspinatus insertionopathy or tendinopathy involves the supraspinatus tendon becoming torn or strained over time. This chronic injury may not result in lameness until there is ossification of the tendon (Figure 3) and impingement on the biceps brachii tendon, but lameness can occur without ossification.13,14 On physical examination, the dog will exhibit pain when the shoulder is flexed and the tendon is palpated cranially over the shoulder joint; the dog may also exhibit pain when the biceps brachii tendon is palpated.9,15 Supraspinatus tendon injuries can be diagnosed with ultrasonography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and injuries are often bilateral.14

3. A lateromedial radiograph of the shoulder showing ossification of the supraspinatus tendon (arrow).

The decision to treat should be based on a dog's clinical presentation since mineralization of the tendon can be present and identified as an incidental finding on radiographs without any clinical signs of lameness or pain on palpation. Treatment can be aimed at surgical removal of the ossified body, but the condition can recur, and, in one report, three of 16 dogs (19%) had a poor surgical outcome.14 Extracorporeal shock wave therapy, laser therapy, and therapeutic ultrasound have been reported as treatments for the condition, along with underwater treadmill therapy and exercises to restore shoulder function and resolve pain associated with the condition, but prospective placebo-controlled trials have not been reported.9,15,16 In horses, various tendon injuries have been treated successfully with platelet-rich plasma and stem cells; this method of stimulating repair of a strained tendon is currently under investigation in dogs.17-20 For athletes that do not respond to rehabilitation, surgery is recommended to resect the torn or mineralized portion of the tendon.14

Infraspinatus contracture and bursal ossification

The infraspinatus muscle arises from the infraspinatus fossa of the scapula, crosses the shoulder joint, and inserts on the humerus at the greater tubercle just distal to the supraspinatus insertion point.6 This muscle has many functions for the shoulder—flexion and extension, passive stability, and lateral rotation of the forelimb.6 Labrador retrievers and other breeds may develop tendon and bursal ossification of the infraspinatus muscle.9,21 One of the first reports of mineralization of the infraspinatus tendon was in Labrador retrievers; progressive lameness was reported to develop in this breed.21,22 Affected dogs may show no clinical signs, or pain may be present on palpation of the tendon craniolaterally on the shoulder joint, and the dogs may exhibit progressive lameness.21 Diagnostic ultrasound may be used to visualize the damaged tendon and to monitor healing after treatment.23

Some dogs respond to conservative management with rest and corticosteroid injection into the bursa or tendon, while others require surgical resection and release of the tendon. As many as 50% may not fully recover from the condition.21 During arthroscopy, pathology is often noted in other shoulder structures such as the medial glenohumeral ligament or biceps brachii tendon, and these problems may contribute to the patient's lameness and dysfunction.24 The prognosis for return to previous levels of athletic ability in animals with this condition alone is unknown since it frequently occurs with other shoulder pathologies.

Teres minor myopathy

The teres minor muscle flexes the shoulder joint and can slightly rotate the forelimb medially. It arises from the infraglenoid tubercle of the scapula and crosses the shoulder to insert on the lateral diaphysis of the humerus.25 Teres minor myopathy results in a consistent lameness with pain on extension of the shoulder.25 When tissue and muscle just caudal to the acromial process are palpated, sometimes a firm band of tissue and shoulder pain are evident. This condition can be diagnosed by ultrasonographic examination of the tendon and muscle. Conservative management may only be effective early in the course of the disease. If the condition is chronic, surgery is needed to resect the fibrous tissue and tendon.25

Medial shoulder instability

Medial glenohumeral joint laxity, or medial shoulder instability, may be a frequent but underdiagnosed cause of forelimb lameness in athletic dogs.26,27 Careful examination of a sedated dog can identify instability, with abduction angles greater than 40 degrees indicative of pathologic instability (Figure 4).28 Definitive diagnosis can be difficult with stress-view radiographs of the shoulder in abduction since the radiographs are sometimes difficult to interpret.28,29 Secondary changes can be seen with radiographs and are indicative of osteoarthritis, but definitive diagnosis of medial shoulder instability is based on MRI or arthroscopic visualization of the subscapularis tendon, medial glenohumeral ligament, and medial joint capsule pathology.30,31 The weightbearing lameness seen with this instability is often intermittent and occurs after physical activity.

4. A craniocaudal radiograph of the shoulder showing medial glenohumeral instability in a dog.

Numerous treatment methods have been reported, including conservative management with hobbles and cage rest, thermal capsulorrhaphy, prosthetic medial ligament repair, biceps brachii tendon transposition, and subscapularis tendon imbrication.27,32-34 Conservative management has been reported to have a good to excellent outcome in 25% of dogs, whereas surgical treatment has improved outcomes, with 85% to 93% of dogs attaining good or better function.27,32 However, after surgery, some dogs may have continued lameness.27,32,34 Rehabilitation may improve the function and performance of some dogs after recovery from surgery. In severe cases of instability, arthrodesis may be performed, but the dog cannot continue to compete at the same level as before the injury.32

Carpal injury

In the carpus, sporting dogs can incur flexor carpi ulnaris tendinopathy or avulsion, superficial digital flexor tendon elongation (flyball and agility dogs), medial and lateral collateral ligament rupture, abductor pollicis longus tenosynovitis (earthdogs), palmar ligament hyperextension injury (flyball and dock dogs), radial carpal bone luxation or fracture, styloid process fracture and joint instability, or carpal osteoarthritis (racing greyhounds).4,25,35-37

Tendinopathy and even avulsion of the insertion of the flexor carpi ulnaris from the accessory carpal bone can occur in sporting dogs, especially those working on uneven terrain and hard surfaces. In dogs, the injury presents with what looks like hyperextension of the carpus and is differentiated from tears of the flexor retinaculum by palpating distal to the accessory carpal bone (which should palpate normally if the flexor carpi ulnaris is strained or avulsed). If the flexor retinaculum is torn, the dog will stand with the affected limb hyperextended, and there will be swelling or enlargement of the soft tissues on the palmar aspect of the carpus distal to the accessory carpal bone.38

Treatment consists of surgical repair of the avulsion by using a three-loop pulley suture technique (usually with a bone tunnel created in the accessory carpal bone), splinting for three weeks, and then rehabilitation for a gradual return to function.38 Treatment of strains or tendinopathies can be conservative with laser or shockwave therapy used to stimulate healing of the insertion and increase the strength of the healed fibers.39-41 During therapy and for three weeks after treatment, the dog should be maintained in a splint or orthotic brace to support the healing structures.

HINDLIMB INJURIES

In the hindlimb, hip dysplasia and osteoarthritis of the hip, stifle, and tarsus are not uncommon and usually a consequence of preexisting developmental orthopedic disease.42 Sporting dogs can also develop gracilis-semitendinosus myopathy and contracture, iliopsoas muscle trauma leading to femoral neuropathy, cruciate ligament rupture, patellar tendonitis, long digital extensor tendonitis due to proximal luxation, and gastrocnemius head or popliteal muscle avulsion injury.24,36,43,44 Chronic injuries of the hindlimb include Achilles tendon rupture, iliopsoas myopathy, partial cruciate ligament rupture, and lumbosacral disease.5,45,46

Below are specifics on identifying and treating iliopsoas muscle injury, popliteal muscle avulsion, gastrocnemius muscle avulsion, superficial digital flexor tendon luxation, and Achilles tendon injury—conditions many practitioners may not be as familiar with.

Iliopsoas muscle injury

The psoas major muscle arises from the transverse processes of the second and third lumbar vertebrae and the ventral vertebral bodies of the fourth through seventh lumbar; it then joins with the iliacus muscle (which arises from the ilium) to become the iliopsoas muscle that inserts on the lesser trochanter of the femur.6 The femoral nerve passes through the muscle fibers of the psoas and iliopsoas muscles, and with hemorrhage in this area or tearing of the muscle, compression and stretching of the nerve from the hematoma may cause a femoral neuropathy.44,47,48

Injury to the iliopsoas muscle is not as uncommon as once thought.49 Dogs that are infrequently active and overextend themselves can experience this injury as well as athletes. Affected dogs may not be lame but may show signs of decreased performance, difficulty rising, and a shortened stiff gait in the hindlimbs.50 In severe cases, they may have signs of femoral nerve paralysis. A sprain of the muscle will be mildly painful on palpation, but when there has been hemorrhage into the muscle fibers, severe pain can be present because of compression and inflammation of the closely related femoral nerve.47

The injury can be diagnosed on ultrasonographic examination.49 Treatment of mild cases often involves therapeutic ultrasonography, passive range of motion exercises, and a gradual return to activity.49 If this therapy fails, surgical resection of the iliopsoas tendon of insertion can resolve the clinical signs.47

Popliteal muscle avulsion

The popliteal muscle flexes the stifle and internally rotates the tibia in relation to the femur. It originates on the lateral femoral condyle with its sesamoid near its origin, crosses the stifle joint caudally, and then inserts on the proximal medial tibia.6

When avulsion occurs, it is at the lateral femoral condyle, and pain will be present on extension of the stifle as well as when the caudal aspect of the stifle is palpated.51 On radiographs, the popliteal sesamoid at the caudal aspect of the stifle joint will be displaced distally. Surgery to reattach the muscle to the lateral femoral condyle is recommended, but as with gastrocnemius avulsion (see below), return to peak performance is unlikely.4

Gastrocnemius muscle avulsion

The gastrocnemius muscle originates in two heads, one on each supracondylar tuberosity, and each contains one sesamoid, called a fabella. The muscle tendon inserts on the calcaneal bone to extend the tarsus and flex the stifle.6

Avulsion of the gastrocnemius muscle at its head results in an acute nonweightbearing lameness, while partial avulsion in which some of the origin of the muscle remains attached to the femur results in partial weightbearing. The hock may be hyperflexed in some dogs when they try to bear weight on the limb because the gastrocnemius muscle functions to flex the stifle.52,53 On radiographs of the stifle, one or both of the fabellae may be distally displaced.

Conservative management of partial avulsions with therapeutic ultrasound and rest can resolve clinical signs of lameness in some dogs.54 Surgical reattachment of the muscle head to the supracondylar femur and restriction of stifle extension for three weeks postoperatively are recommended in athletes. The lameness will resolve, but dogs rarely return to their previous performance level.24

Superficial digital flexor tendon luxation

Collies and Shetland sheepdogs are becoming increasingly popular in flyball and agility sports and are more prone to lateral luxation of the superficial digital flexor tendon than are other breeds.55 The superficial digital flexor arises from the lateral supracondylar tuberosity of the femur and the lateral fabella, crosses the stifle joint and lies proximally cranial to the gastrocnemius, and then passes medially to the caudal aspect of the gastrocnemius tendon as it courses distally. The superficial digital flexor tendon continues distally after inserting on the tuber calcanei to insert on the proximal caudal border of the second phalange.6

The luxation occurs at the level of the calcaneal bone where the retinaculum ruptures. The dog will exhibit pain and lameness in the hindlimb and may have its toes elevated off the floor when standing on the affected limb. The diagnosis is made by palpation of the area where the tendon can be replaced and luxated again, similar to a luxating patella.55

Treatment involves surgical repair of the retinaculum by suturing it over the tendon by using simple interrupted or cruciate sutures with absorbable monofilament suture material. The tendon itself is not sutured so that it may continue to glide over the calcaneal bone and function to flex the digits and extend the tarsus. After surgical repair, rehabilitation and a gradual return to activity are recommended.4

Achilles tendon injury

The Achilles tendon, also called the common calcaneal tendon, is composed of three tendinous structures including the gastrocnemius tendon, the superficial digital flexor tendon, and the common tendon of the biceps femoris, gracilis, and semitendinosus muscles. This tendon is most frequently injured by laceration in both dogs and cats.56 Chronic and acute injuries of the Achilles tendon may occur. Acute injuries are most commonly due to lacerations and often occur within 48 hours before presentation. Subacute injuries have occurred at any time between two and 21 days, and chronic injuries are older than 21 days.57

Subacute and chronic injury pathogenesis and diagnosis. The pathogenesis of subacute or chronic injuries not associated with laceration of the tendon is not well understood. Progressive rupture of the Achilles tendon can develop over time, with injury most commonly to the gastrocnemius component affected.56 Suspected initiators of such chronic ruptures have included chronic corticosteroid ingestion and fluoroquinolone (even one dose in people may cause tendon damage) administration.58,59 Most veterinary cases are in large-breed, active dogs and may be related to chronic repetitive injury during exercise.57

Progressive Achilles tendon rupture is diagnosed on physical examination and confirmed with radiography and ultrasonography. Examination may reveal changes in posture with hock hyperflexion, with or without excessive digit flexion, and, possibly, a plantigrade stance. Palpation of the tendon may reveal thickening, thinning, or a normal-sized tendon. Ultrasonographic findings may include signs of hemorrhage, fiber disruption, and scar tissue formation (Figures 5A & 5B).60,61 Normal tendon diameter as seen on transverse ultrasound images has been established at 2.4 to 3.2 mm.62

5A & 5B. Longitudinal (proximal is to the left, and caudal is across the top) images of ultrasonographic examination of the distal Achilles tendon in a Labrador retriever: 5A) The tendon without significant abnormalities. 5B) The contralateral tendon of same dog with marked fiber disruption and fluid present at the former insertion of the tendon to the calcaneal bone.

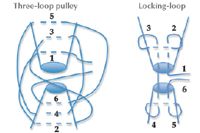

Treating tendon rupture. Surgical treatment is preferred over conservative medical management in cases of complete gastrocnemius tendon rupture.56,63 In people, dogs, and cats, primary repair of the tendon is performed and most commonly involves one of two different suture techniques: the three-loop pulley or the locking-loop suture pattern (Figure 6). Both patterns have superior strength compared with other patterns used in the past, but the locking loop may have improved resistance to gap formation with loading of the tendon.64 A gap between the torn tendon ends or tendon end and calcaneal bone of less than 3 mm allows strength and stiffness to increase, with a decrease in repair failure during the first six weeks after surgery.65 All sutures involved in the primary repair are recommended to be nonabsorbable monofilament suture in order to allow gliding motion along the suture, but sustain reapposition of the tendon ends for at least three weeks.56

6. The three-loop pulley (left) and locking-loop (right) suture techniques for tendon anastomosis.

Tendon repair augmentation. Augmentation of the primary repair is controversial. Acute lacerations or injuries of less than 48 hours' duration usually are not augmented. Subacute or chronic lacerations are most often augmented with various implants or tissues intended to remain permanently at the repair site.61,63 Biological implants include free fascia lata graft, porcine small intestinal submucosa, or the semitendinosus muscle.66 Injection of the tendon repair with concentrated platelet gel has been advocated to speed healing postoperatively, but, to my knowledge, no controlled studies have proven its effectiveness in tendon healing in dogs.67 Porcine small intestinal submucosa has been used experimentally in dogs and facilitates complete tendon healing within 90 days of the surgically created Achilles tendon defect.68

Postoperative care and return to function. Protection of the repair early in the healing process is a must. Additional support can be from a cast, external skeletal fixator, splint, or calcaneal-tibial bone screw. All of these methods provide relief of tension on the repair for three weeks to three months after surgery.56,69 Many practices support the repaired tendon with an orthotic such as a neoprene brace, hinged splint, or other custom-made device so that the dog may again begin training as soon as possible.

Immobilization for longer than four weeks will result in deleterious effects on the joints, some of which can be permanent.70 In addition, early mobilization of the joint improves the healing process and augments the tensile strength of the tendon repair.67,71,72 The average length of time that some form of immobilization is needed is about 10 weeks, but most surgeons decrease the amount of support incrementally over that time. A dog may achieve a stable functional hindlimb after repair, but return to competition is less likely than return to function as a pet. A study from New Zealand determined that only seven of 10 dogs returned to full or substantial levels of work after healing, and 29% of those had moderate persistent lameness.46

New methods to enhance and speed healing of tendon repairs are being investigated. Low energy shock wave therapy may enhance neovascularization of the bone-tendon junction in dogs.73 Ultrasound therapy may be able to accelerate healing and tendon maturation in dogs as well.74 While no clinical studies exist, future developments and methods of postoperative care may improve the functional outcome in small animals with Achilles tendon injuries.

CONCLUSION

This review describes a wide range of causes of lameness in sporting dogs, but many new conditions will be identified as the popularity of dog sports continues to increase. A thorough physical examination and an investigation of intermittent lameness in sports dogs early in the course of their disease can prolong their athletic careers and may even improve performance. Diagnosis of these conditions should involve any appropriate combination of radiography, ultrasonography, nuclear scintigraphy, computed tomography, MRI, and arthroscopy, among other diagnostic tools. Further research is needed to determine the best treatment options for these dogs, but new developments continue to be investigated.

Of course, preventing injury in these canine athletes is the primary goal of owners, trainers, and veterinarians. See the related article "Preventing injury in sporting dogs" for measures you can recommend clients take to help their dogs stay healthy and injury-free as they participate in sports.

Wendy Baltzer, DVM, PhD, DACVS

Department of Clinical Sciences

College of Veterinary Medicine

Oregon State University

Corvallis, OR 97331

REFERENCES

1. American Kennel Club. AKC agility stats. Available at: http://www.akc.org/pdfs/events/agility/2010_stats.pdf.

2. Association NAF. Flyball Growth Trends: NAFA, http://www.flyball.org, 2008.

3. American Academy of Pediatrics. Sports medicine: health care for young athletes. 2nd ed. Elk Grove Village, Ill: American Academy of Pediatrics, 1991.

4. Bloomberg MS, Taylor RA, Dee JF. Canine sports medicine and surgery. 1st ed. St. Louis, Mo: W.B. Saunders Co, 1998.

5. Levy M, Hall C, Trentacosta N, et al. A preliminary retrospective survey of injuries occurring in dogs participating in canine agility. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol 2009;22(4):321-324.

6. Evans HE. Arthrology. In: Miller's anatomy of the dog. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: W.B. Saunders, 1993;233-236.

7. Sidaway BK, McLaughlin RM, Elder SH, et al. Role of the tendons of the biceps brachii and infraspinatus muscles and the medial glenohumeral ligament in the maintenance of passive shoulder joint stability in dogs. Am J Vet Res 2004;65(9):1216-1222.

8. Stobie D, Wallace LJ, Lipowitz AJ, et al. Chronic bicipital tenosynovitis in dogs: 29 cases (1985-1992). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1995;207(2):201-207.

9. Marcellin-Little DJ, Levine D, Canapp SO Jr. The canine shoulder: selected disorders and their management with physical therapy. Clin Tech Small Anim Pract 2007;22(4):171-182.

10. Cook JL, Kenter K, Fox DB. Arthroscopic biceps tenodesis: technique and results in six dogs. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2005;41(2):121-127.

11. Millis DL, Levine D, Taylor RA. Canine rehabilitation and physical therapy. 1st ed. St. Louis, Mo: Saunders, 2004.

12. Wall CR, Taylor R. Arthroscopic biceps brachii tenotomy as a treatment for canine bicipital tenosynovitis. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2002;38(2):169-175.

13. Fransson BA, Gavin PR, Lahmers KK. Supraspinatus tendinosis associated with biceps brachii tendon displacement in a dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2005;227(9):1429-1433.

14. Lafuente MP, Fransson BA, Lincoln JD, et al. Surgical treatment of mineralized and nonmineralized supraspinatous tendinopathy in twenty-four dogs. Vet Surg 2009;38(3):380-387.

15. Danova NA, Muir P. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy for supraspinatus calcifying tendinopathy in two dogs. Vet Rec 2003;152(7):208-209.

16. Saunders DG, Walker JR, Levine D. Joint mobilization. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2005;35(6):1287-1316.

17. Sanchez M, Anitua E, Azofra J, et al. Comparison of surgically repaired Achilles tendon tears using platelet-rich fibrin matrices. Am J Sports Med 2007;35(2):245-251.

18. Waselau M, Sutter WW, Genovese RL, et al. Intralesional injection of platelet-rich plasma followed by controlled exercise for treatment of midbody suspensory ligament desmitis in Standardbred racehorses. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2008;232(10):1515-1520.

19. Dyson SJ. Medical management of superficial digital flexor tendonitis: a comparative study in 219 horses (1992-2000). Equine Vet J 2004;36(5):415-419.

20. Richardson LE, Dudhia J, Clegg PD, et al. Stem cells in veterinary medicine—attempts at regenerating equine tendon after injury. Trends Biotechnol 2007;25(9):409-416.

21. McKee WM, Macias C, May C, et al. Ossification of the infraspinatus tendon-bursa in 13 dogs. Vet Rec 2007;161(25):846-852.

22. McKee, WM, May C, Macias C. Infraspinatus bursal ossification (IBO) in eight dogs, in Proceedings. First World Orthopaedic Veterinary Congress, 2002;141.

23. Siems JJ, Breur GJ, Blevins WE, et al. Use of two-dimensional real-time ultrasonography for diagnosing contracture and strain of the infraspinatus muscle in a dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1998;212(1): 77-80.

24. Rochat MC. Emerging causes of canine lameness. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2005;35(5):1233-1239.

25. Bruce WJ, Spence S, Miller A. Teres minor myopathy as a cause of lameness in a dog. J Small Anim Pract 1997;38(2):74-77.

26. Bardet JF. Diagnosis of shoulder instability in dogs and cats: a retrospective study. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 1998;34(1):42-54.

27. Cook JL, Tomlinson JL, Fox DB, et al. Treatment of dogs diagnosed with medial shoulder instability using radiofrequency-induced thermal capsulorrhaphy. Vet Surg 2005;34(5):469-475.

28. Cook JL, Renfro DC, Tomlinson JL, et al. Measurement of angles of abduction for diagnosis of shoulder instability in dogs using goniometry and digital image analysis. Vet Surg 2005;34(5):463-468.

29. Puglisi TA, Tangner CH, Green RW, et al. Stress radiography of the canine humeral joint. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 1988;24(2):235-240.

30. Schaefer SL, Forrest LJ. Magnetic resonance imaging of the canine shoulder: an anatomic study. Vet Surg 2006;35(8):721-728.

31. Martini FM, Pinna S, Del BM. A simplified technique for diagnostic and surgical arthroscopy of the shoulder joint in the dog. J Small Anim Pract 2002;43(1):7-11.

32. Pucheu B, Duhautois B. Surgical treatment of shoulder instability. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol 2008;21(4):368-374.

33. O'Neill T, Innes JF. Treatment of shoulder instability caused by medial glenohumeral ligament rupture with thermal capsulorrhaphy. J Small Anim Pract 2004;45(10):521-524.

34. Pettitt RA, Clements DN, Guilliard MJ. Stabilisation of medial shoulder instability by imbrication of the subscapularis muscle tendon of insertion. J Small Anim Pract 2007;48(11):626-631.

35. Blythe LL, Gannon JR, Craig AM, et al. Care of the racing and retired greyhound. 1st ed. Abilene, Kan: American Greyhound Council, Inc, 2007.

36. Marcellin-Little DJ, Levine D, Taylor R. Rehabilitation and conditioning of sporting dogs. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2005;35(6):1427-1439.

37. Grundmann S, Montavon PM. Stenosing tenosynovitis of the abductor pollicis longus muscle. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol 2001;14:95-100.

38. Kuan SY, Smith BA, Fearnside SM, et al. Flexor carpi ulnaris tendonopathy in a Weimaraner. Aust Vet J 2007;85(10):401-404.

39. Wang L, Qin L, Lu HB, et al. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy in the treatment of delayed bone-tendon healing. Am J Sports Med 2008;36(2):340-347.

40. Venzin C, Ohlerth S, Koch D, et al. Extracorporeal shockwave therapy in a dog with chronic bicipital tenosynovitis. Schweiz Arch Tierheilkd 2004;146(3):136-141.

41. Enwemeka CS, Parker JC, Dowdy DS, et al. The efficacy of low-power lasers in tissue repair and pain control: a meta-analysis study. Photomed Laser Surg 2004;22(4):323-329.

42. Todhunter RJ, Johnston SA. Osteoarthritis. In: Slatter D, ed. Textbook of small animal surgery. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders, 2003;2208-2246.

43. Steiss JE. Muscle disorders and rehabilitation in canine athletes. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2002;32(1):267-285.

44. Rossmeisl JH Jr, Rohleder JJ, Hancock R, et al. Computed tomographic features of suspected traumatic injury to the iliopsoas and pelvic limb musculature of a dog. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 2004;45(5):388-392.

45. Pfau T, Garland de Rivaz A, Brighton S, et al. Kinetics of jump landing in agility dogs. Vet J 2011;190(2):278-283.

46. Worth AJ, Danielsson F, Bray JP, et al. Ability to work and owner satisfaction following surgical repair of common calcanean tendon injuries in working dogs in New Zealand. N Z Vet J 2004;52(3):109-116.

47. Stepnik MW, Olby N, Thompson RR, et al. Femoral neuropathy in a dog with iliopsoas muscle injury. Vet Surg 2006;35(2):186-190.

48. Reinstein L, Alevizatos AC, Twardzik FG, et al. Femoral nerve dysfunction after retroperitoneal hemorrhage: pathophysiology revealed by computed tomography. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1984;65(1):37-40.

49. Breur GJ, Blevins WE. Traumatic injury of the iliopsoas muscle in three dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1997;210(11):1631-1634.

50. Adrega Da Silva C, Bernard F, Bardet JF, et al. Fibrotic myopathy of the iliopsoas muscle in a dog. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol 2009;22(3):238-242.

51. Eaton-Wells RD, Plummer GV. Avulsion of the popliteal muscle in an Afghan Hound. J Small Anim Pract 1978;19(12):743-747.

52. Muir P, Dueland RT. Avulsion of the origin of the medial head of the gastrocnemius muscle in a dog. Vet Rec 1994;135(15):359-360.

53. Prior JE. Avulsion of the lateral head of the gastrocnemius muscle in a working dog. Vet Rec 1994;134(15):382-383.

54. Mueller MC, Gradner G, Hittmair KM, et al. Conservative treatment of partial gastrocnemius muscle avulsions in dogs using therapeutic ultrasound—a force plate study. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol 2009;22(3):243-248.

55. Mauterer JV Jr, Prata RG, Carberry CA, et al. Displacement of the tendon of the superficial digital flexor muscle in dogs: 10 cases (1983-1991). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1993;203(8):1162-1165.

56. King M, Jerram R. Achilles tendon rupture in dogs. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet 2003;25:613-620.

57. Reinke JD, Mughannam AJ, Owens JM. Avulsion of the gastrocnemius tendon in 11 dogs. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 1993;29:410-418.

58. Maffulli N. Rupture of the Achilles tendon. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1999;81(7):1019-1036.

59. Leppilahti J, Orava S. Total Achilles tendon rupture. A review. Sports Med 1998;25(2):79-100.

60. Rivers BJ, Walter PA, Kramek B, et al. Sonographic findings in canine common calcaneal tendon injury. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol 1997;10:45-53.

61. Swiderski J, Fitch RB, Staatz A, et al. Sonographic assisted diagnosis and treatment of bilateral gastrocnemius tendon rupture in a Labrador retriever repaired with fascia lata and polypropylene mesh. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol 2005;18(4):258-263.

62. Lamb CR, Duvernois A. Ultrasonographic anatomy of the normal canine calcaneal tendon. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 2005;46(4):326-330.

63. Shani J, Shahar R. Repair of chronic complete traumatic rupture of the common calcaneal tendon in a dog using a fascia lata graft. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol 2000;13:104-108.

64. Moores AP, Owen MR, Tarlton JF. The three-loop pulley suture versus two locking-loop sutures for the repair of canine Achilles tendons. Vet Surg 2004;33(2):131-137.

65. Gelberman RH, Boyer MI, Brodt MD, et al. The effect of gap formation at the repair site on the strength and excursion of intrasynovial flexor tendons. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1999;81(7):975-982.

66. Baltzer WI, Rist P. Achilles tendon repair in dogs using the semitendinosus muscle: surgical technique and short-term outcome in five dogs. Vet Surg 2009;38(6):770-779.

67. Virchenko O, Aspenberg P. How can one platelet injection after tendon injury lead to a stronger tendon after 4 weeks? Acta Orthop 2006;77(5):806-812.

68. Gilbert TW, Stewart-Akers AM, Simmons-Byrd A, et al. Degradation and remodeling of small intestinal submucosa in canine Achilles tendon repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2007;89(3):621-630.

69. Nielsen C, Pluhar GE. Outcome following surgical repair of achilles tendon rupture and comparison between postoperative tibiotarsal immobilization methods in dogs: 28 cases (1997-2004). Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol 2006;19(4):246-249.

70. Haapala J, Arokoski JP, Hyttinen MM, et al. Remobilization does not fully restore immobilization induced articular cartilage atrophy. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1999;(362):218-229.

71. Enwemeka CS. Functional loading augments the initial tensile strength and energy absorption capacity of regenerating rabbit Achilles tendons. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 1992;71(1):31-38.

72. Murrell GA, Lilly EG 3rd, Goldner RD, et al. Effects of immobilization on Achilles tendon healing in a rat model. J Orthop Res 1994;12(4):582-591.

73. Wang CJ, Huang HY, Pai CH. Shock wave-enhanced neovascularization at the tendon-bone junction: an experiment in dogs. J Foot Ankle Surg 2002;41(1):16-22.

74. Saini NS, Roy KS, Bansal PS, et al. A preliminary study on the effect of ultrasound therapy on the healing of surgically severed achilles tendons in five dogs. J Vet Med A Physiol Pathol Clin Med 2002;49(6):321-328.