Cardiac tumors in dogs and cats

Considerations for the use of echocardiography to evaluate suspected tumors located in the heart.

Although rare in veterinary medicine, cardiac tumors can cause life-threatening complications, including pericardial effusion and tamponade, congestive heart failure, blood flow obstruction, and arrhythmias.1-5 However, because presenting clinical signs in patients with cardiac tumors are usually nonspecific, a low level of suspicion often hampers diagnosis.

Reports from owners may include hyporexia, lethargy, weakness, neurologic signs, vomiting, and abdominal distention. Except for abdominal distention and perhaps weakness, however, none of these signs are likely to prompt a clinician to image the heart.5-7 Triage of emergent patients by point-of-care focused cardiac ultrasound has revolutionized the ability to diagnose pericardial effusion in clinical practice, overcoming the deficiencies of low sensitivity and specificity reported with thoracic radiography.2,8,9

The leading cause of pericardial effusion in dogs is cardiac neoplasia. Over 70% of cases have either right atrial or heart-based masses, often concurrent with pleural effusion, ascites or, more commonly, tricavitary effusions.7 Pericardial effusion is reported in at least 16% of all dogs diagnosed with cardiac tumors on necropsy, whereas 42% of dogs with antemortem echocardiographic diagnosis, later confirmed by necropsy or cytology, have a concurrent pericardial effusion.5,7 Arrhythmias are reported in dogs associated with hemangiosarcoma and chemodectoma, with ventricular ectopy or tachycardia most frequently described. Other findings include electrical alternans in dogs with concurrent pericardial effusions and, rarely, supraventricular tachycardia, atrial fibrillation, and atrioventricular and bundle branch blocks.2-4

The role of echocardiography

Echocardiography is the screening test of choice in dogs with pericardial effusion. Similarly, dogs presenting with dysrhythmias require echocardiography as structural heart diseases, including infiltrative tumors, are considered possible etiologies. Echocardiography has its limitations, but because antemortem confirmation of a cardiac tumor is rarely obtained by cytology or biopsy, necropsy is often the only means of confirming the diagnosis. Echocardiography is considered moderately accurate, with 86% agreement on location and only 65% agreement on tissue-type diagnosis when compared with necropsy.5 Diagnostic accuracy vastly improves in the presence of pericardial effusion, with a reported sensitivity of 82% and specificity of 100% for detection of a cardiac mass.2

Echocardiography can provide information on the mobility, infiltrative nature, attachment to, and hemodynamic consequences of a cardiac mass.10 Despite the high specificity quoted, the differential diagnosis should include infectious vegetations and sterile thrombi. Due to the inherent risk for false-negative echocardiographic diagnoses, particularly in the absence of pericardial effusion, it is always prudent to keep cardiac neoplasia as a potential diagnosis despite apparent negative findings on echocardiography. Factors such as patient signalment and the high rate of pericardial effusion recurrence may increase the suspicion of a tumor. In mesothelioma, a solid mass may not be visible, and this neoplasia should remain a potential working diagnosis.11 It is worth noting that these results are operator dependent and reports are based on data collected from presumptive diagnoses made by board-certified cardiologists.

Tumor classification and echocardiographic phenotype

Cardiac tumors are either primary or secondary (metastatic) and benign or malignant.6,12 Clinical diagnosis in dogs is predominantly of primary and malignant tumors, with the most common etiologies being hemangiosarcoma followed by chemodectoma (also known as a neuroendocrine tumor, chromaffin cell tumor, aortic body tumor, and carotid body tumor). Cardiac metastatic disease may be more prevalent and silent than clinically seen, with up to 86% of cardiac tumors in dogs diagnosed as metastatic at the time of necropsy and 36% of malignant neoplasias metastasizing to the heart.6,7,13 In cats, cardiac tumors are almost exclusively primary and the majority are extranodal lymphomas.6,14,15 Excluding lymphomas, which tend to develop at an earlier age, cardiac tumors usually affect dogs ranging in age from 7 to 15 years.7 There is no reported gender predisposition, and the risk may be lower in intact animals.7 Breed consideration is important; breeds with reported high cardiac tumor incidence include the Saluki, French bulldog, Irish water spaniel, flat-coated retriever, golden retriever, boxer, Afghan hound, English setter, Scottish terrier, Boston terrier, bulldog, and German shepherd.7

Knowledge of the echocardiographic phenotypic appearance of cardiac tumors is helpful to the clinician, as it remains the undisputed antemortem diagnostic test of choice for this condition. This understanding will allow the clinician to provide appropriate treatment options and give an estimate of prognosis. As noted earlier, antemortem cytologic and histologic diagnosis is often not possible.

Treatment and prognosis

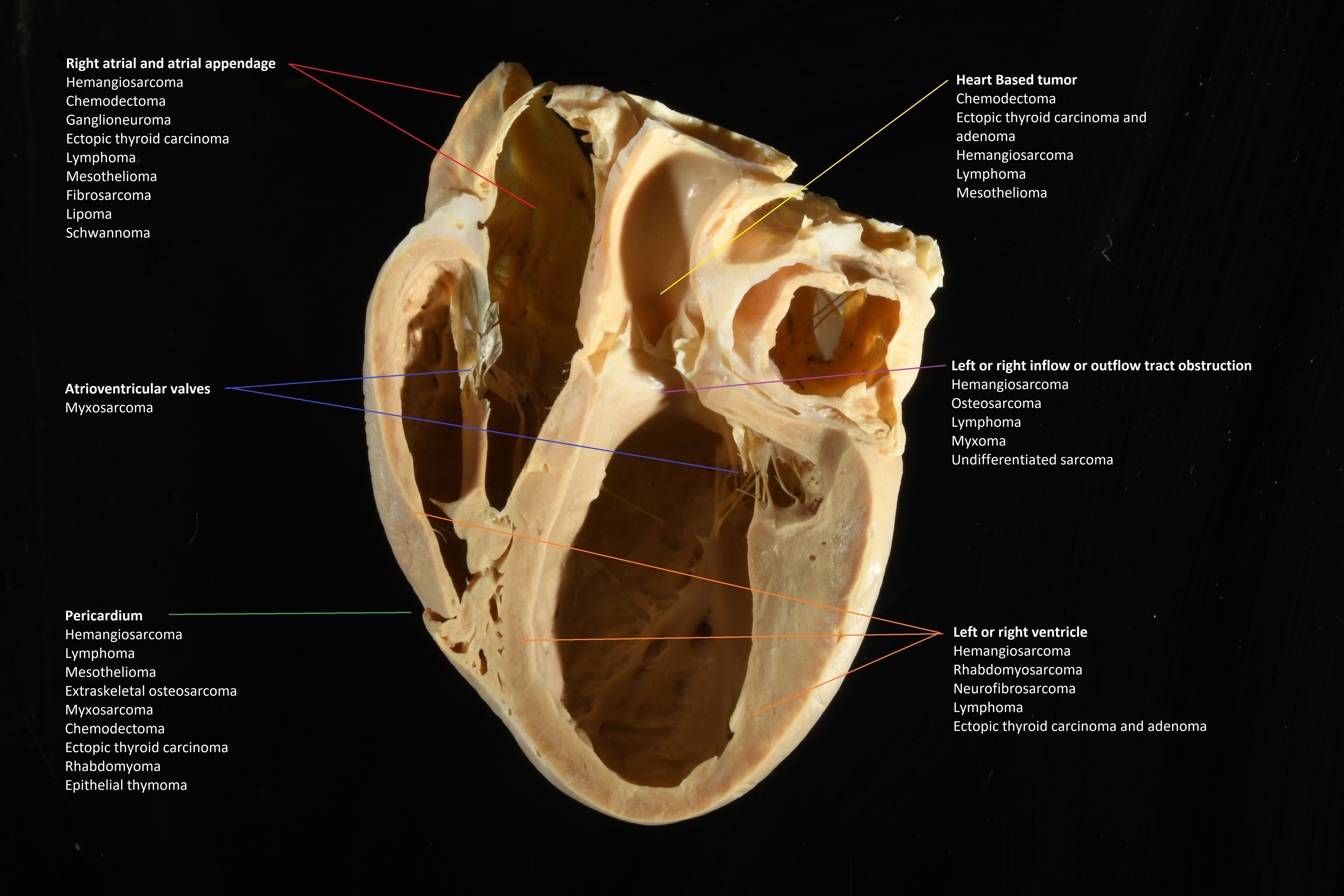

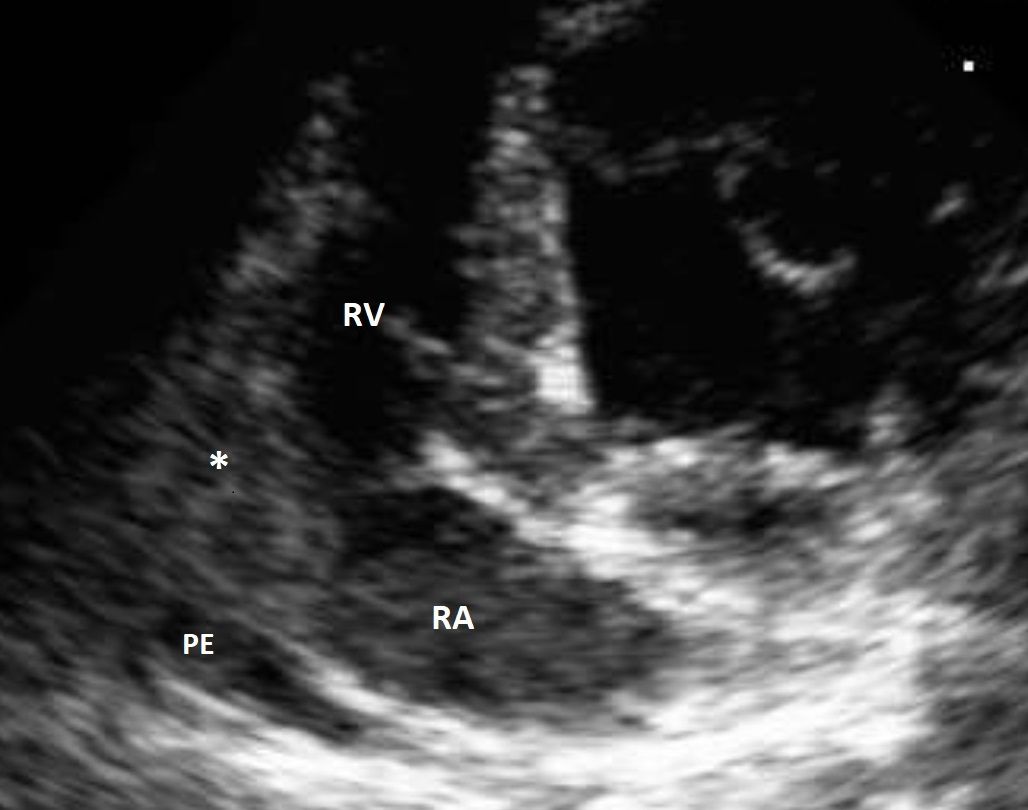

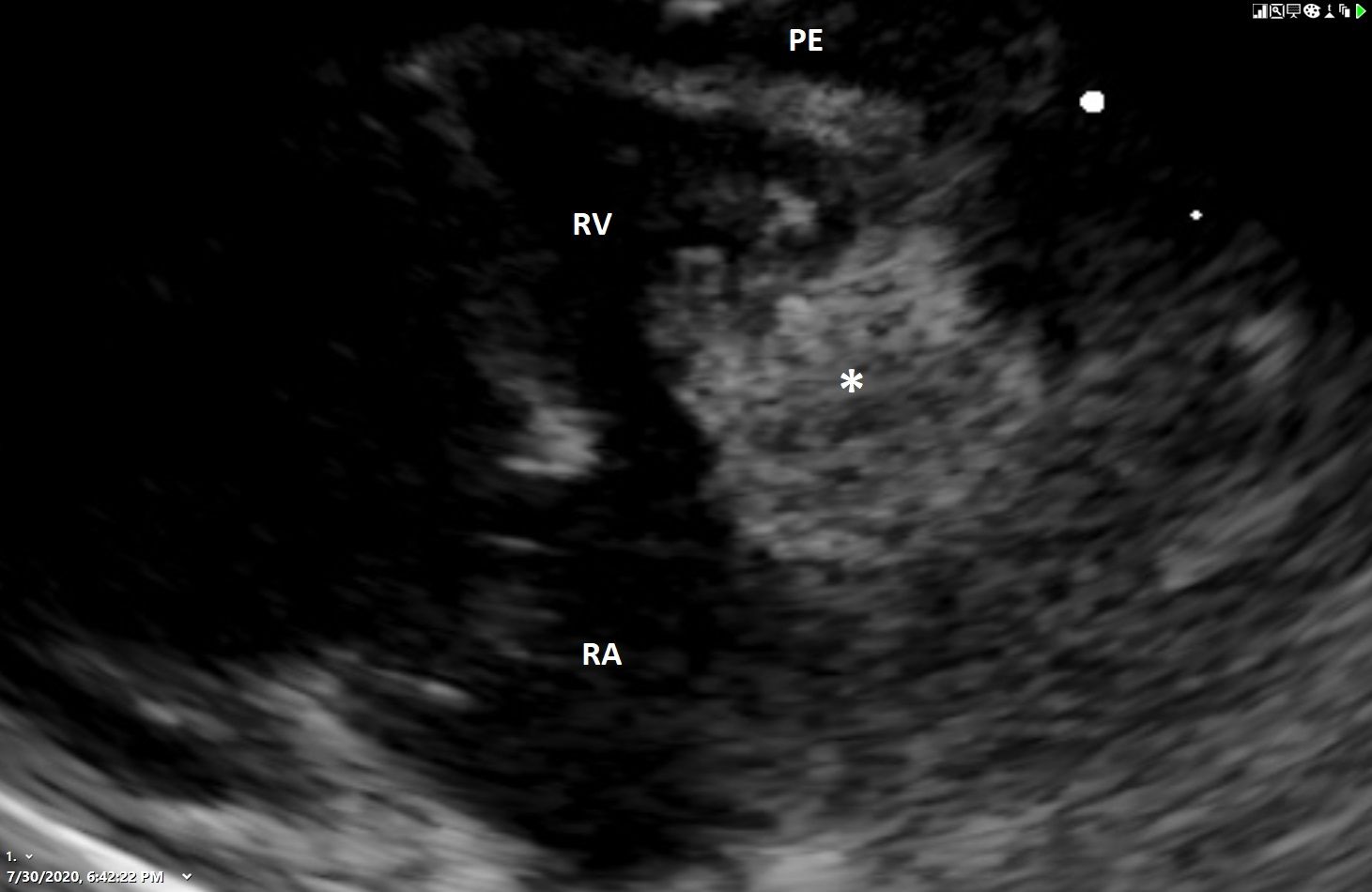

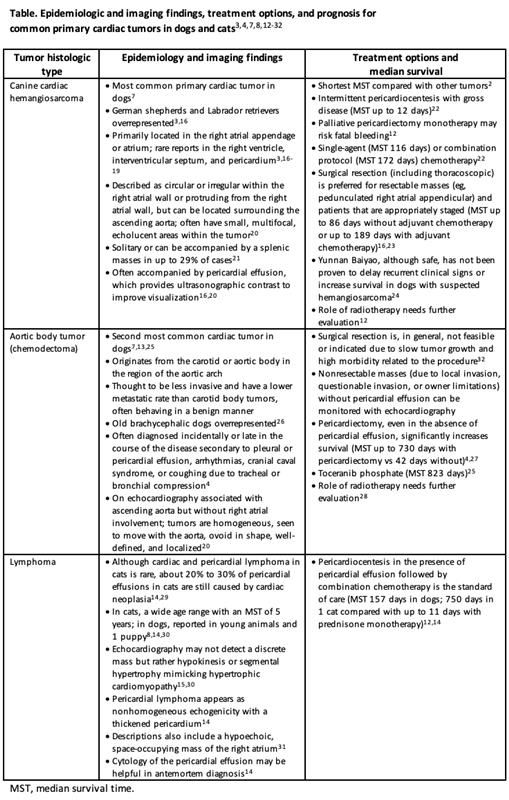

Tumors are often described according to anatomic location (Figure 1), including right atrium, heart base, inflow or outflow tract of the left or right heart chambers, atrioventricular valves, ventricular walls (including the interventricular septum), and pericardium. Tumor histologic prediction is invariably made by a combination of signalment, echocardiographic phenotype, and anatomic location within the heart. Treatment options and prognosis for the most common cardiac tumors seen in dogs and cats are described in the Table.12 (Figures 2 to 4) depict the typical echocardiographic appearance of the most common cardiac neoplasia encountered in small animal practice: hemangiosarcoma, aortic body tumor, and lymphoma.

Figure 1. Locations of presumptive and definitive primary cardiac tumors according to echocardiographic anatomic location in dogs and cats. All images courtesy of Liza S Köster, BVSc(Hons).

Figure 2. Left apical 4-chamber view with the right heart chambers depicted on the left side of the image, the right ventricle in the near field, and the right atrium in the deeper field. A roughly circular, well-defined hypoechoic mass (asterisk) can be seen in the junction between the right atrium and ventricle; the mass is heterogeneous due to multifocal hypoechoic areas. A moderate-volume pericardial effusion is visible as the anechoic area surrounding the heart. The echocardiographic diagnosis in this geriatric German shepherd dog was a right atrial mass; due to tumor location and patient signalment, the tentative diagnosis was hemangiosarcoma.

Figure 3. Left intercostal long-axis view depicting the left ventricular outflow tract. A well-demarcated, homogeneous, soft tissue mass (asterisk) can be seen along the ascending aorta. The echocardiographic diagnosis in this middle-aged boxer was a heart base tumor. Based on the mass location and patient signalment, the tentative diagnosis was an aortic body tumor (chemodectoma). The differential diagnosis would include an ectopic thyroid carcinoma or adenoma.

Figure 4. Left intercostal view of the right ventricle (RV) and atrium (RA) depicting the RV in the near field and the RA and atrial appendage in the far field. Trace pericardial effusion is visible as the anechoic stripe between the pericardium and RV. The asterisk indicates hyperechoic segmental thickening of the RV and atrial wall. The tentative diagnosis in this geriatric domestic shorthair cat was an extranodal lymphoma. Pericardial fluid analysis may have provided cytologic evidence of this tumor, but it was not attempted due to the scant volume.

Tumors are often described according to anatomic location (Figure 1), including right atrium, heart base, inflow or outflow tract of the left or right heart chambers, atrioventricular valves, ventricular walls (including the interventricular septum), and pericardium. Tumor histologic prediction is invariably made by a combination of signalment, echocardiographic phenotype, and anatomic location within the heart. Treatment options and prognosis for the most common cardiac tumors seen in dogs and cats are described in the Table.12 (Figures 2 to 4) depict the typical echocardiographic appearance of the most common cardiac neoplasia encountered in small animal practice: hemangiosarcoma, aortic body tumor, and lymphoma.

Conclusion

Although uncommon, cardiac tumors can have catastrophic consequences for dogs and cats. Knowledge of the sonographic appearance and location of cardiac tumors can help the clinician make a tentative diagnosis. Although invaluable when formulating appropriate management and treatment options, consider the limitations of echocardiography.

Liza S Köster, BVSc(Hons), MMedVet(Med), DECVIM-CA, (Cardiology and Internal Medicine), EBVS, a 1999 graduate of the University of Pretoria (South Africa) Faculty of Medicine, is a clinical assistant professor of cardiology at the University of Tennessee College of Veterinary Medicine.

P. Brent Lawson, DVM, is a 2019 University of Tennessee College of Veterinary Medicine. After practicing for a year, he returned to the university for a rotating internship. He is currently completing his internship with hopes of pursuing a residency in cardiology.

Josep Aisa, DVM, DECVS, a 1999 graduate from the University of Barcelona, is an assistant professor in small animal surgery (soft tissue) at the University of Tennessee College of Veterinary Medicine.

References

1. Warman SM, McGregor R, Fews D, Ferasin L. Congestive heart failure caused by intracardiac tumours in two dogs. J Small Anim Pract. 2006;47(8):480-483. doi:10.1111/j.1748-5827.2006.00149.x

2. MacDonald KA, Cagney O, Magne ML. Echocardiographic and clinicopathologic characterization of pericardial effusion in dogs: 107 cases (1985-2006). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2009;235(12):1456-1461. doi:10.2460/javma.235.12.1456

3. Aronsohn M. Cardiac hemangiosarcoma in the dog: a review of 38 cases. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1985;187(9):922-926.

4. Ehrhart N, Ehrhart EJ, Willis J, et al. Analysis of factors affecting survival in dogs with aortic body tumors. Vet Surg. 2002;31(1):44-48. doi:10.1053/jvet.2002.29989

5. Rajagopalan V, Jesty SA, Craig LE, Gompf R. Comparison of presumptive echocardiographic and definitive diagnoses of cardiac tumors in dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2013;27(5):1092-1096. doi:10.1111/jvim.12134

6. Aupperle H, März I, Ellenberger C, Buschatz S, Reischauer A, Schoon HA. Primary and secondary heart tumours in dogs and cats. J Comp Pathol. 2007;136(1):18-26. doi:10.1016/j.jcpa.2006.10.002

7. Ware WA, Hopper DL. Cardiac tumors in dogs: 1982-1995. J Vet Intern Med. 1999;13(2):95-103. doi:10.1892/0891-6640(1999)013<0095:ctid>2.3.co;2

8. Ward JL, Lisciandro GR, Ware WA, et al. Evaluation of point-of-care thoracic ultrasound and NT-proBNP for the diagnosis of congestive heart failure in cats with respiratory distress. J Vet Intern Med. 2018;32(5):1530-1540. doi:10.1111/jvim.15246

9. Côté E, Schwarz LA, Sithole F. Thoracic radiographic findings for dogs with cardiac tamponade attributable to pericardial effusion. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2013;243(2):232-235. doi:10.2460/javma.243.2.232

10. Mankad R, Herrmann J. Cardiac tumors: echo assessment. Echo Res Pract. 2016;3(4):R65-R77. doi:10.1530/ERP-16-0035

11. McDonough SP, MacLachlan NJ, Tobias AH. Canine pericardial mesothelioma. Vet Pathol. 1992;29(3):256-260. doi:10.1177/030098589202900312

12. Treggiari E, Pedro B, Dukes-McEwan J, Gelzer AR, Blackwood L. A descriptive review of cardiac tumours in dogs and cats. Vet Comp Oncol. 2017;15(2):273-288. doi:10.1111/vco.12167

13. Janus I, Nowak M, Noszczyk-Nowak A, et al. Epidemiological and pathological features of primary cardiac tumours in dogs from Poland in 1970-2014. Acta Vet Hung. 2016;64(1):90-102. doi:10.1556/004.2016.010

14. Amati M, Venco L, Roccabianca P, Santagostino SF, Bertazzolo W. Pericardial lymphoma in seven cats. J Feline Med Surg. 2014;16(6):507-512. doi:10.1177/1098612X1350619

15. Carter TD, Pariaut R, Snook E, Evans DE. Multicentric lymphoma mimicking decompensated hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in a cat. J Vet Intern Med. 2008;22(6):1345-1347. doi:10.1111/j.1939-1676.2008.0208.x

16. Yamamoto S, Hoshi K, Hirakawa A, Chimura S, Kobayashi M, Machida N. Epidemiological, clinical and pathological features of primary cardiac hemangiosarcoma in dogs: a review of 51 cases. J Vet Med Sci. 2013;75(11):1433-1441. doi:10.1292/jvms.13-0064

17. Thompson DJ, Cave NJ, Scrimgeour AB, Thompson KG. Haemangiosarcoma of the interventricular septum in a dog. N Z Vet J. 2011;59(6):332-336. doi:10.1080/00480169.2011.609479

18. Choate CJ, Brinkman-Ferguson E. What is your diagnosis? Cardiac hemangiosarcoma. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2011;238(11):1407-1408. doi:10.2460/javma.238.11.1407

19. Gunasekaran T, Olivier NB, Smedley RC, Sanders RA. Pericardial effusion in a dog with pericardial hemangiosarcoma. J Vet Cardiol. 2019;23:81-87. doi:10.1016/j.jvc.2019.01.008

20. Thomas WP, Sisson D, Bauer TG, Reed JR. Detection of cardiac masses in dogs by two-dimensional echocardiography. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 1984;25(2):65-72. doi:10.1111/j.1740-8261.1984.tb01911.x

21. Boston SE, Higginson G, Monteith G. Concurrent splenic and right atrial mass at presentation in dogs with HSA: a retrospective study. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2011;47(5):336-341. doi:10.5326/JAAHA-MS-5603

22. Mullin CM, Arkans MA, Sammarco CD, et al. Doxorubicin chemotherapy for presumptive cardiac hemangiosarcoma in dogs. Vet Comp Oncol. 2016;14(4):e171-e183. doi:10.1111/vco.12131

23. Weisse C, Soares N, Beal MW, Steffey MA, Drobatz KJ, Henry CJ. Survival times in dogs with right atrial hemangiosarcoma treated by means of surgical resection with or without adjuvant chemotherapy: 23 cases (1986-2000). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2005;226(4):575-579. doi:10.2460/javma.2005.226.575

24. Murphy LA, Panek CM, Bianco D, Nakamura RK. Use of Yunnan Baiyao and epsilon aminocaproic acid in dogs with right atrial masses and pericardial effusion. J Vet Emerg Crit Care (San Antonio). 2017;27(1):121-126. doi:10.1111/vec.12529

25. Lew FH, McQuown B, Borrego J, Cunningham S, Burgess KE. Retrospective evaluation of canine heart base tumours treated with toceranib phosphate (Palladia): 2011-2018. Vet Comp Oncol. 2019;17(4):465-471. doi:10.1111/vco.12491

26. Hayes HM. An hypothesis for the aetiology of canine chemoreceptor system neoplasms, based upon an epidemiological study of 73 cases among hospital patients. J Small Anim Pract. 1975;16(5):337-343. doi:10.1111/j.1748-5827.1975.tb05751.x

27. Vicari ED, Brown DC, Holt DE, Brockman DJ. Survival times of and prognostic indicators for dogs with heart base masses: 25 cases (1986-1999). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2001;219(4):485-487. doi:10.2460/javma.2001.219.485

28. Magestro LM, Gieger TL, Nolan MW. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for heart-base tumors in six dogs. J Vet Cardiol. 2018;20(3):186-197. doi:10.1016/j.jvc.2018.04.001

29. Davidson BJ, Paling AC, Lahmers SL, Neslon OL. Disease association and clinical assessment of feline pericardial effusion. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2008;44(1):5-9. doi:10.5326/0440005

30. Kimura Y, Harada T, Sasaki T, Imai T, Machida N. Primary cardiac lymphoma in a 10-week-old dog. J Vet Med Sci. 2018;80(11):1716-1719. doi:10.1292/jvms.18-0272

31. Tong LJ, Bennett SL, Thompson DJ, Adsett SL, Shiel RE. Right-sided congestive heart failure in a dog because of a primary intracavitary myocardial lymphoma. Aust Vet J. 2015;93(3):67-71. doi:10.1111/avj.12289

32. Orton EC. Cardia neoplasia. In: Orton EC, Monnet E (eds). Small Animal Thoracic Surgery. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2018:231-236.

Veterinary Heroes: Ann E. Hohenhaus, DVM, DACVIM (Oncology, SAIM)

December 1st 2024A trailblazer in small animal internal medicine, Ann E. Hohenhaus, DVM, DACVIM (Oncology, SAIM), has spent decades advancing the profession through clinical expertise, mentorship, and impactful communication.

Read More