The burden of care: Know the risks to your mental health

Mental health isnt an issue that affects just a few isolated individuals. Its something the entire veterinary profession needs to be aware ofthat is, if it wants to protect its members from depression and a staggeringly high risk for suicide.

Getty Images

Veterinarians rely on evidence-based methodology. It's rational. It reveals the problem. It points to the solution.

When it comes to mental health, the evidence is that veterinarians are at a higher risk for depression and suicide than the general population and even other healthcare professionals. This was painfully illustrated in two high-profile suicides this past year, which have prompted the profession to begin to acknowledge and address its own problems with mental and emotional health.

But many veterinarians-whether they're experiencing burnout, compassion fatigue, depression or even suicidal ideation-still have a similar reaction: inaction. The evidence may reveal the problem, but the culture of the veterinary profession, for many, obscures the solution.

A house built on sand

There are plenty of factors that can erode well-being in the veterinary profession. Isolation, financial burdens, difficult client interactions, business-related challenges, stigmas associated with seeking help, and a high exposure to death may all contribute to emotional and mental instability among those in the profession.

Dr. Steve Noonan

Steve Noonan, DVM, a certified career coach who has experienced depression, says a veterinarian's job is extremely challenging. “The bond can be stressful. The economy can be stressful. The demand for performance can be stressful. Terminating life and being bummed out about that is stressful,” Noonan says. “Life has put us on a treadmill. Because of technology, we're available 24/7 and access to information is expanding at an exponential rate. We're expected to know everything and expected to be available always.”

Dr. Jennifer Brandt

Jennifer Brandt, PhD, LISW, veterinary social worker at the College of Veterinary Medicine at Ohio State University, says mental health problems act as a foundation of sand underneath the weight of the veterinary profession's demands. “It will hold up until put under pressure,” she says. “It's like many professions that require a low margin for error and are very demanding.”

Past research indicates that veterinarians in the United Kingdom are four times more likely to commit suicide than the general population and two times more likely than other healthcare professionals.1 Australian research has also found that the suicide rate among veterinarians is four times that of adults in other professions.2

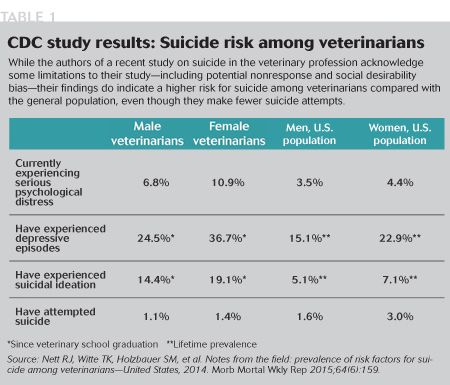

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published the most recent study on veterinary mental health in February.3 It received survey responses from about 10 percent of all employed U.S. veterinarians and found that nearly one in 10 were currently experiencing psychological distress and more than one in six have experienced suicidal ideation since veterinary school graduation-results that are much higher than those of the general population (see Table 1, below).

Dr. Laurie Fonken

“The responses that they got are alarming,” says Laurie Fonken, PhD, veterinary student psychological counselor at the Colorado State University College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences. “The numbers get people's attention, but the underlying issues are where we need to focus.”

High risk

Factors and opinions on who in the veterinary profession is most at risk for depression-and specifically suicide-vary. One study suggests that veterinarians are most likely to first experience suicidal thoughts during their transition from training to practice.1

“The pressure to perform increases once they're out in practice,” Fonken says. Young veterinarians are dealing with things that aren't always addressed in school-staff relations, finances. And the safety net of the academic environment is gone.

Fonken says these new graduates don't feel like doctors yet. They are worried about hurting patients and consumed by performance anxiety. Plus, they may be discovering that veterinary medicine isn't the career they expected. “They have this vision of what their life is going to be like,” she says. “But they feel like they can't let anyone down. They feel trapped, like there's no way out.”

Another high-risk group may be veterinarians practicing in low socioeconomic areas. One Australian study found that veterinarians practicing in these communities experienced a suicide risk almost double that of veterinarians practicing in average-income areas and nearly four times that of those practicing in high socioeconomic neighborhoods.4

The same study concluded that objectionable euthanasia was not related to mental health concerns. But Noonan doesn't quite buy it. He says veterinarians struggle with horrendous guilt over the euthanasia of healthy or treatable animals, not to mention the emotions that often follow euthanasia of terminal or chronically ill patients as well. “I've had days when I've euthanized 10 animals-it's extremely stressful,” he says.

Culture of silence

One piece of data that may trump all others is from a U.K. study. In that investigation, of veterinarians with a history of suicidal thoughts or behavior, half had not talked with anyone about their problems because they felt guilty or ashamed.1

“Veterinarians are lone wolves. They like to go into a corner and lick their wounds,” Noonan says. “Companionship and community lead to positivity and happiness, but veterinarians are introverts and soloists.”

Fonken says veterinarians are highly driven perfectionists and high achievers. “It's hard for them to ask for help,” she says. The stigma is that a veterinarian who admits a need for help is weak or vulnerable. So they tell themselves, “I'm just going to power through this and not let anybody know,” Fonken says.

Brandt says the people who are most at risk are those that are isolated. “If you're in your truck working solo every day, it's hard to recognize changes until you find yourself at rock bottom,” she says.

Fonken says veterinarians often believe they're the only one experiencing these feelings and that they should handle it on their own. “Work harder, try harder, and no one will know” is often the mantra, she says.

Emotional and physical isolation, especially in solo practice, can also be dangerous because of the doctor's easy access to medications. One study found that deliberate self-poisoning (most often from barbituates) accounted for 76 to 89 percent of suicides in male and female veterinarians compared with 20 to 46 percent in men and women in the general population.1

Veterinarians' silence may also be attributed to a fear that reaching out will affect their job-or that they simply don't have time. “If you have a 20 hour workday and that's what's expected of you, how do we get to you?” Brandt says. “If you had pneumonia, you would go to the doctor. If you had a broken leg, you would go to the doctor. Is there adequate time off to see a mental health professional? We need to create meaningful life balance to create those opportunities.”

Make the time

“We always want to think we're doing better than we are,” Fonken says. “We don't always realize how many down days we're having.” And the excuses come easily: I don't have time. It's not that bad. It will get better.

After all, sometimes it does. Taking a new job at another clinic, practicing better self-care habits such as exercising and getting more sleep, or talking to a trusted friend of family member can all help the malaise remain manageable.

But often it doesn't get better. And that's when emotional imbalance can become a deeper mental health concern. “If you hit that burnout and can't get out of it, that's a danger sign,” Fonken says. “It can easily slip from situational to prolonged depression requiring therapy and medication.”

In most cases, time is what severe depression needs to take hold. And severe depression, over time and without treatment, allows suicidal ideation to creep in.

Suicide

It's often a combination of time and suffering without relief-the same problems recurring-that causes the system to overload, Brandt says. The kind of depression that leads someone to consider suicide involves feelings of ceaseless despair, hopelessness that things will never change, and fears of being a burden on others.

But it's hard to know definitively what drives veterinarians specifically toward suicide more than other groups. Some have suggested that veterinarians' attitude toward euthanasia alters their perspective. In veterinary medicine, euthanasia is often seen as a gift. Fonken says she spoke with a veterinarian dealing with a parent's terminal illness who found herself wishing she could create a peaceful end like she could in her own practice: “[She was] wishing euthanasia in humans was more accepted. It's an end to suffering.”

Fonken says deep depression creates a dull numbness those suffering from it can't think or act their way out of. Suicide is seen as the only way out. “The lens they see the world through is gray,” Fonken says. “They don't want to die. They just want to escape from the pain.”

Conversation peaked on the topic of suicide after the deaths of Shirley Koshi, DVM, and Sophia Yin, DVM, MS, this past year. Koshi's death in February 2014 occurred after an ownership dispute involving a cat that resulted in a lawsuit and intense negative online campaigns against her.

Yin was a well-known pet-behavior expert and a leader in the profession when she took her own life last September. She published her work in a number of journals, wrote three books, produced training videos and worked in private practice. “The loss of her really resonated,” Brandt says. “It definitely raised awareness.”

Brandt says Yin's death was a horrible event that spurred needed conversations. Many people found themselves asking how such a visible, active and influential member of the veterinary profession could be at risk for suicide. Those closer to Yin, who knew her as a driven perfectionist, say she struggled with developing personal relationships outside the profession and with feelings of inadequacy. Still, none of them could have predicted the outcome.

Noonan says those in despair are often good at hiding it. At the bottom of his own depression, hiding became part of his routine. “You have to be a really good actor, but at the end of the day, you hate yourself even more,” Noonan says. “You feel worse because you weren't true to yourself.”

Offer help

Both Brandt and Fonken encourage veterinarians to reach out to coworkers they think may be depressed. “You don't have to diagnose,” Brandt says. She suggests starting out this way: “I've noticed that you … appear tired, have been wearing the same outfit for three days, are tearful … ” Then say, “I'm concerned about you. How can I help?”

Fonken agrees, saying this may just help the person reach the point where he or she is ready to ask for help.

But help may be a tricky concept for the veterinary mind. “Very high achievers will come in saying, ‘I'm juggling 17 balls and an 18th has come along. How do I juggle 18 balls?'” Brandt says. But juggling 18 balls is not the answer-maybe they need to get down to 10.

“We make the load more manageable so if another stressor comes along we have room to manage,” Brandt says. “This is a give, give, give profession, so sometimes being told to put one of those balls down isn't failing anybody. It really does feel like a relief.”

Noonan says the highly driven veterinary mind can also be an asset when it comes to understanding your own mental illness. The desire to learn, know and understand can be an ally. “I've learned everything I can about my condition,” he says.

Noonan says, of anyone, veterinarians are capable of pulling themselves from the depths of mental illness. “The veterinarian lands the 747 when the pilot has a heart attack. Vets can do everything,” he says. “You either help yourself or get help from a medical professional or both. People are amazingly resourceful. It can be done.”

The old model

Fonken says the CSU veterinary program is focusing on equipping students with the skills and resources they'll need for mental and emotional health when they graduate. But her students often tell her they have no role models exercising self-care and they have no time to do it.

“A lot of the change needs to change with the institution-the profession. We have to practice what we preach,” Fonken says. “Students walk out of my office and they see the faculty doing what I tell them not to do. We're hypocrites.”

But self-care is hard to achieve in a profession of workaholics, Fonken says. “ They work so hard and under so much pressure-it's hard to leave the office,” she says. “It's hard to say, ‘I have to go home.'” This becomes a vicious cycle. But if you don't care for yourself, at some point you won't be able to care for others.

Of course, there's a common opinion-reflected by some in the 2015 dvm360 Job Satisfaction Survey-that those with problems should just “put on your doctor coat and buck up.”

“That used to be the model-get over it,” Fonken says. The new model-at least at CSU and other veterinary schools-is quite different. It's about awareness, education and normalizing common struggles.

Brandt says veterinary students exposed to mental health education and wellness techniques have a greater confidence level in coming forward with their own problems. “Seeking help becomes a priority,” she says. “It really has been a significant shift. It's been touching to my heart.”

Hope for change

Colleges of veterinary medicine like those at Ohio State and Colorado State have been proactive when it comes to providing mental health resources and education for students. “We are doing so much more,” Brandt says. “At the veterinary school level, most or all offer personal development classes that cover suicide prevention. That wasn't done before. Now it's part of the curriculum.”

But Fonken wishes that veterinary professionals outside academia received more education on mental illness, self-care and how to seek help. “Once our students graduate, they're on their own and that's when they need somebody,” she says. “They lose all their support.”

Still, she hopes that infusing more wellness education into the veterinary school curriculum will normalize self-care and lead to a healthier model for the veterinary profession.

“Statistically, there will always be a percentage that have mental health issues,” Brandt says. “My hope is that we will detect issues earlier and provide intervention earlier so it won't lead to suicide and [veterinarians will have] more satisfaction in life.”

The mental health data collected 10 years from now may show improvement with the focus on wellness and education in veterinary schools today, but those on the front lines know building a stronger foundation for mental wellness in the veterinary profession is a daunting but important mission. “My goal is to graduate healthy human beings to be solid veterinarians,” Fonken says. “It's going to be a long-term change.”

References

1. Bartram DJ, Baldwin DS. Veterinary surgeons and suicide: A structured review of possible influences on increased risk. Vet Rec 2010;166(15):451.

2. Jones-Fairnie H, Ferroni P, Silburn S, et al. Suicide in Australian veterinarians. Aust Vet J 2008;86(4):114-16.

3. Nett RJ, Witte TK, Holzbauer SM, et al. Notes from the field: prevalence of risk factors for suicide among veterinarians-United States, 2014. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015;64(6):159.

4. Tran L, Crane MF, Phillips JK. The distinct role of performing euthanasia on depression and suicide in veterinarians. J Occup Health Psychol 2014; 19(2):123-32.