Canine urolithiasis overview and update (Proceedings)

During the past three decades, a tremendous amount of information has been generated regarding the etiology, detection, treatment, and prevention of canine urolithiasis.

During the past three decades, a tremendous amount of information has been generated regarding the etiology, detection, treatment, and prevention of canine urolithiasis. No longer is surgical removal the only option available when dogs develop urolithiasis, nor is surgical removal the "treatment" of choice" in all patients. Although we know a lot more information about urolithiasis in dogs than we did three decades ago, there is still a lot that we don't know and remains to be discovered. Nonetheless, our ability to medically manage this disease in dogs has dramatically improved since 1973, and new knowledge continues to be generated. The purpose of the lecture is to provide an overview and an update on therapeutic options available for the four most common mineral types of uroliths in dogs.

Canine Urolithiasis Overview Table

Distribution of Mineral Types of Canine Urolths:

In 2003, the distribution of canine uroliths (n = 28,629) submitted to the Minnesota Urolith Center (courtesy of Dr. Carl Osborne and The Minnesota Urolith Center) were as follows:

Since 1981, prevalence of calcium oxalate in dogs has continued to increase, and it is equal to that of struvite now.Successful long-term management of urolithiasis is dependent upon an understanding of each mineral type.

Struvite (Magnesium Ammonium Phosphate) Urolithiasis

1. Background Information

- the majority of struvite uroliths in dogs are infection-induced.

- urinary tract infections with urease-producing bacteria, such as staphlococci or proteus, result in

urine becoming supersaturated with ammonium ions by the following reaction:

- when urine becomes supersaturated with ammonium ions (NH4+ ), these NH4+ can combine with

- magnesium and phosphate already present in urine, resulting in the formation of Magnesium

- Ammonium Phosphate uroliths.

- therefore, successful management and dissolution of infection-induced struvite urolithiasis in dogs

- is dependent upon appropriate treatment of the UTI along with dietary intervention.

2. Medical Dissolution Protocol

A. Drug intervention

- successful dissolution of infection-induced struvite uroliths is dependent upon eradicating the UTI that caused it to occur in the first place.

- appropriate antibiotic therapy, based on urine culture and sensitivity results, is a critical component of medical dissolution.a urine culture should be obtained pre-antibiotic treatment once dogs are receiving the appropriate antibiotic, the urine should be re-cultured 5 to 7 days later to ensure that the urine is sterile.

if the urine is not sterile by this time (5 to 7 days), you have a treatment failure (owner noncompliance, inappropriate dose, dog spitting antibiotic out, etc) and you need to re-evaluate your therapy.

- keep in mind that a urinalysis is not a sensitive way to evaluate whether the urine is sterile or not; therefore, a urine culture is necessary for monitoring a UTI.

- if the urine is sterile after 5 to 7 days of antibiotic therapy, continue administering antibiotics during the entire dissolution period.bacteria are often seeded throughout the entire stone, and therefore as you dissolve layers of the stone, you continually release bacteria into the urine.

B. Dietary intervention

- the main diet used for dissolution of struvite uroliths in dogs is Hill's Prescription Diet s/d, although Waltham S/O Lower Urinary Tract Support can also be use.

- some very important points to keep in mind about Hill's Prescription Diet s/d are:

o /d is very high in fat, and therefore it is contraindicated in any dogs with a history of pancreatitis or hyperlipidemia

o although the development of pancreatitis in dogs consuming s/d is relatively uncommon, it can nonetheless occur.

o dogs should be gradually transitioned from their current diet to s/d over the course of 7 to 10 days.

o if at any time the dog starts to vomit, discontinue s/d and monitor for pancreatitis

- s/d is very low in protein, and is not meant to be used long-term (>6 months)

- it is contraindicated to supplement dogs with methionine that are consuming s/d.

C. Recheck protocol

- the larger the stone, the longer it will take to dissolve

- many dogs become asymptomatic long before all of their stones are dissolved.

- recommend monthly rechecks and obtain at a minimum a lateral abdominal radiograph and a urine culture

- once stones no longer visible on radiographs, continue dissolution protocol (antibiotics and s/d) for an additional "insurance" month to ensure microscopic crystalline material not visible on radiographs dissolve.

3. Prevention of Recurrence

- The single most important thing to do to prevent recurrence of infection-induced struvite urolithiasis is to prevent UTI and retreat promptly if it recurs.

- if a dog had infection-induced struvite urolithiasis, once stones are successfully dissolved, I usually do not recommend feeding an acidifying therapeutic diet, but rather suggest they feed whatever diet they were feeding prior to developing stones or some other maintenance diet.

- Many of the breeds that we see with increased risk for developing struvite uroliths are also breeds with increased risk for developing calcium oxalate uroliths.

- If a dog had rare sterile struvite stones, then dietary management may be necessary to prevent recurrence.

Calcium Oxalate Urolithiasis

1. Background Information

- the majority of dogs diagnosed with calcium oxalate urolithiasis are not hypercalcemic

- proposed reasons for why some normocalcemic dogs develop calcium oxalate uroliths are:

o excessive GI absorption of calcium (intestinal hyperabsorption of calcium)

o excessive renal loss of calcium

o defective nephrocalcin, a glycoprotein that inhibits calcium oxalate crystal growth

2. Medical Dissolution Protocol

- currently, calcium oxalate uroliths in dog can not be medically dissolved.

- therapeutic options available

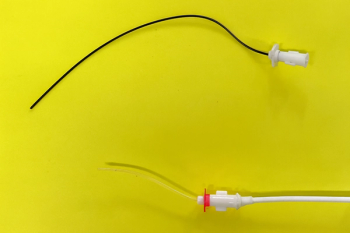

o if stones are detected when they are small enough, they may be able to be removed via a urinary catheter or by voiding urohydropropulsion (Lulich JP. VCNA Small Anim Prac 29:283-292, 1999)

o if stones are too large to be removed non-surgically, and the dog is symptomatic, it may be necessary to initially remove all the stones surgically, and then take appropriate dietary and monitoring steps to detect recurrence of stones when they are small enough to remove non-surgically (i.e. via urinary catheter or voiding urohydropropulsion).

A. Recurrence of calcium oxalate uroliths in dogs is common. In 1992, Lulich published an abstract (JVIM) that revealed that recurrence rates of calcium oxalate uroliths in dogs 12 months after surgery was 36%, after 24 months was 42%; and after 36 months was 48%.

B. Despite high recurrence rate, the following steps can be taken to reduce the likelihood of having to perform repeated cystotomies

- diet should have the following characteristics: protein-restricted; alkalinizing, low in oxalate; not calcium-restricted, sodium-restricted; and canned if client can afford.

- one diet that meets these criteria is Hill's Prescription Diet u/d. This diet is protein-restricted, however the amount of protein in this diet is high enough that it can be used long-term

- Hill's Prescription Diet u/d & Waltham S/O Lower Urinary Support are both high in fat contraindicated in patients with a history of pancreatitis or hyperlipidemia

- Hill's Prescription Diet w/d* can be used in patients where a high-fat diet is contraindicated

* this diet is an acidifying diet, and therefore should be used in combination with

potassium citrate

, which is primarily used for its alkalinizing properties.

3. Recheck Protocol

- Although calcium oxalate uroliths can not be dissolved medically, additional surgeries in dogs can be avoided by diligent monitoring with the goal of detecting a recurrence when stones are small enough to remove by urinary catheter or by voiding urohydropropulsion.

- The following frequency of rechecks is recommended:

› q 2 months for 1 year; if no recurrence, then

› q 4 months for an additional year; if no recurrence, then

› q 6 months thereafter.

- At each recheck, evaluate a lateral abdominal radiograph and a urinalysis.

- If at any time the dog has a recurrence, perform voiding urohydropropulsion and then go back to the beginning of the recheck protocol

Newsletter

From exam room tips to practice management insights, get trusted veterinary news delivered straight to your inbox—subscribe to dvm360.