Causes, incidence, treatment of pulmonary and systemic fungal infections in horses

Pulmonary or systemic fungal infections in horses historically have resulted in a high mortality rate.

Pulmonary or systemic fungal infections in horses historically have resulted in a high mortality rate. However, with earlier diagnosis and the increasing availability of affordable anti-fungals with known pharmacokinetic profiles, successful outcomes are becoming more common.

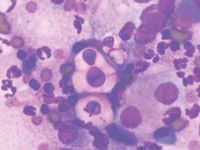

Photo 1: Photomicrograph of an impression smear from a biopsy of a mass in the nasal passage of a horse with chronic serosanguinous nasal discharge and dyspnea.

Systemic fungal infections have an insidious progression, often presenting with non-specific clinical signs. A thorough clinical evaluation usually is required to confirm diagnosis.

For pulmonary infections, thoracic radiography and collection of fluid samples by tracheal wash or broncho-alveolar lavage are useful. Cytologic or histologic examination of lesions may identify morphologic features of fungal organisms. The etiologic agent can be definitively identified by microbiologic culture, immunohistochemistry or polymerase chain reaction.

Photo 2: Radiograph of a horse with a history of chronic serosanguinous nasal discharge and dyspnea. Dorsoventral radiograph of the skull demonstrates significant increase in soft-tissue opacity within the nasal cavity and right maxillary sinus due to cryptococcal infection.

Treatment options depend on the site and extent of the infection, accessibility to surgical intervention, the etiological agent, the known antifungal susceptibilities, evidence-based study from human medicine and financial resources of the owner.

Fungi are eukaryotic organisms with a definitive cell wall made up of chitins, glucans and mannans. Within the cell wall, the plasma membrane contains ergosterol, a cell membrane constituent frequently targeted by anti-fungal agents.

Pathogenic fungi can be divided into three groups: multinucleate septate filamentous fungi; non-septate filamentous fungi; and yeasts.

Dimorphic fungi can change between forms, depending on environmental conditions.

In soil and decaying matter, the mycelial form usually is present and is composed of a collection of hyphea. The mycelia produce infective spores that can inoculate vertebrate tissue.

Pulmonary fungal infections in horses can cause pulmonary granulomas, diffuse pneumonia or pleuropneumonia. Mycotic granulomas of the upper respiratory tract have been found in the nasal passages, paranasal sinuses, nasopharynx, guttural pouch and trachea of infected horses.

Pulmonary-affected horses can present with signs similar to those of bacterial pneumonia and, if the condition is chronic, weight loss.

Photo 3: A 12-year-old Quarter Horse mare presented with dyspnea and a three-week history of a serosanguinous nasal discharge. Conidiobolomycosis was diagnosed by culture and histology from a biopsy taken under endoscopic guidance of the mass.

The most common clinical signs of upper respiratory fungal infection include unilateral or bilateral serosanguineous or mucopurulent nasal discharge as well as inspiratory and expiratory noise.

Other clinical signs include facial deformation and dyspnea caused by partial blockage of nasal passages by granulomatous masses.

Fungal pneumonia sometimes affects horses that are immunocompromised or neutropenic or that have enteritis/colitis, bacterial pneumonia or neoplasia. Systemic infections can have variable clinical signs depending on the location and extent of the infection. Fungal infections can affect multiple organs and body cavities.

Weight loss, colic and diarrhea often occur with infection within the abdominal cavity. Immunodeficiency, congenital or acquired, or glucocorticoid therapy may predispose a horse to fungal infection.

Fungal infections

CONIDIOBOLOMYCOSIS: Conidiobolus coronatus is a saprophytic fungus that generally infects the mucous membranes and causes single to numerous granulomatous lesions of the upper respiratory tract (i.e., nasal passages, trachea or soft palate) in horses.

CRYPTOCOCCOSIS: This infection is commonly caused by Cryptococcus neoformans and C. gattii, which are ubiquitous, saprophytic, round, basidiomycetous yeast-like fungi with a large heteropolysaccharide capsule that does not take up common cytologic stains.

Equine cryptococcosis is relatively common in western Australia, and there is an epidemiologic relationship between C. gattii and the Australian river red gum tree and between C. neoformans var neoformans and bird (particularly pigeon) excreta.

Cytologic or histopathologic identification is very reliable for diagnosis because of the characteristic morphology. There are isolated published cases of Cryptococcus in horses and other species (especially cats) throughout the United States, with a recent epidemic reported in western Canada.

Cryptococcosis in horses is associated primarily with pneumonia, rhinitis, meningitis and abortion. However, successful medical treatment has until recently rarely been reported. Over the last 12 months case reports of successful treatment in horses have come from the Universities of Tennessee, Georgia and Auburn.

ASPERGILLOSIS: In horses, this infection has a propensity for vascular invasion. A definitive diagnosis can be made by culture or staining by immunohistochemistry or immuno-fluorescence. Aspergillus spp. are very common in the environment, especially in moldy feed and bedding. They are opportunistic pathogens, and often cause disease in horses that are immunosuppressed from debilitating conditions such as enterocolitis, septi-cemia, neoplasia, Cushing's disease, equine protozoal myeloencephalitis or major surgery, or that have been treated with immunosuppressive drugs.

Infection occurs by inhalation of an overwhelming number of spores or by translocation of organisms across an inflamed gastrointestinal tract.

Aspergillosis pneumonia is almost always fatal, often with mild or no signs. The two forms of Aspergillosis pneumonia reflect the two portals of entry, with fungal proliferation and invasion of the small airways occurring secondary to inhalation, and angioinvasive aspergillosis with lesions centered around large blood vessels likely due to hematogenous infection originating from the gastrointestinal tract.

Pulmonary aspergillosis is characterized grossly by multiple nodules throughout the lungs. On histologic examination, there is often necrosis and purulent inflammation. Necrosis is due to toxin and enzyme production as well as vascular obstruction. Fungal invasion of blood vessels is common and results in vasculitis, thrombosis, infarction and necrosis.

Aspergillosis is prevalent throughout the United States; however, most causes of nasal mycosis in Europe are caused by aspergillosis.

GUTTURAL POUCH MYCOSIS: Mycotic infection of the guttural pouch generally occurs on the dorsal wall of the medial compartment or on the lateral wall of the lateral compartment.

Mycotic plaques typically are located over the internal carotid artery (less common over the external or maxillary artery, which may result in fatal hemorrhage).

Plaques can vary in size and can expand to cover the entire roof of the pouch and may erode through the median septum into the neighboring pouch.

Horses generally have intermittent mucopurulent to serosanguineous nasal discharge or epistaxis. Without proper treatment, secondary neurologic abnormalities may result if cranial nerves IX, X, XI or XII, which traverse the guttural pouch, are affected. This commonly results in dysphagia.

Although fungal infection generally is more common in the southern United States, most cases of guttural pouch mycosis are reported in the North.

BLASTOMYCOSIS: This is caused by inhalation of conidia of the thermally dimorphic saprophytic fungus Blastomyces dermatitidis. Blastomyces yeasts can be identified on cytologic examination, often within multinucleated giant cells.

Blastomycosis reportedly was caused by pulmonary abscessation, pyogranulomatous pneumonia, pleuritis, peritonitis, and abscesses in a 5-year-old horse.

It is endemic in the Mississippi, Missouri and Ohio River watersheds, the St. Lawrence River Valley and the Great Lakes regions of Canada and the United States.

HISTOPLASMOSIS: This infection is caused by the saprophytic, dimorphic fungus Histoplasma capsulatum and is most prevalent in moist soil containing bird or bat waste. H. capsulatum may occur in an enteric, a pulmonary or a disseminated form.

Histoplasmosis has been reported infrequently in horses, but it is the most common endemic mycosis of humans. It is endemic in areas similar to blastomycosis. Epidemics have occurred secondary to exposure to pigeon houses, or during excavation of old barns or houses. Clinical disease is more common in immunocompromised hosts.

COCCIDIOIDOMYCOSIS: This is a systemic fungal infection caused by Coccidioides immitis, a soil saprophyte that grows in areas with sandy, alkaline soils and semi-arid conditions.

In the environment, C. immitis exists as a mycelium with thick-walled, barrel-shaped arthroconidia. Inhalation of airborne arthroconidia can result in infection. These organisms can enlarge to form nonbudding spherules, which incite an inflammatory reaction in the lungs and lymph nodes.

Affected horses can experience weight loss, fever, abdominal pain and signs of respiratory disease. Localized, recurring nasal granulomas also have been reported. Diffuse infections with granulomas in the lungs, liver, kidneys or spleen have a grave prognosis. It is a disease seen primarily in the Southwest.

SCOPULARIOPSIS: This is a very rare fungal infection, but was diagnosed in a 2-year-old filly with Scopulariopsis pneumonia by culture of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. The filly had extensive granulomatous lesions with the pulmonary parenchyma and pleural effusion visible on thorasic ultrasonography.

ADIASPIROMYCOSIS: Also quite rare in the United States, adiaspiriomycosis is not isolated to any specific area/climate/region.

A horse was diagnosed by percutaneous lung biopsy with adiaspiromycosis miliary fungal pneumonia caused by the saprophytic soil mold Emmonsia crescens.

CANDIDIASIS: Systemic candidiasis was diagnosed and successfully treated in four neonatal foals. Each had prior sepsis attributable to Gram-negative bacteria that had been aggressively treated with numerous antibiotics and parenteral nutrition. Candida albicans was cultured from a transtracheal wash from one of the foals. Three had Candida glossitis, and one had panophthalmitis and fungal keratitis. The infection is ubiquitous around the country.

PNEUMOCYSTOSIS: Pneumocystis carinii has been reclassified from a protozoan to a saphrophytic fungus based on DNA sequence of its 16S-like RNA subunit. Some researchers even consider it a plant because it lacks ergosterol, the major fungal sterol. It exists as an ameboid yeast or as a cystic sporangia. Pneumocystis carinii cannot be cultured, and diagnosis is based on the cytological identification of characteristic morphologic features using specimens obtained by bronchoalveolar lavage rather than tracheal wash. P. carinii causes diffuse interstitial pneumonia, especially in immunocompromised horses such as Arabian foals with severe combined immunodeficiency.

Treatment advances

Over the last few years results of pharmacokinetic studies have been published, providing practitioners with appropriate dosages and body-fluid concentrations for fluconazole, itraconazole and voriconazole.

Although fluconazole does not have good activity against Aspergillis spp., successful therapy with fluconazole has been reported in horses suffering from mycotic infections caused by Cryptococcus, conidiobolomycosis and Coccidioides.

Fluconazole also is effective against Histoplasma and Blastomyces.

Voriconazole is effective against all these organisms, in addition to Aspergillus, but the cost of treatment is likely to remain prohibitive for years.

Kane is a Seattle author, researcher and consultant in animal nutrition, physiology and veterinary medicine, with a background in horses, pets and livestock.

Stewart is an associate professor of equine internal medicine at the Auburn University College of Veterinary Medicine.