Clinical Exposures: Type III hiatal hernia in a Shar-Pei

This case report describes the clinical signs and surgical treatment of an unusual hiatal hernia in a Chinese Shar-Pei.

An 8-year-old 29-kg intact male Shar-Pei was presented for evaluation of acute respiratory distress and vomiting of one day's duration. No history of trauma was recorded.

Diagnostic tests

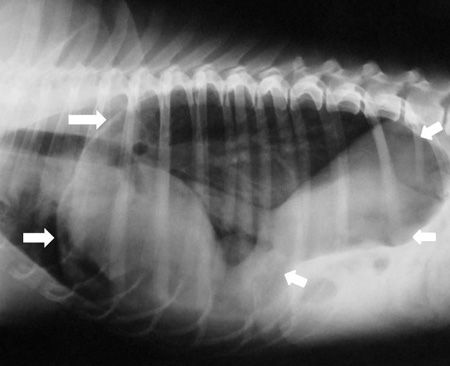

A physical examination revealed that the dog was in good body condition and mildly dyspneic. Complete blood count and serum chemistry profile results were normal. On thoracic radiography, a gas-filled stomach in the thoracic cavity, overlying the diaphragmatic margin, was observed (Figure 1). Hiatal hernia was diagnosed.

1. A lateral radiograph of the thorax and cranial abdomen of an 8-year-old Shar-Pei. A compartmentalized gas-filled structure (arrows) is seen in the middle and caudal thorax. Ill-defined soft tissue opacity prevents the clear appearance of the cardiac apex and cupula. The stomach is not evident in the cranial abdomen.Fluids and anesthesia

The dog was treated with lactated Ringer's solution (20 ml/kg intravenously) for 30 minutes. After initial stabilization, the dog was given acepromazine (0.02 mg/kg intravenously) and a bolus of fentanyl (2 μg/kg intravenously) before induction with propofol (2 mg/kg intravenously to effect) to allow for tracheal intubation. The dog was also given robenacoxib (Onsior-Novartis Animal Health; 1 mg/kg subcutaneously). General anesthesia was maintained with inhaled isoflurane in oxygen under intermittent positive pressure ventilation.

During surgery, a constant-rate infusion of fentanyl (0.05 μg/kg/min) and lactated Ringer's solution (10 ml/kg/hr) were administered. The patient was continuously monitored, including electrocardiography, capnography, pulse oximetry and blood pressure measurements.

Surgery

A ventral midline celiotomy was made. Abdominal exploration revealed that the dog's entire stomach protruded into the thoracic cavity through the esophageal hiatus. The stomach was reduced by gentle traction. The phrenoesophageal ligament was found to be lax. Further inspection revealed a 5-cm defect in the adjacent tendinous site of the diaphragm. The defect was located in the right lateral margin of the esophageal hiatus (Figure 2).

2. Intraoperative view of the esophageal hiatus after a midline celiotomy. An enlarged hiatus with a redundant phrenoesophageal ligament (white arrows) and a diaphragmatic defect in the adjacent right tendinous site of the diaphragm grasped with Allis tissue forceps is visualized.The esophageal hiatus was closed with two layers of simple interrupted 2-0 polypropylene sutures. Esophagopexy was performed by placing two simple interrupted sutures of the same suture material on each side of the hiatus between the diaphragm and the muscular layer of the ventral esophagus but avoiding the vagus nerves. A left-sided 4-cm-long fundic incisional gastropexy was performed with 0 polypropylene suture in a continuous pattern. Before abdominal closure, air from the pleural space was evacuated with a butterfly needle through the dog's diaphragm.

The dog's postoperative recovery was uneventful, and morphine (0.1 mg/kg intramuscularly every four hours for 1.5 days) was administered to provide analgesia. The dog was fed canned food 12 hours after surgery, had a good appetite and was discharged from the hospital two days after surgery with oral meloxicam (0.1 mg/kg once a day) for three days. The dog was presented for evaluation 20 days after surgery completely free of clinical signs. The thoracic radiographs obtained postoperatively confirmed the normal anatomic position of the stomach and an intact diaphragm. According to the owner via a telephone call 18 months after surgery, the dog was free of respiratory or gastrointestinal signs.

Discussion

Hiatal hernia is the protrusion of abdominal contents into the thoracic cavity through the esophageal hiatus of the diaphragm.1 Hiatal hernia occurs uncommonly in small animals and is classified into four types.1-3

Type I, sliding hiatal hernia, is the most commonly encountered hernia. With this type, the gastroesophageal junction and part of the stomach move intermittently into the thoracic cavity through the esophageal hiatus of the diaphragm.4-10

Type II, paraesophageal hernia, occurs when the gastroesophageal junction remains in its normal position and part of the stomach is displaced into the thoracic cavity through the esophageal hiatus. This type of hernia is reported sporadically in dogs.11-14

Type III, mixed hiatal hernia, is a combination of sliding and paraesophageal hernias. Type III hernias are rare in dogs.15-18

In type IV hiatal hernia, abdominal contents other than the stomach are herniated into the thoracic cavity through the esophageal hiatus. Type IV hernias are rare in dogs.15-18

Congenital or acquired

Hiatal hernia may be congenital or acquired. Chinese Shar-Peis seem to have a congenital predisposition with a partially heritable trait in developing type I hiatal hernia.4,5,8,10 An anatomic abnormality of the esophageal hiatus in this breed may be responsible for an axial separation between the lower esophageal sphincter and the diaphragm.8,10 Acquired hiatal hernia can be related to a traumatic incident, a diaphragmatic hernia, or an upper respiratory obstruction.6,7,9,19,20 Age-related degeneration of the phrenoesophageal ligament was reported in people but not in dogs.2,21

In this case, no history of trauma was reported and no clinical signs of trauma were detected on physical examination. The type III hiatal hernia reported in this case may be a congenital one despite the dog's advanced age. A pre-existing asymptomatic hiatal hernia that was exacerbated by an acute rupture of a congenitally weakened site of the diaphragm resulting in gastric protrusion into the thoracic cavity constituting a type III hiatal hernia may be a possible explanation of the pathophysiology of this dog's hiatal hernia.7,18 To our knowledge, this case is the first type III hiatal hernia reported in a Shar-Pei.

Clinical signs

Clinical signs are usually chronic and include regurgitation, vomiting, hypersalivation, hematemesis, weight loss and respiratory distress. In animals with type I hiatal hernia, the clinical signs are often associated with gastroesophageal reflux or aspiration pneumonia. However, some animals with type I hiatal hernia do not exhibit clinical signs. In this case, acute respiratory distress was reported because of lung compression by the stomach, which had protruded into the thoracic cavity resulting in gastric distension.

Diagnostic imaging

Hiatal hernia is diagnosed based on the results of plain radiography or contrast esophagography.4-10 Contrast esophagography may help distinguish between type I and II hernias and other soft tissue masses in the caudal mediastinum. Differential diagnoses include megaesophagus, esophageal epiphrenic diverticulum, gastroesophageal intussusception, esophageal masses and an esophageal foreign body.

In this case, plain radiography was sufficient to diagnose hiatal hernia. A contrast study was not necessary since type I hiatal hernia was not suspected. Furthermore, the condition of the animal precluded the performance of a contrast study.

Treatment

Type I hiatal hernia may be treated medically or surgically. However, some authors are in favor of surgery as the treatment of choice for Shar-Peis with type I hiatal hernias because they tend not to respond to medical treatment.8,10,22 Dogs with types II, III and IV hiatal hernias require surgical treatment.2 In cases of acute respiratory distress, adequate cardiorespiratory stabilization is achieved through the emergency decompression of the stomach by passage of an orogastric tube or insertion of a hypodermic needle through the left chest wall into the stomach. This was not done in this case because the dog was mildly dyspneic.

In this case, the acute condition of the dog with a diagnosis of hiatal hernia other than type I warranted surgical repair of the esophageal hiatus.

This case report indicates that type III hiatal hernia should be included in the differential diagnoses of hiatal hernias in Shar-Peis.

Emmanouil Tzimtzimis, DVM, MS, MRCVS

Georgios Kazakos, DVM, PhD

Michail Patsikas, DVM, PhD, DECVDI

Matina Giannikaki, DVM, MS

Lysimachos G. Papazoglou, DVM, PhD, MRCVS

Department of Clinical Sciences

School of Veterinary Medicine

Aristotle University of Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki, Greece

References

1. Katsianou I, Svoronou M, Papazoglou LG. Current views regarding hiatal hernia in dogs and cats. Hell J Compan Anim Med 2014;3:31-39.

2. Sivacolundhu RK, Read RA, Marchevsky AM. Hiatal hernia controversies-a review of pathophysiology and treatment options. Aust Vet J 2002;80:48-53.

3. Bright R. Hiatal hernia. In: Monnet E, ed. Small animal soft tissue surgery. Ames, Iowa: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013:321-327.

4. Ellison GW, Lewis DD, Phillips L, et al. Esophageal hiatal hernia in small animals: literature review and a modified surgical technique. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 1986;23:391-399.

5. Prymak C, Saunders HM, Washabau RJ. Hiatal hernia repair by restoration and stabilization of normal anatomy. An evaluation in four dogs and one cat. Vet Surg 1989;18:386-391.

6. Bright RM, Sackman JE, DeNovo C, et al. Hiatal hernia in the dog and cat: a retrospective study of 16 cases. J Small Anim Pract 1990;31:244-250.

7. Lorinson D, Bright RM. Long-term outcome of medical and surgical treatment of hiatal hernias in dogs and cats: 27 cases (1978-1996). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1998;213:381-384.

8. Callan MB, Washabau RJ, Saunders HM, et al . Congenital esophageal hiatal hernia in the Chinese shar-pei dog. J Vet Intern Med 1993;7:210-215.

9. Hardie EM, Ramirez O, Clary EM, et al. Abnormalities of the thoracic bellows: stress fractures of the ribs and hiatal hernia. J Vet Intern Med 1998;12:279-287.

10. Guiot LP, Lansdowne JL, Rouppert P, et al. Hiatal hernia in the dog: a clinical report of four Chinese shar peis. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2008;44:335-341.

11. Teunissen GH, Happe RP, Van Toorenburg J, et al. Esophageal hiatal hernia. Case report of a dog and a cheetah. Tijdschr Diergeneeskd 1978;103:742-749.

12. Miles KG, Pope ER, Jergens AE. Paraesophageal hiatal hernia and pyloric obstruction in a dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1988;193:1437-1439.

13. Kirkby KA, Bright RM, Owen HD. Paraoesophageal hiatal hernia and megaoesophagus in a three-week-old Alaskan malamute. J Small Anim Pract 2005;46:402-405.

14. Aslanian ME, Sharp CR, Garneau MS. Gastric dilatation and volvulus in a brachycephalic dog with hiatal hernia. J Small Anim Pract 2014;55:535-537.

15. Williams JM. Hiatal hernia in a Shar-Pei. J Small Anim Pract 1990;31:251-254.

16. Auger JM, Riley SM. Combined hiatal and pleuroperitoneal hernia in a shar-pei. Can Vet J 1997;38:640-642.

17. Rahal SC, Mamprim MJ, Muniz LM, et al. Type-4 esophageal hiatal hernia in a Chinese Shar-pei dog. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 2003;44:646-647.

18. Gordon LC, Friend EJ, Hamilton MH. Hemorrhagic pleural effusion secondary to an unusual type III hiatal hernia in a 4-year-old Great Dane. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2010;46:336-340.

19. Pratschke KM, Hughes JM, Skelly C, et al. Hiatal herniation as a complication of chronic diaphragmatic herniation. J Small Anim Pract 1998;39:33-38.

20. Lecoindre P, Richard S. Digestive disorders associated with the chronic obstructive respiratory syndrome of brachycephalic dogs: 30 cases (1999-2001). Rev Med Vet 2004;155:141-146.

21. Christensen J, Miftakhov R. Hiatus hernia: a review of evidence for its origin in esophageal longitudinal muscle dysfunction. Am J Med 2000;108:Suppl 4a:3s-7s.

22. Holt D, Callan MB, Washabau RJ, et al. Medical treatment versus surgery for hiatal hernias. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1998;213:800.