- dvm360 May 2022

- Volume 53

- Issue 5

- Pages: 52

Hospital design for treating patients with cancer: USP Regulations

Learn key hospital design protocols to help protect patients and staff

Content submitted by Animal Arts, a dvm360® Strategic Alliance Partner

Over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, veterinary professionals have had a lot to worry about. How to keep ourselves and our loved ones safe was at the top of the list. We were forced to take a closer look at how disease can be transmitted and what it’s like to do everything we can to keep each other safe. This included our pets. Many people adopted pets during the pandemic and others just spent much more time with them at home than they had before. Consequently, our veterinary teams were busier than ever on the front lines diagnosing, treating, and caring for our 4-legged family members.

Before the pandemic for non–health care workers, I probably would have needed to define what PPE stood for. Now, it’s common terminology. We now think about how we touch things and how we can potentially pass disease, unknowingly, to someone else. We even think about how long we wash our hands. When thinking about designing safer spaces for our veterinary teams, we have learned that they need more space; touchless faucets where operationally functional; nonporous, easily cleanable surfaces; and well-planned spaces for proper storage and proper placement of equipment to facilitate a safe working environment. Many of the best practices for safety in hospital design that we all instinctually knew about prepandemic have come flooding back.

Right as the pandemic was getting started, I was patiently waiting for the appeal process for the United States Pharmacopeial Convention’s (USP) revised 2019 General Chapters, <795> Pharmaceutical Compounding – Nonsterile Preparations and <797> Pharmaceutical Compounding – Sterile Preparations, to be complete so we could better understand their implications for designing the safest veterinary oncology area that we could for our clients. Early in January 2020, I published an article in dvm360® titled “Handle hazardous drugs? Read this” that provided the general background and importance of these 2 chapters along with their counterpart, General Chapter <800> Hazardous Drugs – Handling in Healthcare Settings.1 For over a year before that, we had begun implementing the new standards in our designs. Then, on March 12, 2020, as we were all rightfully concentrating on this new thing called COVID-19, USP issued a decision on appeal of the revised General Chapters <795> and <797>.

The decision was to grant appeals for these 2 General Chapters and to remand the chapters to the Compounding Expert Committee (CMP EC) with the recommendation for further engagement on the issues raised concerning the beyond-use date provisions.2 The CMP EC is still in review and, as such, the last revised chapters remain official. The kicker here is that until the 2019 versions of these General Chapters are adopted, USP <800> is not compendially applicable. One reason for this is that a General Chapter numbered below 1000 becomes compendially applicable, and a required standard, when the chapter is referenced in another General Chapter below 1000.

Without the revised <795> and <797> chapters, General Chapter <800> holds no regulatory weight. This chapter was devised to create a public standard aimed at minimizing the potential risk of exposure and the information in it is crucial for the safety of both the people administering the drugs and the patients who receive them.3

It has been 2 years since the start of the pandemic and since the CMP EC began its review. The comment period officially closed March 17, 2022, and it is expected that as early as the beginning of next year, we will see the revisions become effective. We need to continue to focus on using this time to begin implementation of the standards.

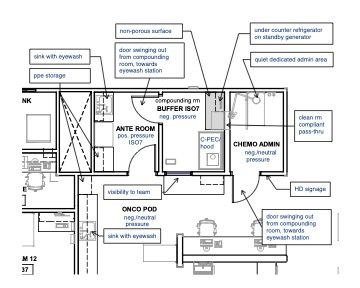

Tracing the path of hazardous drugs (HDs) from the moment they arrive at the hospital into your receiving area, to your oncology department, and then to a client or administered to a pet is critical. Breaking this down a little further to help you understand the flow, we have illustrated the process in Figure 1. The boxes in orange are the areas your architects should design with your input. The gray boxes are the areas that the veterinary team members handling these drugs will be responsible for.

Let’s take a quick look at some highlights of these 3 General Chapters:

- All antineoplastic drugs requiring manipulation must follow all containment requirements.

- Engineering controls are required. These controls are containment primary engineering control (C-PEC an example being the hood itself), containment secondary engineering control (C-SEC) such as the room in which the C-PEC/hood is located), and supplementary levels of control.

- Sterile and nonsterile hazardous drugs (HDs) must be compounded within a C-PEC located in a C-SEC.

- For sterile preparations, the C-PEC must be in a C-SEC, which may either be an unclassified containment segregated compounding area (C-SCA) or an ISO Class 7 buffer room with an ISO Class 7 anteroom. These setups are illustrated in the following plan examples.

- If the C-PEC is placed in a C-SCA, the beyond-use date (BUD) of all compounded sterile preparations must be limited as described in <797> for CSPs prepared in segregated compounding areas. (In <797>, depending upon which version you are referencing, you will need to confirm that you will be able to operationally comply with the low- or medium-risk level or Category 1.)

- Volatile drugs can be compounded in a Type 2, Class II BSC. If you plan to use a CACI, you will need to verify with the hood manufacturer for compliance.

Keep in mind that oncology departments require much more than spaces to handle chemotherapy drugs. They need functional exam space, sufficient nursing, charting spaces, and sufficient additional treatment areas for nonchemo administration. Each full-time–equivalent doctor, if space allows, should have 2 exam rooms, a treatment table, and 2 nurse charting stations dedicated to their service. Additionally, there should be animal housing to accommodate the larger physical size of most oncology patients, as well as varying housing types and locations to support the needs of the patients and procedures that are carried out.

In the floor plan example below (Figure 4) there is a run ward nearby as well as cages within the treatment room. Surrounding services should also help support oncology by providing a flex space for additional treatment tables and animal housing. Because many of the animals that are in this area of the hospital are immunocompromised, you also want to minimize cross traffic of other patients and people and keep the service close to the exam rooms and front desk team for easier support and transport of animals.

Final thoughts

As veterinary medicine continues to advance and provide more oncology services to more patients, it’s essential that we design to incorporate the goals of these 3 significant USP General Chapters as part of our recognition and support of the safety and facility needs of the people who work and pets that are cared for in these spaces.

References

- Pollard V. Handle hazardous drugs? Read this. dvm360. January 7, 2020. Accessed March 31, 2022.

https://www.dvm360.com/view/handle-hazardous-drugs-read-this - Appeals panel decisions on USP <795>, <797>, and <825>. USP. March 12, 2020. Accessed March 31, 2022.

https://www.usp.org/sites/default/files/usp/document/our-work/compounding/decisions-appeals-fs.pdf - Role and applicability of USP General Chapter <800> related to safe handling of hazardous drugs. USP. March 12, 2020. Accessed March 31, 2022.

https://www.usp.org/sites/default/files/usp/document/our-work/compounding/compendial-applicability-of-usp-800.pdf

Articles in this issue

over 3 years ago

The impact of Fear Freeover 3 years ago

The secret to happy clientsover 3 years ago

An encouraging phone call and a flopping horseover 3 years ago

Euthanasia attendants in modern practiceover 3 years ago

Lyme disease risk forecast to increaseover 3 years ago

Maximizing adherence to minimize heartworm resistanceover 3 years ago

A closer look at hydrotherapy for rehabilitationover 3 years ago

Why a blood smear evaluation should be performed with every CBCNewsletter

From exam room tips to practice management insights, get trusted veterinary news delivered straight to your inbox—subscribe to dvm360.