Hot Literature: Bartonellosis: What do we know? What can we do?

More and more, veterinarians are being asked to answer questions regarding potentially zoonotic diseases. When it comes to bartonellosis, the answers can be particularly tough to formulate because of the disease?s frequently vague or absent clinical signs and the difficulty in identifying and controlling the infection.

More and more, veterinarians are being asked to answer questions regarding potentially zoonotic diseases. When it comes to bartonellosis, the answers can be particularly tough to formulate because of the disease’s frequently vague or absent clinical signs and the difficulty in identifying and controlling the infection. Recent articles outlining the pathogenesis and zoonotic potential of Bartonella species aim to give veterinary practitioners the most recent information regarding these elusive bacteria. Bartonellosis in cats, dogs, and people was recently reviewed by different research groups in Veterinary Microbiology, the Journal of Applied Microbiology, and the Journal of Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care.

TRANSMISSION

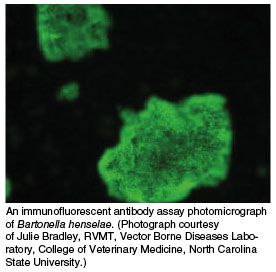

Many species of these small, gram-negative bacteria exist, and a large number of arthropods are confirmed or potential vectors for transmission of these bacteria among animals. The function of Bartonella species as a cause of disease in domestic animals and people is still being investigated. Cats are a primary reservoir for the important zoonotic species Bartonella henselae and Bartonella koehlerae, as well as other Bartonella species. However, new information confirms that dogs, rodents, and many other hosts are also reservoirs for the various Bartonella species, which makes informing clients about this potential source of disease important. Arthropod vectors, including, fleas, ticks, and biting flies, may transmit the bacteria, which then localize to erythrocytes and endothelial cells. From there, the bacteria can cause infection in various tissues or organs. Additionally, cats and dogs can be infected with more than one Bartonella species, further complicating diagnosis. Prevalence of B. henselae, the main agent responsible for cat scratch disease in people, is largely dependent on climate, increasing with temperature and humidity. Cats less than 1 year of age and those that are strays are most likely to be carriers of the bacteria.

In cats, fleas are responsible for transmitting the most common zoonotic Bartonella species. Chronic recurring bacteremia is common in cats, which makes identification and control difficult. Experimentally, cats have been infected by flea excrement injected intradermally, similar to human bartonellosis contracted from contaminated cat scratches or bites. And infected cat blood has also proved to be a means of transmission between cats when injected intramuscularly or intravenously. However, in flea-free environments, transmission of infection between individuals has not been noted, and, in dogs and cats, natural disease appears to require an arthropod vector. Ticks are another likely vector in cats, dogs, people, and other mammals. Relapsing bacteremia is common, and infected individuals do not appear to gain significant immune protection after infection. This lack of subsequent immunity may partly be due to the wide variety of Bartonella species and subspecies since cross-protection has not been shown to occur. Also, Bartonella species bacteria tend to localize within erythrocytes and other cells that are isolated from both natural immune response and antibiotics.

CLINICAL SIGNS

Cats and dogs infrequently show clinical signs of bartonellosis bacteremia. If signs are present, they may be subtle and often go unnoticed by owners. When signs are documented, they most frequently include mild fever, uveitis, endocarditis, and, in some cases, myocarditis. Bartonella species have been cultured from various tissues, effusions, and transudates in sick animals; however, the role of the bacteria in disease is unclear. Additionally, bacteremic cats have been observed to have transient disease following stress such as after a surgical procedure. Bartonella species infections may also contribute to immunosuppression, predisposing patients to other infections. Experimentally infected cats have shown transient lymphadenopathies, fevers, and mild neurologic signs.

Less data is available in dogs. However, in dogs, bartonellosis has been associated most consistently with endocarditis, especially in large-breed dogs.

In people, the most common zoonotic infection is cat scratch disease, which is marked by the development of a pustule at the site of inoculation about seven to 12 days after a cat scratch and lasting about one to three weeks. This is often followed by a low-grade fever and enlargement of a regional lymph node. These signs can last for weeks to months. More generalized or systemic signs are less common but can occur.

DIAGNOSIS

Diagnosis of Bartonella species infection is challenging, and veterinarians are likely to be asked to screen healthy pets when owners are themselves infected or when someone in the household is immunocompromised. In cats, blood cultures are the most reliable method for detecting bacteremia. This is not fool-proof, however, since the bacteremia tends to be relapsing. Blood cultures are indicated in sick cats with a suspicious history and clinical signs or if a client’s physician requests testing. In dogs, bartonellosis should always be considered in cases of endocarditis and granulomatous disease.

Serologic testing is not without limitations and has been proved to be highly insensitive in dogs and people. In cats, frequent false negative results make this an unreliable tool to rule out Bartonella species infection. Standard PCR testing has also been used.

A newer diagnostic approach involving enrichment culture of Bartonella species from blood or other fluids and tissues (BAPGM—Galaxy Diagnostics) followed by PCR testing is showing improved diagnostic efficacy.

TREATMENT

How do you treat this bacteremia? No specific guidelines have been adopted, but treating healthy animals is not recommended. Antibiotics such as enrofloxacin, doxycycline, erythromycin, amoxicillin, and tetracycline have been tried; however, further study is needed to determine their efficacy against various Bartonella species in infected animals. Azithromycin has been suggested for its intracellular activity, but again, there has not been sufficient data or testing to determine its effectiveness in these cases. In all cases, a long course of antibiotic therapy is necessary (four to six weeks), not only to eliminate the infection, but to reduce the risk of developing resistant bacteria. Diagnosis and treatment are further complicated in dogs by the fact that sick dogs with known tick exposure may be coinfected with other vector-borne diseases such as Rocky Mountain spotted fever, ehrilichiosis, babesiosis, or other rickettsial infections.

PREVENTION

Prevention is an important area to focus on, and this is where veterinarians can play a vital role. Do not transfuse blood from seropositive or culture-positive individuals, and encourage clients to avoid exposure to infected animals and arthropod vectors. Veterinarians are at high risk of extensive exposure to bacteremic animals, arthropod vectors (e.g. fleas, ticks), and potentially infected tissues and fluids. Children and people in contact with younger cats or those with large flea infestations are also at higher risk of infection. Avoiding needle sticks, washing hands and wounds thoroughly, and handling potentially infected tissues, effusions, and other patient samples with appropriate care can help prevent infection.

ZOONOTIC POTENTIAL

Several Bartonella species are potentially zoonotic and can cause a range of clinical syndromes in people besides cat scratch disease, including encephalopathies in children; relapsing fevers with bacteremia; endocarditis; optic neuritis; pulmonary, hepatic, and splenic granulomas; and many others. Localized infections are more common, but systemic disease is likely in immunocompromised individuals. Depending on the Bartonella species, people can be infected by inoculation with flea excrement from cat or dog scratches and bites, or directly by arthropod vectors. Inform clients about these bacteria, how they are transmitted, and especially about their association with flea or tick infestations. Encourage clients to provide flea and tick control for their pets, avoid activities likely to result in bites or scratches, wash any wounds thoroughly, and seek medical attention when necessary.

SUMMARY

Bartonellosis is a serious zoonotic concern. These recent articles review the disease and provide vital information regarding Bartonella bacteria. They also identify the need for further study to better understand, diagnose, and treat this stealth pathogen.

Guptill L. Bartonellosis. Vet Microbiol 2010;140(3-4):347–359.