Owning It: The Power of Admitting Your Mistakes

By disclosing clinical mistakes and dealing with the consequences and emotions that result, veterinary professionals can gain greater resilience and reduce burnout and depression.

The prevalence of medical mistakes resulting in harm to patients is high. In fact, each year more than 250,000 deaths in U.S. hospitals are attributed to medical errors.1 If this figure included diagnostic errors, the number of prevent- able deaths would rise to approximately 400,000 annually.2 Related surveys on the topic have also revealed that 83 to 92 percent of physicians have made a mistake in their career that resulted in a near miss (NM), adverse event or serious error.3,4 Most recently, a 2018 survey study from the Veterinary Information Network (VIN) found that 74 percent of veterinarians had been involved in at least one NM or harmful medical error within the previous year.5

Nearly all veterinarians know what it feels like to make an unfortunate error. After all, we’re human. Take some comfort in knowing that you’re not alone, but also recognize that there are steps you can take to significantly decrease the lasting ramifications of medical errors for your patients, your clients and you.

RELATED:

- Disclosing Medical Errors with the TEAM Model

- Disclosing Medical Errors

The Personal Fallout From Medical Errors

While many more studies have been published on the impact of medical errors on human health care providers, the effects are similar, if not identical, for veterinary professionals. The emotional impact on these individuals — who are considered secondary victims — is remarkable.6 Even though both human and veterinary health care professionals understand intellectually that serious mistakes happen, they routinely believe that errors can be prevented if correct procedures are followed. It should come as no surprise, then, that health care workers involved with a medical error or NM feel:

- Puzzled and shocked

- Fearful of discipline, litigation and loss of reputation

- Guilty and angry at themselves

- Anxious in general or specifically about making future errors

- Distressed

- Less satisfied with their jobs

- Less confident in their abilities

- Burned out

In my experience dealing with these emotions following a medical mistake, the symptoms are worse when I keep the error to myself. I’ve found that discussing my feelings provides quite a bit of relief, so I purposefully maintain a group of fellow practitioners on whom I can call in times of need.

Even if you don’t currently have a close-knit group you can turn to, a number of industry-wide outlets have been established to help combat the guilt and distress associated with making medical errors:

- VIN’s Venting Over a Venti is an online forum that provides members with an outlet to discuss their experiences and share ideas.

- Not One More Vet is a Facebook forum where veterinarians can solicit feedback anonymously from colleagues, which can be especially beneficial while the event is unfolding.

- The Veterinary Confessionals Project is a website that allows users to submit career-related thoughts and secrets on any topic.

Dilemmas Related to Disclosure

Social psychologist Christina Maslach, PhD, who is well known for her research on occupational burnout, famously identified six areas of mismatch between people and their jobs that lead to burnout.7 Three of these — lack of control, absence of fairness and conflict in values — may be triggered by lack of disclosure to colleagues and/or clients. Moral distress, or knowing what to do in an ethical situation but not being allowed to do it, may also play a role.

Think about when a harmful mistake is acknowledged by the team but not shared with the client. How do those team members who are not in control of making that disclosure decision feel?

“I believe moral distress is one result of making a mistake or having an NM,” said Laurie Fonken, PhD, LPC, director of veterinary health and wellness programs at Colorado State University’s College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences (CVMBS). “For the veterinarian involved in these situations, there is a process of determining how to communicate about the situation and how to follow up. An observer of a mistake or NM may also experience moral distress, as they might not have control over how it is handled.”

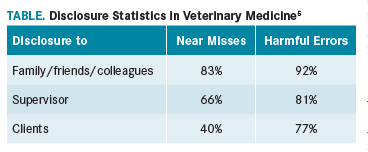

This year’s VIN survey study revealed that veterinarians disclose to their colleagues, family and friends 83 percent of NMs and 92 percent of medical errors that result in harm (Table). They report 66 percent of NMs and 81 percent of harmful medical errors to their supervisor, most commonly because it is ethically the right thing to do. Finally, veterinarians report 40 percent of NMs and 77 percent of harmful medical errors to clients. The survey’s respondents relayed that when they fail to report mistakes to their supervisors or clients, it’s usually because they fear confrontation, upsetting their supervisors and losing clients.5

Regina Schoenfeld-Tacher, PhD, one of the study’s authors,5 said, “Our research supported the hypothesis that NMs and harmful medical errors are not rare occurrences. They appear to result in both short- and long-term negative effects for a significant number of veterinarians. For many veterinarians, NMs and harmful medical errors lead to a diminished sense of job satisfaction and lower self-confidence. Clearly, this area warrants attention in the form of support systems and training to help veterinarians who have encountered these events.”

Knowing What to Do Next

Most veterinarians have had little training in what to do after making a mistake. But the good news is that training is available to help veterinary practitioners and students learn how best to disclose medical errors.

Linda Fineman, DVM, DACVIM (Oncology), director of veterinary talent and knowledge strategy at Ethos Veterinary Health, suggested that when veterinarians are communicating with clients about an NM or a harmful medical error, they use the TEAM model to structure their thinking. The approach is broken down into four pillars8:

- Truth: Tell the truth, explain the situation and then stop to ask how the client is feeling.

- Empathy: Use reflective listening to rebuild trust and restore the relationship.

- Apology: Saying you’re sorry is a vital part of making things right.

- Managing through to resolution: Describe changes being implemented to prevent the error from recurring and, if appropriate, offer compensation to the client and transfer of the pet to another facility.

According to Dr. Fineman, by recognizing the error and expressing empathy, “we’re showing clients that we hear, acknowledge and understand the issues they’re having. And that it’s OK for them to have emotions and negativity about the bad experience that they had.”9

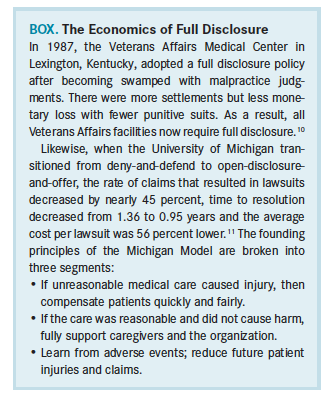

The American Veterinary Medical Association’s Professional Liability Insurance Trust (PLIT) encourages full disclosure, suggesting that if you’re concerned an error has been made or an upset client has threatened legal action, you should report the situation using the Notice of Potential or Actual Claim form. The insurance company will then contact you, and you can request to speak with a PLIT veterinarian for further guidance. This preference toward full disclosure has proved to be economically favorable in facilities outside veterinary medicine (Box).10-11

There are also opportunities for students to learn these valuable communication tools before they enter the profession. Since 2002, the Institute for Healthcare Communication’s Veterinary Communication Project has provided veterinary school faculty with training to address gaps in veterinarian-client communication training. To date, the project has produced 16 educational modules with tools and resources for improving communication skills on a variety of topics, including sharing bad news, managing team conflict and addressing ethical dilemmas.

At Colorado State University CVMBS, veterinary students receive 50 hours of communication training through the school’s Veterinary Communication for Professional Excellence curriculum.12 The program uses client simulations to teach critical communication skills, such as collecting a patient history, making a treatment plan, building trust and delivering bad news. The simulations are recorded and critiqued by peers, veterinarians and other professionals.

Lori Kogan, PhD, first author of the VIN survey study,5 said, “It is encouraging that some veterinary education programs are starting to implement courses describing cognitive errors and biases in the hopes of giving future veterinarians a language to talk about things when they go wrong, and help them think about strategies for reducing/preventing common errors.”

Owning Up Is a Valuable Tool

Admitting our errors is an important step in reclaiming personal power. Despite the difficulty in doing so, taking ownership of mistakes is essential because it allows us to assess our actions and take responsibility.

Admitting to and apologizing for mistakes are just the first steps. Veterinary professionals also need to amend their behaviors and work toward changing the system. Establishing system changes following a medical error is crucial to reducing the odds of recurrence. Such changes also foster a climate of openness that should make disclosure easier for the individual.

When faced with a medical error, many practitioners focus on the downside and become overwhelmed with fear. But Jane Shaw, DVM, PhD, an associate professor at Colorado State University CVMBS, reminds us that dealing with the aftermath of medical errors has great potential. “Disclosing medical errors effectively provides a path toward rebuilding trust and strengthening the relationship with your client,” she said. “Working through the conflicts that erupt within an organization after a medical error comes to light can strengthen relationships with colleagues and supervisors when a team comes together and faces such a challenge.”

Think of how much stronger your team could be after truthfully and successfully responding to a problem rather than sweeping it under the rug. I’ve found that being open to admitting mistakes starts with preparing the client at the outset of treatment for possible unexpected outcomes. Even if the prognosis is good, letting clients know there are risks with any treatment and providing at least a brief overview of what can go wrong will make it easier for them to accept unintended consequences.

Dr. Coles, a certified compassion fatigue professional (CCFP) and Missouri recovery support specialist-peer (MRSS-P), is a well-being advisor, medical writer and founder of Compassion Fatigue Coach. He is also the medical director at Two Dogs and a Cat Pet Club in Overland Park, Kansas.

References:

- Makary MA, Daniel M. Medical error—the third leading cause of death in the US. BMJ. 2016;353:i2139. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2139.

- James JT. A new, evidence-based estimate of patient harms associated with hospital care. J Patient Saf. 2013;9(3):122-128. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0b013e3182948a69.

- Harrison R, Lawton R, Stewart K. Doctors’ experiences of adverse events in secondary care: the professional and personal impact. Clin Med (Lond). 2014;14(6):585-590. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.14-6-585.

- Waterman AD, Garbutt J, Hazel E, et al. The emotional impact of medical errors on practicing physicians in the United States and Canada. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2007;33(8):467-476.

- Kogan LR, Rishniw M, Hellyer PW, Schoenfeld-Tacher RM. Veterinarians’ experiences with near misses and adverse events. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2018;252(5):586-595. doi: 10.2460/javma.252.5.586.

- Goldman B. Doctors make mistakes. Can we talk about that? TED website. ted.com/talks/brian_goldman_doctors_make_mistakes_can_we_talk_about_that. Published 2010. Accessed May 14, 2018.

- Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:397-422. doi: /10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397.

- Fineman L: To err is human. American Veterinarian®. 2018;3(1):32-33.

- Lengyel K. IVECCS 2017: Disclosing medical errors. Veterinarian's Money Digest website. https://www.vmdtoday.com/practice-management/iveccs-2017-disclosing-medical-errors. Published September 18, 2017. Accessed June 1, 2018.

- Cohen MR, American Pharmacists Association eds. Medication Errors. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Pharmacists Association; 2007.

- Helo S, Moulton CE. Complications: acknowledging, managing, and coping with human error. Transl Androl Urol. 2017;6(4):773-782. doi: 10.21037/tau.2017.06.28.

- Ryan S. Communication curriculum saves lives, builds relationships. Colorado State University College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences website. csu-cvmbs.colostate.edu/Pages/vcpe-curriculum-saves-lives.aspx. Published September 15, 2015. Accessed April 29, 2018.