Surgery STAT: Examining options to treat feline inflammatory polyps

Feline inflammatory polyps are benign growths originating from the middle ear of cats and can result in upper-airway obstruction, otitis externa and otitis media. The two most common methods of removal are by traction and ventral bulla osteotomy.

Feline inflammatory polyps (nasopharyngeal, middle ear, aural) are benign growths originating from the middle ear of cats and can result in upper-airway obstruction, otitis externa and otitis media.

Catriona MacPhail

Polyps are identified by otoscopic and/or nasopharyngeal examination. Diagnostic imaging (skull radiographs, CT) is indicated to document evidence of middle-ear disease. The origin and cause are unknown, but it is thought that polyps arise as a result of prolonged inflammation. It is unclear whether this inflammation initiates or potentiates the development and growth of inflammatory polyps.

Ongoing investigations into infectious-agent association with polyp development have yet to identify a definitive cause.

The two most common methods of polyp removal are by traction and ventral bulla osteotomy (VBO). Traction is effective; however, the owner must be made aware of the potential for recurrence.

Nasopharyngeal polyps are visualized by retraction of the soft palate using a spay hook or stay suture (Photo 1). Rarely does the soft palate need to be incised for polyp removal.

Photo 1: Intraoral photograph of a cat with a nasopharyngeal polyp with the soft palate retracted rostrally by a spay hook. (PHOTO: COURTESY OF DR. CATRIONA M. MACPHAIL)

Auricular polyps are visualized externally or by otoscopic examination. Regardless of location, the polyp is grasped with Allis tissue, alligator, or right-angled forceps and avulsed from its origin. Significant hemorrhage following traction removal is uncommon. A dental mirror or flexible endoscope helps visualize the nasopharynx following polyp removal to look for residual tissue.

Recurrence following removal by traction is reported to be approximately 40 percent; therefore conventional treatment advocates VBO to remove the epithelium of the tympanic bulla for definitive therapy.

However, one study describing prednisolone therapy following traction had a zero recurrence rate in eight cats vs. 64 percent recurrence in 14 cats receiving traction alone.

Response to prednisolone supports an etiology of chronic inflammation. Another study had recurrence in five of 14 (36 percent) cats treated with traction alone, but all of these cats had radiographic evidence of bulla disease. Results of these studies suggest that routine VBO for treatment of inflammatory polyps may not be necessary. Traction plus prednisolone may be a good option, particularly when no clinical signs or radiographic evidence of middle ear disease is present.

In cases of recurrence or chronic otitis media, exploration of the bulla from a ventral approach (VBO) is recommended. The cat is placed in dorsal recumbency with the head and neck extended over a sandbag or rolled towel. The bulla usually can be palpated through the skin. A small (3-4 cm) longitudinal incision is made over the bulla through skin and subcutaneous tissue. Blunt surgical dissection between the digastricus muscle laterally and the styloglossus and hyoglossus muscles medially, exposes the bulla, and residual tissue is removed from the ventral surface using periosteal elevators.

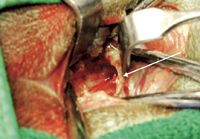

Photo 2: Intraoperative photograph of ventral bulla osteotomy. Soft tissues have been retracted using small Gelpi retractors. A hole has been made in the bulla using a large Steinmann pin. (PHOTO: COURTESY OF DR. CATRIONA M. MACPHAIL)

The hypoglossal nerve and lingual artery run medial to the hypoglossus muscle and should be protected.

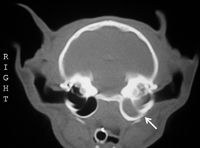

The bulla is entered using a Steinmann pin (Photo 2) or pneumatic drill. The osteotomy is enlarged using rongeurs. The feline bulla is unique in that it has two compartments divided by a bony septum (Photo 3). The larger ventromedial compartment is initially entered; the smaller dorsolateral compartment is opened by removing the septum (Photo 4).

Photo 3: A transverse CT image of the feline skull demonstrating a normal right tympanic bulla and an abnormal left tympanic bulla. The left bulla has thickened bone and is filled with a soft tissue density. The arrow is pointing to the bony septum separating the large ventromedial compartment from the smaller dorsolateral compartment. (PHOTO: COURTESY OF DR. CATRIONA M. MACPHAIL)

Fluid or exudate within the bulla should be collected and submitted for aerobic culture. Small curettes are used to remove the polyp (or polyp attachment) and epithelium of the bulla. Care should be taken when curetting the dorsomedial aspect of the bulla to avoid damaging the promontory over which the postganglionic sympathetic fibers run.

Photo 4: Intraoperative photograph of ventral bulla osteotomy. The opening in the bulla has been enlarged and both compartments have been exposed with the arrow pointing to the bony septum. (PHOTO: COURTESY OF DR. CATRIONA M. MACPHAIL)

Excised tissue is submitted for histopathology. The site is lavaged prior to closure. Drain placement is controversial and has been proven unnecessary in dogs following total ear-canal ablation and lateral bulla osteotomy.

Multiple complications can occur after VBO, including Horner's syndrome, vestibular disease, facial nerve paralysis, hemorrhage and recurrence.

Horner's syndrome also may occur after polyp removal by traction.

In either case, it is typically transient, lasting two to four weeks. In general, outcome following VBO is good to excellent.

Catriona MacPhail is an ACVS board-certified veterinary surgeon, currently on faculty at Colorado State University as a soft-tissue surgeon. Dr. MacPhail also completed her PhD in cardiovascular surgery in spring of 2007. Her primary clinical and research interests include upper and lower respiratory disease, wound management and reconstruction, gastrointestinal surgery and minimally invasive surgery.