Achieving their dream

The owners of Causeway Animal Hospital in Metairie, La., asked architects Michael K. Crosby and Sal Longo Jr. to draw elevations for a new facility. But the architects yearned to design the entire building, so they produced extensive computer renderings and predicted they'd build Veterinary Economics' Hospital of the Year.

By Carolyn Chapman, special assignments editor

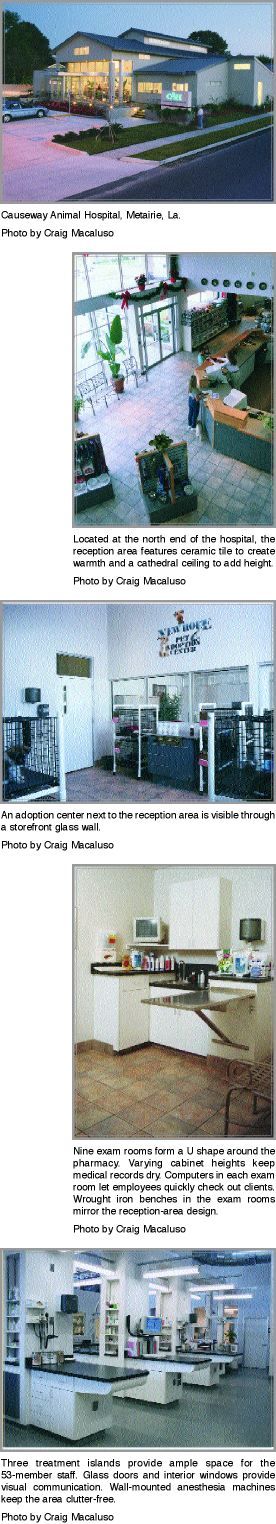

The owners of Causeway Animal Hospital in Metairie, La., asked architects Michael K. Crosby and Sal Longo Jr. to draw elevations for a new facility. But the architects yearned to design the entire building, so they produced extensive computer renderings and predicted they'd build Veterinary Economics' Hospital of the Year.

Chuckling, the doctors asked them to simply design a facility that offered more space and nicer materials than their cramped, aging hospital. Undaunted, the architects fulfilled their promise, creating a 12,520-square-foot facility that won Veterinary Economics' 2000 Hospital of the Year Award.

Judges lauded the facility's traffic flow, observation deck, and exam-room arrangement. "This plan is well-executed, especially for such a large hospital," one judge said. "The traffic flow and segregation of spaces is excellent," another remarked.

The client who could

Dr. Martin St. Germain opened Causeway Animal Hospital just two years after graduating from Texas A&M University in 1970. He converted a 30-year-old, 3,000-square-foot house along a major route. Soon, friends Drs. Thomas A. Pelle and Leslie B. Fleming merged their practices with Causeway Animal Hospital. In 1977, the partners renovated and added 1,500 square feet. When Dr. Fleming retired in 1982, Dr. Marlon J. Rovira became a partner. A fourth partner, Dr. Marcelo D. Gentinetta, joined the practice in 1990.

A prime site just three blocks from their old hospital drew the partners' interest. As a child, Dr. Rovira lived in a house on the property. "After a hurricane flooded the land in 1947, the owner offered to sell it to my dad for $1,500," recalls Dr. Rovira. "When I told Dad we paid $531,000 for that site, he thought I'd lost my mind."

Just before they closed the land deal, the partners learned zoning restrictions prohibited a kennel within 100 feet of a residential area. "Our hearts sank," Dr. St. Germain says. They'd essentially given up on building their dream hospital when a client who lived behind the site said, "I heard we were almost neighbors." Armed with hospital literature and floor plans, Flossie Laborde and an army of neighbors persuaded the zoning board to approve construction of the veterinary hospital.

A few roadblocks delayed construction. The doctors had to wait a week while the city found a qualified person to remove a water meter. Then they paid $25,000 to demolish the Italian restaurant on the site. But once the building was removed, zoning reverted back to residential, forcing them to request rezoning.

Designed in four zones

To overcome zoning restrictions, the architects placed kennels along the west wall--100 feet from houses to the east. This forced the architects to design Causeway Animal Hospital in four parallel zones. Zone 1 contains animal housing; zone 2 features grooming, radiology, a staff lounge, and the special procedures room; zone 3 houses the working areas; and zone 4 includes the conference room and doctors' office.

All four partners helped plan the facility. They met weekly with the architects to review drawings and models. Three-dimensional models and computer renderings gave the doctors a true sense of traffic flow and space.

The original design included a unique curved roofline, but Dr. Pelle thought a classic pitched roof would make a bolder statement and last longer. The architects presented models of both concepts, and all agreed on the pitched roof. "To soften the building front, we added a pillar, a curved wall with glass-block accents, a fountain, and extensive landscaping," Dr. Pelle says.

Inside, earth tones and an etched-glass window above the reception desk provide inviting touches. Retail displays mounted on wheels break up the reception area. An adoption center occupies the west side, and the cat waiting area is on the east side.

Behind the reception desk, nine exam rooms line the central pharmacy, letting doctors circulate between rooms with fewer interruptions. "In the old facility clients could see us from the front desk and wanted to chat," says Dr. Pelle. "That fostered good client relations, but it often put us behind schedule. With the new design, we're more efficient." Computers in exam rooms permit quick client checkout and eliminate congestion at the reception desk. A bonus: Staff members don't discuss fees or payment in public areas.

Three work islands in the treatment area accommodate the 53-member team. To better monitor recovery, technicians place animals on pads in lighted cubicles divided by glass blocks. "Animals are visible but out of the way," Dr. Pelle explains. The surgery room is divided into one dual and one single suite, with the single suite reserved for orthopedic and neurologic surgeries.

Although they hesitated to add the second-floor observation deck, doctors definitely enjoy it. The deck gives visitors a birds-eye view of the treatment area, and a glass roof over the dual surgery suite permits viewing as well. Children on field trips, scout troops, and nursing students regularly use the deck to watch veterinary medicine in action. "I didn't think we needed the observation deck, but we all love it," Dr. St. Germain says.

To make the kennel more comfortable and attractive, Dr. Pelle designed an interior walking area with tropical plants and washable coconut mats. Sloped ceilings and insulated concrete block walls help muffle sounds. With just a flip of a lever, staff members can fill water bowls in all 37 runs simultaneously. And above every third run, doctors mounted a small hose with a nozzle so staff members can clean without dragging around a long, heavy hose.

Going first class

Because the partners made major design decisions during construction, the project exceeded budget by $350,000. They chose materials and features whose future benefits outweighed current costs. "Everything costs more when you go first class," Dr. Pelle says. Bank officials fell in love with the project, so their loan officer extended credit when needed.

Dr. St. Germain wanted to control costs, but he says they refused to sacrifice quality to save money. For example, the contractor chose to paint a concrete block wall between the kennel and the main client hallway to cut costs. But the partners didn't like the look and paid to refinish it.

The builder also tried to eliminate the curved exterior wall because subcontractors complained it was hard to construct. And the doctors held their ground when the builder pushed for steel door frames and painted doors instead of aluminum frames and plastic-laminate doors. "We knew which materials would last 20 years in a veterinary hospital," Dr. St. Germain emphasizes. The transoms over the exam-room doors proved another point of contention. The builder claimed they cost too much, but the architects knew the exam rooms needed natural light from the pharmacy clerestory windows.

For a building project to succeed, the entire team must stay committed, Dr. St. Germain says. Hiring dedicated architects who are open to suggestions helped the project proceed smoothly. And before construction began, the partners and architects visited several award-winning hospitals, including Veterinary Economics' 1994 Hospital of the Year, Animal Medical Hospital in Charlotte, N.C., owned by Drs. Richard and Susan Coe. "The Coes gave us courage," says Dr. St. Germain. "We tried to learn as much from what they did wrong as what they did right."

High-fives filled the practice when team members learned Causeway Animal Hospital had won the award. A project that began with the architects' promise three years ago had come true. As soon as Dr. St. Germain received the news, he called the architects and said, "Congratulations! You built the Veterinary Economics' 2000 Hospital of the Year!"

Carolyn Chapman, a former Veterinary Economics associate editor, is a freelance writer in Liberty, Mo.

March 2000 Veterinary Economics