Ameliorating our incompetence with urinary incontinence: Artificial urethral sphincters

Amidst the many treatment options for incontinence related to urethral sphincter mechanism incompetence, this surgical technique may offer an alternative for those patients refractory to traditional therapies.

Urinary incontinence is generally defined as the inability to voluntarily control urination. Instead of appropriate storage of urine in the bladder until intentional voiding occurs, urine escapes prematurely. Clinically, this results in intermittent or continuous dribbling of urine. It is important to note, however, that normal urination behaviors may also be observed in some incontinent patients. Most often, incontinence is due to failure of the storage phase of micturition (meaning that the urethral closure mechanism is defective), restricted filling of the bladder, anatomic defects (e.g. ectopic ureters) or neurogenic abnormalities.

Multiple factors contribute to overall urethral resistance and continence. These include urethral muscle tone, urethral elasticity, urethral physical properties such as length and diameter, and intra-abdominal pressure acting on the outer surface of the urethra. These combined factors comprise the urethral sphincter mechanism. Therefore, urinary incontinence, as a result of abnormal function of the urethral sphincter mechanism, is called urethral sphincter mechanism incompetence (USMI).

USMI can lead to urinary incontinence in dogs and cats of both sexes and may be congenital or acquired. However, USMI is largely an acquired condition of adult, female, spayed, large-breed dogs and reportedly affects 5.1% to 20.1% of this population. The onset of incontinence typically occurs three to five years after an uneventful ovariohysterectomy, making many dogs middle-aged at the time of diagnosis. Although urine leakage during recumbency is the most common historical finding in dogs with uncomplicated USMI, urinary tract infections may develop because of the wicking effect of a urine-soaked perineum and bacterial ascent associated with decreased urethral pressure.

Diagnosis

Previous research has suggested that USMI is the primary cause of urinary incontinence observed in veterinary practice. The diagnosis is largely based on patient signalment, history and physical examination findings. Although a minimum database, including a urinalysis with culture and sensitivity, should be performed in all patients, additional diagnostics, such as ultrasound, contrast radiography, computed tomography and cystoscopy may be necessary to exclude other causes of incontinence.

Because of the prevalence of USMI in middle-aged spayed female dogs, the typical clinical presentation, and the relative safety of the drugs used to treat the condition, some clinicians advocate diagnosing the condition by empirically treating suspected cases. A definitive diagnosis of USMI, however, can only be obtained by documenting decreased urethral closure pressure by urethral profilometry, which requires specialized urodynamic equipment.

Medical management

Numerous options exist to treat USMI, though none have achieved uniform success. Urethral sphincter mechanism incompetence may be fully, partially, or transiently responsive to pharmacologic management. The mainstays of medical management include:

• Alpha-adrenergic agonists-such as phenylpropanolamine at 1 to 1.5 mg/kg orally every eight to 12 hours

• Estrogens-such as diethylstilbestrol at 0.1 to 1 mg/dog (0.02 mg/kg, maximum dose of 1 mg) orally once daily for three to five days followed by a maintenance dose of 1 mg/week or a maximum of 0.1 mg/kg/week, with the lowest effective dose given

Phenylpropanolamine increases urethral tone by stimulating alpha-adrenergic receptors in the urethra and diethylstilbestrol increases smooth muscle contractility and the number or sensitivity of alpha-adrenergic receptors in the urethra. About 60 to 90 percent of female patients will respond well to one or a combination of these therapies, whereas males are less likely to respond, with less than 50 percent showing improvement. These therapies are associated with a number of potential side effects, require intermittent monitoring, and must be administered for the remainder of the animal's life.

Traditional surgical interventions

Nonmedical treatment of USMI is typically reserved for patients that have failed pharmacologic intervention, that have adverse reactions to the recommended medications, or that have concurrent conditions that preclude the use of medical therapies. The goal of alternative therapies is to increase urethral resistance to the outflow of urine. To accomplish this, procedures focus on reducing the diameter of the urethral lumen, correcting caudal displacement of the bladder neck to increase intra-abdominal forces acting on the urethra, and improving the functional length of the urethra.

Urethral bulking agents can be administered via cystoscopy. The procedure involves the placement of small blebs of collagen, polytetrafluoroethylene (e.g. Teflon) or other material into the urethral submucosa to effectively narrow the urethral diameter. This procedure has been shown to achieve urinary continence in 68 percent of treated patients for durations of one to 64 months (mean 17 months). It has also been used with success in male dogs and in patients that remain incontinent after ectopic ureter correction. The primary limitation of this procedure appears to be its temporary nature. Unfortunately, the high cost and limited availability of bovine collagen products have significantly reduced the use of this technique in veterinary medicine.

Colposuspension has historically been the surgery most commonly used to treat urethral sphincter mechanism incompetence in female dogs. During this procedure, sutures are placed from the cranial vagina (on either side of the urethra) to the prepubic tendon. This draws the bladder neck and proximal urethra cranially, reduces the urethral diameter due to positioning over the pelvic brim and compression with the vagina, and increases functional urethral length. Reported long-term continence rates for this surgery range from 13% to 53%.

Additional surgical techniques described for dogs with refractory USMI include urethropexy, urethral lengthening, periurethral slings and others. Overall, surgical treatment options appear to have good short-term efficacy but poor long-term results with restoration of continence in only 14 to 56 percent of patients. The current lack of effective surgical intervention in those patients refractory to medical treatment is important, as persistent incontinence may ultimately lead to euthanasia.

Regardless of treatment, most affected pets become progressively worse with time. This phenomenon has led to the search for effective alternative therapies for patients with urinary incontinence that are refractory to traditional treatments.

Artificial urethral sphincters

Recently, another treatment for urinary incontinence has gained in popularity and availability. The formation of a custom-designed, percutaneously controlled static hydraulic urethral sphincter was first described in 2004 in a study that evaluated the urodynamic effects of the sphincter in six cadavers.1 A silicone cuff was placed around the proximal urethra, secured and connected to a subcutaneous infusion port via actuator tubing. The device was inflated or deflated by percutaneous injection or aspiration of fluid. It was observed to induce compression of the urethra and lead to improvements in urodynamic parameters including maximal urethral closure pressure and cystourethral leak point pressure. These results indicated that the implant could be used in a static mode in live dogs to increase urethral resistance by adjusting the sphincter to prevent urine leakage, while still allowing voluntary voiding.

The efficacy of an artificial urethral sphincter (AUS) for the treatment of acquired, refractory USMI in four female spayed dogs was studied in 2009.2 In the study, continence scores improved from a median preoperative score of 3/10 to 10/10 postoperatively. All four dogs were continent, without medical management, for 26 to 30 months after AUS placement.

Figure 1. A urethral cuff, or occluder. (All photos courtesy of Dr. Heather Hadley)Since then, several other authors have reported the use of an AUS device as an effective long-term treatment for refractory urinary incontinence, when traditional options failed. Thus far, 70 to 80 percent of dogs have become continent without cuff inflation, and inflation of the cuff has primarily been used to improve continence in dogs that have regressed after one or more years of follow up.

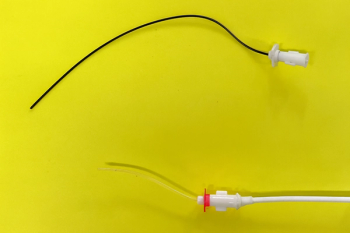

Surgical procedure. Supplies needed to place an AUS include a medical grade silicone urethral cuff (Figure 1), a vascular access port (Figure 2), a Huber needle (special noncoring needle) (Figure 3), an over-the-needle catheter and nonabsorbable suture.

Figure 2. A vascular access port.

Figure 3. A Huber needle.After general anesthesia has been induced, the patient is clipped, prepped and draped routinely for abdominal surgery. A caudal midline approach to the urinary bladder is performed. The bladder is retracted cranially, and a small section of the pelvic urethra (site of proposed urethral cuff) is isolated from the periurethral adipose tissue via blunt dissection. The circumference of the urethra is measured with a Penrose drain or strand of suture. A urethral cuff is selected based on this measurement, erring on the larger side to avoid excessive urethral compression.

Before placement, the AUS unit is tested and primed with sterile saline solution to flush air from the cuff, tubing, and port and to test for leakage. The cuff is secured around the urethra (approximately 2 to 3 cm caudal to the trigone of the bladder in female dogs and 2 cm caudal to the prostate in male dogs) by placing 2-0 to 0 polypropylene sutures through the islets and tying a secure knot (Figure 4).

Figure 4. The AUS occluder secured around the urethra.The infusion line is passed through a stab incision in the abdominal wall and is tunneled subcutaneously to the desired location of the port (lateral to the rectus abdominis muscle and cranial to the flank fold) (Figure 5).

Figure 5. A properly positioned AUS and infusion port.

The AUS tubing is then cut to an appropriate length, avoiding the formation of kinks. The tubing is secured to the infusion port and reinforced with a suture or plastic boot.

The full system is checked one additional time to ensure proper function. The total infusion volume to achieve closure of the urethral cuff is measured and recorded. The fluid is withdrawn. The infusion port is then anchored to the superficial fascia of the abdominal wall with nonabsorbable suture (Figure 6). The abdomen and incision for port placement are closed routinely.

Figure 6. The infusion port secured to the fascia.Intravenous fluid therapy, analgesics and antibiotic therapy (if warranted) are administered postoperatively. Patients are monitored in the hospital for 24 hours after surgery to monitor for signs of urethral obstruction (e.g. failure or inability to urinate, pollakiuria, stranguria, weak or interrupted urine stream, abdominal distention or pain). After normal urination is observed, the patient is discharged.

Follow-up. Dogs are allowed to recover for four to six weeks before the urethral sphincter is inflated. A delay in inflation is recommended to allow revascularization of the dissected portion of urethra and to decrease the incidence of urethral atrophy. In dogs with persistent incontinence after the recovery period, the skin above the port is clipped and aseptically prepared. A small volume (based on the previously measured filling volume) of 0.9% sodium chloride is injected into the subcutaneous infusion port using a 22-ga, noncoring needle (Huber needle). Sphincter occlusion should be very gradual and may require several adjustments. After each injection, the patient should again be monitored in hospital until normal urination has occurred.

Overall, the results reported in the literature are very encouraging and indicate that the AUS is an alternative treatment option for dogs with USMI. However, additional cases are needed to fully evaluate the short- and long-term efficacy of the AUS, the reliability of the implants, and associated complication rates. This technique has been associated with the major complication of urethral obstruction, which has required implant removal. Because of potential complications and the invasive nature of any surgical technique, this procedure is only recommended in dogs that are refractory to medical therapy, that do not tolerate prescribed medications, or that have failed other interventions.

Unfortunately, it appears unrealistic to expect to achieve complete continence in all patients, especially in those with concurrent anatomic abnormalities or urinary dysfunction. Therefore, appropriate case selection, owner counseling and surgeon experience (with the equipment, procedure, and postoperative monitoring) are important for success.

Dr. Heather Hadley is an ACVS board-certified veterinary surgeon with BluePearl Veterinary Partners in Eden

Prairie, Minnesota. She is passionate about all facets of soft tissue and emergency surgery. While off duty, Dr. Hadley enjoys spending time with her husband, their daughter and three furry children adopted from around the country (a miniature dachshund from Minnesota, a tabby cat from Colorado, and a coonhound from Michigan).

Surgery STAT is a collaborative column between the American College of Veterinary Surgeons (ACVS) and dvm360 magazine. To locate a diplomate, visit ACVS's online directory, which includes practice setting, species emphasis and research interests, at

References

1. Adin CA, Farese JP, Cross AR, et al. Urodynamic effects of a percutaneously controlled static hydraulic urethral sphincter in canine cadavers. Am J Vet Res 2004;65:283-288.

2. Rose SA, Adin CA, Ellison GW, et al. Long-term efficacy of a percutaneously adjustable hydraulic urethral sphincter for treatment of urinary incontinence in four dogs. Vet Surg 2009;38:747-753.

Suggested reading

1. Acierno MJ, Labato MA. Canine incontinence. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet 2006;28(8):591-600.

2. Angioletti A, De Francesco I, Vergottini M, et al. Urinary incontinence after spaying in the bitch: incidence and oestrogen-therapy. Vet Res Commun 2004;28 (suppl 1):153-155.

3. Barth A, Reichler IM, Hubler M, et al. Evaluation of long-term effects of endoscopic injection of collagen into the urethral submucosa for treatment of urethral sphincter incompetence in female dogs: 40 cases (1993-2000). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2005;226:73-76.

4. Berent AC, Weisse CW, Adin C, et al. The use of a percutaneously controlled hydraulic occluder for the treatment of urethral sphincter mechanism incompetence in 11 dogs and 1 cat, in Proceedings. American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine, Montreal, 2009.

5. Currao RL, Berent AC, Weisse C, et al. Use of a percutaneously controlled urethral hydraulic occlude for treatment of refractory urinary incontinence in 18 female dogs. Vet Surg 2013;42:440-447.

6. Dean PW, Novotny MJ, O'Brien DP: Prosthetic sphincter for urinary incontinence: results in three cases. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 1989;25:447-454.

7. Forrester SD. Urinary incontinence. In: Ettinger SJ, Feldman EC, eds. Textbook of veterinary internal medicine. St. Louis: Saunders, 2005;109-114.

8. Holt PE. Canine urethral sphincter mechanism incompetence. In: Bojrab MJ, Monnet E, eds. Disease mechanisms in small animal surgery. 3rd ed. Jackson: Teton New Media, 2010; 409-413.

9. Holt PE. Urinary incontinence. In: Urological disorders of the dog and cat: investigation, diagnosis, and treatment. 1st ed. London: Manson Publishing, 2008;134-159.

10. Hussain M, Greenwell TJ, Venn SN, et al. The current role of the artificial urethral sphincter for the treatment of urinary incontinence. J Urol 2005;174:418-424.

11. Massat BJ, Gregory CR, Ling GV, et al. Cystourethropexy to correct refractory urinary incontinence due to urethral sphincter mechanism incompetence. Preliminary results in ten bitches. Vet Surg 1993;22:260-268.

12. McLoughlin MA, Chew DJ. Surgical treatment of urethral sphincter mechanism incompetence in female dogs. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet 2009;31:360-373.

13. Reeves L, Adin C, McLoughlin M, et al. Outcome after placement of an artificial urethral sphincter in 27 dogs. Vet Surg 2013;42:12-18.

14. Sajadi KP, Terris MK. Artificial urethral sphincter, in E Medicine (www.emedicine.medscape.com), 2008.

15. Stocklin-Gautschi NM, Hassig M, Reichler IM, et al. The relationship of urinary incontinence to early spaying in bitches. J Reprod Fertil 2001;57 (suppl):233-236.

Newsletter

From exam room tips to practice management insights, get trusted veterinary news delivered straight to your inbox—subscribe to dvm360.