Asymptomatic Bacteremic Cats Constitute Major Parasitic Reservoir

Feline, Manx, 1 year old, male castrated, 7.8 lbs.

Signalment

Feline, Manx, 1 year old, male castrated, 7.8 lbs.

Clinical history

The young cat had originally been purchased from a highly populated cattery and has been seen since it was a kitten for his routine vaccinations and neutering/declawing procedures.

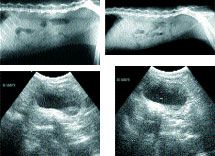

(Top left) Photo 1, (Top right) Photo 2, (Bottom left) Photo 3, (Bottom right) Photo 4

There have been no significant problems noted until the owner presented the 11-month-old cat on May 21 because he was not eating and possibly losing weight. The results from the CBC and serum chemistry profile were within normal limits.

The cat tested negative for FeLV and FIV, and tested serologically positive at 1:40 for FIP. No fecal sample was available for parasite examination. The cat then re-presents on June 6 for thoracic and abdominal radiography. The owner has tried different diets at home, and the cat continues to pick at its food. Fecal examination was positive for roundworm eggs and bacteriuria was noted in urinalysis. The returned urine culture results were negative for bacterial growth. The cat was dewormed and sent home again on antibiotics.

Physical examination

The findings on June 13 show rectal temperature of 100.8��F, heart rate of 200 beats/min, pink mucous membranes, normal breathing pattern, CRT <2.0 sec and thin body condition. Normal thoracic auscultation is noted. The cat shows consistent vocal sounds and grumpy when abdomen is palpated as if he is uncomfortable. Flea dirt is noted.

Laboratory results

A complete blood count, serum chemistry profile and urinalysis were repeated on June 13 and are outlined in Table 1.

Radiographic review

Survey thoracic and abdominal radiographs are done. The thoracic radiographic views are unremarkable. The lateral abdominal radiographs were taken on June 6 and 13 (Photos 1-2).

My comments

The abdominal radiographs on June 6 show the greatly enlarged sublumbar lymph nodes. On June 13, the sublumbar lymph nodes are not as enlarged.

Table 1

Ultrasound examination

Thorough abdominal ultrasound is performed with the cat positioned in dorsal recumbency. The ultrasound images provided are of the urinary bladder and sublumbar region. Note the enlarged sublumbar lymph nodes (Photos 3-4).

My comments

The liver parenchyma shows uniform echogenicity. No obvious masses noted in the liver parenchyma. The gallbladder is mildly distended, and its walls are not thickened or hyperechoic. The spleen has normal uniform echogenicity - no masses noted. The left and right kidneys are similar in size, shape and echotexture. No masses or calculi were noted in either kidney. The urinary bladder is distended with urine and contains some urine sediment material - no masses or calculi noted. There appears to be enlarged, uniform echogenic sublumbar lymph nodes adjacent to the urinary bladder.

Case management

The tentative diagnosis is enlarged sublumbar lymph nodes of unknown origin �� most likely inflammatory lymph node enlargement or lymphoma. Such lymphadenopathy in young cats may be from bite wounds around the tail region that extended to the local lymph node or from the lymphadenopathy of feline bartonellosis. Fleas in cats transmit Bartonella organisms.

In this cat, I would suspect feline bartonellosis and not lymphoma. To differentiate between inflammatory lymph nodes versus lymphoma, an ultrasound-guided lymph node biopsy for histopathology would be recommended. Otherwise, the cat should be tested for feline bartonellosis. I would also consider rechecking by way of abdominal radiography the sublumbar lymph node region in one to two weeks. I suspect these lymph nodes will continue to decrease in size during this time period.

Let's review feline lymphadenopathy and feline bartonellosis.

Feline lymphadenopathy

Lymph nodes are expected to respond to various local and systemic inflammatory, infectious and neoplastic stimuli. Lymphadenopathy may be characterized by enlargement of lymph nodes that are normally palpable, the presence of lymph nodes that are not usually apparent on examination or lymph nodes that are simply altered in texture on palpation. Sublumbar and mesenteric lymph nodes must be enlarged to be detected on rectal or abdominal palpation or survey radiography. Two basic mechanisms result in lymphadenopathy.

First, and most commonly, there can be increased number and size of lymphatic follicles with proliferation of lymphocytes and reticuloendothelial elements (immune stimulation). Second, infiltration of cells that are not normally found in the lymph node (neoplasia) could produce lymphadenopathy.

Evaluation of lymphadenopathy should include a detailed case history and physical examination. Distribution of the lymphadenopathy is important in determining the type of underlying disease process. If one lymph node or regional group of lymph nodes is involved, the sites drained by these lymph nodes should be carefully examined for evidence of inflammation, infection or neoplasia. If lymph node involvement is more widespread, primary lymphoid neoplasia or diseases causing systemic antigenic stimulation should be considered. Useful diagnostic tests include aspiration cytology, biopsy for histopathologic evaluation, bacterial culture, laboratory testing including serology and PCR testing, survey radiography and ultrasonography.

Aspiration cytology can be particularly useful and cost-effective screening test when evaluating animals with lymphadenopathy. The largest lymph node is usually not ideal for the aspiration procedure because it may have a necrotic center and areas of hemorrhage.

Mandibular lymph nodes are also not ideal since they typically have reactive changes associated with regional drainage from the oral cavity. Cytology may provide a definitive diagnosis when bacteria or fungi are identified and/or in the rare circumstance of large cell lymphoma.

Cytology can also provide a supportive picture of reactive changes that can occur secondary to local or systemic antigenic stimulation with increased numbers of inflammatory cells including plasma cells, neutrophils, eosinophils and macrophages.

Several specific disorders affecting lymph nodes in young cats deserve particular attention. Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia can present as a transient generalized lymphadenopathy, which may develop in the initial viremic stage of many viral infections, including FeLV and FIV.

These cats are typically young (5 to 24 months old) and lymph nodes are judged to be two to three times the normal size. Infections in young cats with one of the Bartonella species will also contribute to a lymphadenopathy and most likely be reported by the veterinary pathologist as reactive lymphoid hyperplasia. Lymphoma is rare in cats younger than 12 months. When neoplasia is diagnosed in young cats, hematopoietic neoplasms and lymphoma predominate. Cats with lymphoma should be tested for FeLV and FIV, as both viruses may be associated with an increased incidence of lymphoproliferative disease.

In young cats, anterior mediastinal is the most frequent form of lymphoma and is often associated with positive retrovirus infection.

Feline Bartonellosis

Bartonella bacteremia is common in domestic cats in the United States. Nationwide, 28 percent of apparently healthy cats are seropositive to the organism and bacteremia has been documented in 25-41 percent of healthy cats. Most domestic cats that have Bartonella bacteremia are not ill. Bartonella species have been cultured from fleas obtaining blood meals from naturally infected cats. Kittens younger than 1 year of age, kittens or older cats infested with fleas, and feral cats or former strays are most likely to have Bartonella bacteremia. Asymptomatic bacteremic cats constitute a major reservoir of Bartonella species. Bartonella species are classified as being type one - isolated from infected humans, or type two - isolated from infected animals like the domestic cat. Isolates of type one when inoculated into domestic cats do not cause any clinical signs or obvious diseases. Isolates of type two when inoculated into domestic cats will cause clinical signs and make the infected cat clinically sick for a few weeks. When a susceptible cat is infected with a type two Bartonella isolate, clinical signs should be expected.

Clinical signs associated with Bartonella infection are anorexia, fever, hypersensitivity to noise and/or light, vestibular signs and/or lymphadenopathy. The whole course of possible clinical signs will generally last for about 14 to 21 days. The fever (104 degrees-106 degrees F) will usually only be present for about four days. The lymphadenopathy being the most obvious clinical sign may persist for an extended period of time. The brain and bone marrow are likely sites for latency of Bartonella organisms in an infected cat. When stressors are applied to the latently infected cat, Bartonella organisms will come out of latency and then infect feeding fleas.

Furthermore, serum antibody positive cats when inoculated with flea feces will develop a short-term bacteremia but show no clinical signs. Serum antibody negative cats when inoculated with flea feces will develop short-term bacteremia and show clinical signs of Bartonella infection.

Diagnosis of feline bartonellosis generally requires culturing the organism from whole blood or other infected tissues. It normally will take at least four weeks to successfully grow the organism in the diagnostic laboratory. The Western immunoblot can be used effectively to identify seropositive cats. My preferred diagnostic test for diagnosing feline bartonellosis is PCR.

Antimicrobial therapy doesn't necessarily shorten the duration of illness. Doxycycline, erythromycin and rifampin are recommended, but clinical improvement has been reported following the use of penicillin, gentamicin, ceftriaxone, ciprofloxacin and azithromycin. Treatment for two weeks in immunocompetent individuals and six weeks in immunocompromised individuals is generally recommended.

Relapses, associated with bacteremia, do occur in immunocompromised animals despite appropriate antimicrobial therapy. Antimicrobial therapy has not been well established for eliminating Bartonella bacteremia in domestic cats.

Dr. Hoskins is owner of DocuTech Services in Baton Rouge, La. He is a diplomate of the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine with specialties in small animal pediatrics. Formerly a professor in the School of Veterinary Medicine at Louisiana State University, Hoskins is also the author of clinical textbooks on pediatrics and geriatrics. He founded an Internet service called "Vet-Web.com", where pet owners can e-mail animal health-related questions and he responds via e-mail. He can be reached at (225) 751-9272.