Bionic Burton: 10 titanium plates used to heal Labrador's shattered face

Veterinary orthopedist Randy Boudrieau takes a page from human medicine using titanium plates narrower than a pencil to repair fractured facial bones.

Burton, a chocolate labrador retriever, successfully recovered from intricate reconstructive facial surgery performed by Randy Boudrieau, DVM, DACVS, professor of Clinical Sciences at the Foster Hospital for Small Animals. Photo by Alonso Nichols, courtesy of Tufts UniversityWhen owner Janine Stuczko first saw her 4-year-old Labrador retriever, Burton, after a car hit him, she opened his bloodied mouth because she thought he had eaten glass. “I heard all the bones in his muzzle grinding, like fingernails on a chalkboard,” she says. “It was awful. His muzzle was squished down to his eye socket.”

Facial fractures are common in people who fly through a windshield in a car accident, says Randy Boudrieau, DVM, DACVS, a professor at Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine at Tufts University. But these injuries are pretty rare in dogs, he says, so most veterinarians have limited experience treating them. Canine facial fractures may be left to heal on their own if they are relatively stable, or they may be wired together if the bone fragments are large enough. However, these techniques often aren't effective with bones that break into many small pieces.

Image courtesy of Tufts University

Click here to flip through Burton's story as an interactive feature.

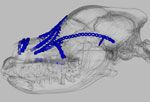

In human and animal orthopedics, the prevailing theory is that “the best way to manage the pain from broken bones is to stabilize them so they're not moving anymore,” Boudrieau says. Craniofacial surgeons stabilize facial fractures in people by attaching metal plates to the “buttresses,” or thicker portions of the facial skeleton. In 1980, anatomist and physical anthropologist E. Lloyd Du Brul first described these buttresses by putting a light inside a human skull to determine the location of the thick and thin areas. The light, Boudrieau says, “would shine through the thinner parts, identifying the thicker areas, which were termed the pillars or buttresses.”

Using a similar technique, Boudrieau mapped the location of canine buttresses by installing a Christmas tree light inside a dog skull and taking photographs. (He was caught red-handed by his wife on Christmas day.) His findings have been published in several veterinary textbooks and journals.

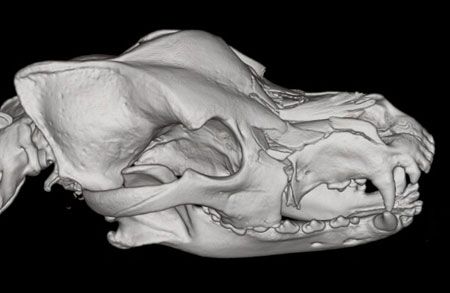

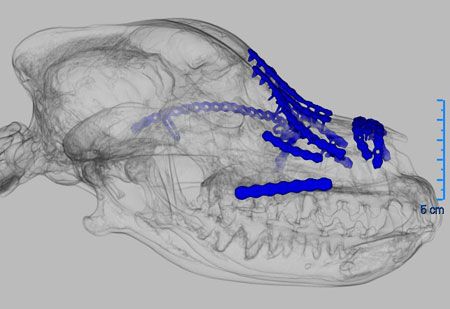

A left oblique 3D reconstruction of a CT scan of Burton preop. Photo courtesy Tufts UniversityHe then evaluated the effectiveness of different titanium plates used in human and veterinary medicine to repair facial fractures that involved many small pieces. Boudrieau found that similar to human medicine, plates that can be bent three-dimensionally work best. Stuczko's dog, Burton, was his most recent case, published in Veterinary and Comparative Orthopaedics and Traumatology in August 2014. Brought to Foster Hospital for Small Animals after the accident, Burton had multiple fractures of his face, including the nose, cheek and eye socket. His maxilla (essentially the snout) had separated from the base of his skull.

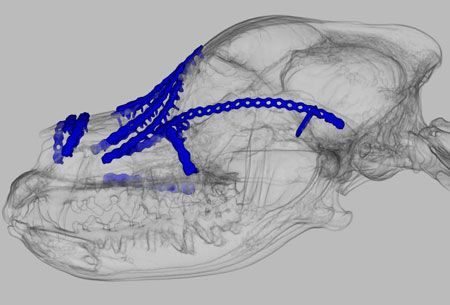

A right oblique 3D reconstruction of a CT scan of Burton preop. Photo courtesy of Tufts University

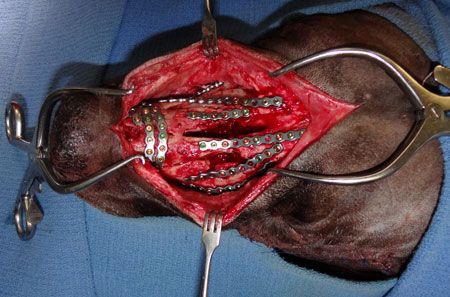

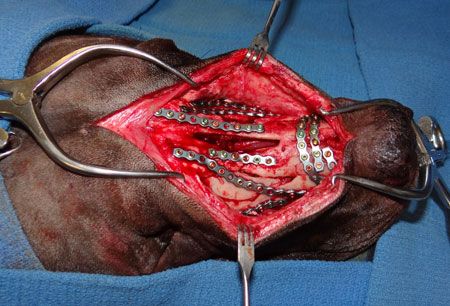

An image of Burton's intraop left oblique shows the use of titanium plates that can bend three dimensionally. Photo courtesy of Tufts UniversityOnce in surgery, Boudrieau lined up Burton's facial bones with the jaw by using the places where the upper and lower teeth would normally come into contact as anatomic landmarks. “The whole idea is that you work on the simplest fracture first and gradually proceed sequentially through the more difficult areas,” he says, while “trying to stay in the areas of the thicker bone-a.k.a. the buttresses.” During the five-hour operation, Boudrieau implanted 10 titanium plates.

An image of Burton's intraop right oblique shows the titanium plates, 10 in all, used to repair his shattered facial bones. Photo courtesy of Tufts University

A 3D reconstruction of a low opacity CT scan showing the left lateral view. Courtesy of Tufts University

A 3D reconstruction of a low opacity CT scan showing the right lateral view. Courtesy of Tufts University

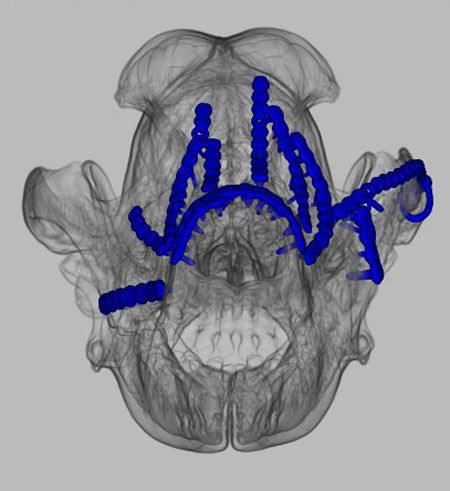

A 3D reconstruction of a low opacity CT scan showing the AP view. Courtesy of Tufts University

Burton was in surgery for five hours. Courtesy of Tufts UniversityThe morning after his surgery, Burton was comfortably eating soft foods. Stuczko says her pet has “healed up perfectly.” Some 21 months after his accident, “he's very playful,” she reports, although he won't be “going through any metal detectors any time soon.”

The morning after surgery, Burton was eating soft food. Courtesy of Tufts University

Burton two weeks post op. Courtesy of Tufts University

Burton, 13 months after surgery. Courtesy of Tufts University“Burton is a good example of a bad case,” says Boudrieau, “and these cases are very rewarding.”

He advocates more aggressive treatment of craniofacial fractures. “What I basically propose is to stop treating these cases conservatively,” he says. “We have the equipment to fix them. You can go from a dog that looks and feels like hell to one that's comfortable and eating by the next day.”

Reprinted with permission, Cummings Veterinary Medicine magazine, © 2015 Tufts University

Burton, a chocolate labrador retriever, successfully recovered from intricate reconstructive facial surgery performed by Randy Boudrieau, DVM, DACVS, professor of Clinical Sciences at the Foster Hospital for Small Animals. Photo by Alonso Nichols, courtesy of Tufts University