Is that cat too fat? Feline obesity and a program for weight loss (Proceedings)

Obesity is the number one nutritional disorder in pets in the western world. Twenty five percent of cats seen by veterinarians in the USA and Canada are overweight or obese.

Obesity is the number one nutritional disorder in pets in the western world. Twenty five percent of cats seen by veterinarians in the USA and Canada are overweight or obese. Cats are no different than the rest of us, in that, over-consumption of calories results in storage and is manifested as excessive body fat. In optimal condition, cats should carry 15-20% body fat.

In 1998, Scarlett and Donoghue1 looked at diet and obesity in cats. Using multivariate statistical analysis controlled for age, they showed that obesity is a risk factor for diabetes mellitus, skin problems, hepatic lipidosis, and lameness. A more general look at the consequences of obesity or a chronic overweight state adds the additional risks in other species as well as the cat: hyperlipidemia, insulin resistance, glucose intolerance, feline lower urinary tract disease, anaesthetic complications, dyspnea, Pickwickian syndrome, exercise intolerance, heat intolerance, impaired immune function, exacerbation of degenerative joint disorders and dermatological conditions.

Interestingly, mixed breed cats were found to be at higher risk for becoming overweight than purebreds. This might be genetic, but husbandry and awareness of the cat may play a role. Because we confine cats indoors, feed them highly palatable, calorie-dense diets which they do not have to work for, and leave them alone many hours a day, possibly resulting in boredom, our cats are prone to consuming too many calories.

Neutering has been shown to reduce the energy requirements (resting metabolic rate) of cats by 20-25%.A link has been suggested between weight and fat gain following gonadectomy and serum leptin levels. It has also been shown that increased leptin levels may contribute to the decreased insulin sensitivity (resistance) seen in overweight cats. In fact, further work has indicated that insulin resistance and glucose intolerance develop in obese cats and that this occurs at an increased incidence in male cats; interestingly, male cats are at increased risk for developing diabetes mellitus.

It is important, therefore, that we counsel our clients to change to an adult formulation and to watch carefully for weight gain and adjust caloric intake accordingly. Ten extra pieces of an average formulation kibble/day above a cat's energy needs can result in a weight gain of one pound of body fat in one year!

Cats reach their adult weight at about 12 months of age. This can be used as a guide to determine if a cat is becoming overweight. As many of us know, it is easier to guard against weight gain than it is to lose weight.

The longer a cat (or person) is overweight, the greater the chance that one of the negative consequences of obesity will occur. This is similar to driving over the speed limit; the longer one does this, the greater likelihood of getting caught.

Uniquely feline

What specifics do we need to consider when addressing obesity because they are peculiar to cats? Cats weren't designed to utilize carbohydrates. As obligate carnivores, they have a smaller stomach and shorter intestinal tract relative to their body size when compared to omnivores or herbivores.

This is a reflection of their need for frequent meals. Their normal diet of small prey provides them with protein and fat. They lack glucokinase as a core enzyme in hepatic glucose metabolism. Of further note regarding the feline evolutionary disregard for carbohydrates, is the finding that cats lack salivary amylase and have only 5% of the pancreatic amylase activity and 10% of intestinal amylase activity of dogs.

Cats derive less energy per gram of carbohydrate than humans or dogs do. Cats have a vestigial cecum and a short colon which limits their ability to use poorly digestible starches and fibers through microbial fermentation seen in the large bowel of omnivores and herbivores.

This does not, however, imply that cats cannot use carbohydrates. They can use carbohydrates quite efficiently despite a lack of a dietary requirement for this energy source. Carbohydrates are a good energy source and have been shown to be necessary for lactating queens. If there is too much lactose or other sugars in the diet, then bloating, diarrhea and flatulence may result.

These points may be of clinical significance when considering the role that dry formulations (which contain more carbohydrate than other formulations) play in the way we feed cats. We really don't know what impact long term carbohydrate intake plays in predisposing cats to obesity and diabetes mellitus. Research out of Australia as well as the United States, The research is ongoing and hopefully we will have some answers in a few years.

Assessing Body Composition

It is easier to prevent weight gain than to lose weight. The prevalence of obesity increases after two years of age, plateaus until about 12 years and then declines thereafter.

What tools do we have to help prevent the development of obesity? At every veterinary visit, determining not only the patient's body weight and recording it in their medical record, but also calculating the percent weight change is an invaluable tool for the detection of weight change patterns. Many a cat with early chronic illness has been identified using this calculation: % weight change = (current weight – previous weight) / previous weight.

Use a body condition scale (BCS) at every visit, categorizing subjectively, the body condition as emaciated, thin, ideal, heavy or grossly obese (1-9 or 1-5 scale). This scale evaluates contours and silhouettes. In ideal condition, the bony prominences of the body (i.e. pelvis, ribs) can be readily palpated but not seen or felt above skin surfaces. There should be insufficient intra-abdominal fat to obscure or interfere with abdominal palpation.

By measuring lower leg length (middle of patella to point of hock) and rib cage circumference at widest point, a good assessment can be made of "feline body mass" to help determine if a cat is above or below normal body fat.

In questionable cases, radiographs and ultrasound may be used to assess falciform fat deposits, paralumbar and perirenal fat. In research settings, dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) evaluation is used for the most accurate bone density, muscle mass and fat calculations.

What To Feed

Simply feeding less of a normal diet is not recommended. Not only will the patient be unhappy and feel hungry, but nutritional balance will be compromised. A diet should be balanced according to energy content. When a cat eats enough of the diet to meet energy requirements, then their protein, vitamin and mineral needs will be met, as well. An energy-limiting diet is one, which is so energy dense that a cat will stop eating once energy needs have been met but before protein and other nutrient needs have been met. Similarly, a bulk-limiting diet will cause the individual to stop eating before energy and other nutrient needs have been met.

In cats, meeting protein needs, as well as energy needs induce satiety. During weight loss, feeding a protein replete diet will help protect against loss of lean muscle mass. For safe weight loss, cats need > 35% crude protein (dry matter basis), < 3.6 kcal metabolizable energy (dm basis), as well as 7-14% fat (dm basis).

When discussing with clients why reduced quantities of normal foods won't result in successful weight loss, the following may be considered:

• Normal diets are too high in fat.

• Fat is an easy energy source for manufacturing.

• There is less thermic energy formed in the digestion of fat.

• Digestibility is inversely proportional to the mount fed.

• All nutrients are decreased when you feed less of a balanced diet.

An individual's energy requirements are composed of several components. The daily energy requirement (DER) = resting energy requirement

+ exercise energy requirement

+ thermic effect of food (TEF)

+ adaptive thermogenesis (AT)

• Resting energy requirement varies with individuals; this accounts for the apparently higher manufacturer recommendations vs. a given individuals food needs.

• TEF is the energy spent on digesting and absorbing food. Increasing the frequency of meals and decreasing their size results in an increased TEF expenditure.

• AT is the energy used to regulate body temperature.

• DER decreases with increasing age.

A Clinic Weight Loss Program

In order to be successful with any weight loss program, three components must be in place: diet, exercise and recheck visits. Without any of these, the clients desire for their cat to slim down, will fail. A diet alone can't do it as recheck visits monitor progress and provide support needed by most people. Any exercise will help. We need to reduce the number of calories consumed, and increase calorie use and metabolic rate (exercise). Exercising cats could be seen as an oxymoron, however, some dedicated clients have even designed agility obstacle courses for their cats. Their commitment is the fuel for the success of the program.

On the initial extended consultation, a comprehensive physical exam is performed to rule-out concurrent medical problems. Baseline blood work may be advisable, depending on the age and condition of the kitty. A detailed history is collected in order to become familiar with current feeding habits and routines. Table 1 contains useful questions for this purpose.

Counsel the client to start a one-two week feeding journal in which everyone in the household who gives the cat anything ingestible, enters the information. The amount of food as well as exact type (brand) should be recorded. The client can be asked to make this diary before the appointment and bring it along. The diet diary provides the material needed to determine the caloric intake that the kitty has been receiving and gaining weight on. This should be compared to the caloric allowance being recommended. As a rule of thumb, in order to lose weight, a cat needs 60-70% of the calories required to maintain his/her ideal weight. In other words:

1. determine/approximate ideal weight

2. calculate calories needed for ideal weight (wt in kg X kcal/kg/day)

3. multiply this number by 60-70%.

Discuss with the client the benefits of weight loss as well as the risks of chronic obesity. Acknowledge them for their concern and praise them for their desire to take action. Be supportive! They are the ones who will have to do the work!

Inform them of the current weight as well as the goal weight. (The goal weight, may be higher than the "ideal" weight; the goal is a healthy weight, not a runway model.) Discuss with them the length of time this may take. A safe rate of weight loss is 1/4- 1/2 pound/month (0.1-0.25 kg/month). This will help them stay on track.

The thermic effect of food (TEF) is the energy cost of digesting and absorbing food. As mentioned above, the TEF is higher when small frequent meals are fed, so feeding multiple small meals is preferable to feeding one or two large meals. One way to incorporate this, as well as give the kitty a little challenge (and exercise), is to divide the day's food amount on to 6 or 7 small saucers and place them throughout the home as if it were a "treasure hunt". This means that kitty is less likely to gorge, has to look for more and has a higher TEF cost.

Discuss with the client why cats become overweight. The first thing to recognize is that pet food manufacturers have to make diets extremely palatable, because that is how a consumer judges how much their companion likes it and decides whether to buy it again or not. This means that most cat foods are very energy-dense from fat, as fat is palatable for cats. In addition, because it is convenient to feed ad libitum, cats snack all day on high calorie kibble, and easily eat more than they need. Cats generally lack exercise, when compared to the hunter that they are designed as. In the wild, they have to catch 10-20 small meals a day to survive! And, as already mentioned, an indoor environment is not very stimulating; cats may eat out of boredom. Former strays may also have the fear-driven instinct to gorge in case there isn't another meal.

The behaviour modification required to make a weight loss program successful, needs all key family members to play a role. Are there other forms of interaction that the client can have with the kitty, other than feeding? Treats are the downfall of many a weight control program. It is best if one person handles all of the feeding and others bond through other means (catnip, combing, playing). As mentioned earlier, feeding multiple small meals as a treasure hunt is beneficial. Developing a routine of playing with a "cat dancer" (a hand held flexible wire with a toy on the end) several times a day will add interest and exercise to the kitty's life. The cost of the program might include a bag of catnip and a cat dancer.

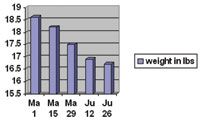

Create a bar graph to maintain in the clinic computer and kitty's medical record. Update and send the updated graph home with the client at every visit as a good reminder of their success.

Follow-up is the key to the success of any weight loss program! A technician or nurse (program supervisor) should become the client's "buddy" and be in charge of the follow-up.

No weight loss program is effective without follow-up!

• Week 1: support phone call

• Week 2: 15 minute visit with program supervisor and veterinarian:

• Weigh in (same scale)

• Conversation about highlights, problems

• Update graph

• Every 2 weeks come in for weigh-in.

• Update and send home graph.

• After 4 months, a 15-minute visit with the supervisor is advisable because a plateau may occur, and new calculations may be needed to promote further safe weight loss.

Included in the program cost is unlimited buddy phone support. The program lasts 6 months and is renewable if necessary.

Summary

Weight Loss Program

Initial 40-minute consultation with DVM: comprehensive physical examination to rule out medical problems

Evaluation of feeding diary (minimum 1 week feeding diary)

Evaluation of current feeding habits and routines

Diet history:

• Amounts and type of food (all, including treats)

• Milk?

• People food?

• Hunting?

• Who feeds the cat?

• Frequency of feeding?

• How is food measured?

• Medications?

• How are medications given? In food or with a treat?

• Does cat nibble or gorge?

• What other pets are there in the home?

• Do other pets have access to this food?

• Does this cat have access to their food?

• Where is cat fed?

• Is there any known stress?

• Activity level?

Calculate current caloric intake

Calculate recommended caloric intake: 60-70% of intake required for goal body weight (may need to use 50% if very inactive)

Send home a "weight loss pack" with food samples (dry and canned) for kitty to choose from.

Discuss

realistic goals

risks of obesity

why cats become overweight

behaviour modification

Follow-up!

• A technician or nurse should become the client's "buddy"& be in charge of the follow-up.

• No weight loss program is effective without follow-up!

• Week 1: support phone call

• Week 2: 15 minute visit with program supervisor:

• Weigh in (same scale)

• Conversation about highlights, problems

• Update graph

• Every 2 weeks come in for weigh-in

• Update and send home graph

• After 4 months, 15 minutes with supervisor as plateau may occur and new calculations may be needed to promote further safe weight loss

• Unlimited buddy phone support

• Program lasts 6 months and is renewable

References

Donoghue S, Scarlett JM: Diet and feline obesity. J Nutrition 1998; 128 (12 Suppl): pp 2776S-2778S.

Appleton DJ, Rand JS, Sunvold GD: Feline Obesity: Pathogenesis and Implications for the Risk of Diabetes, in Proceedings 2000 Iams Nutrition Symposium, pp 81-90.

Burkholder WJ, Toll PW: In Hand, MS, Thatcher, CD, Remillard, RL et al (ed): Small Animal Clinical Nutrition (4th ed). Topeka, Mark Morris Institute, 2000, pp 401-430.

Biourge, V: Feline Nutrition Update. World Small Animal Veterinary Association Congress, 2001.

Harper EJ, Stack DM, Watson TD, Moxham G: Effects of feeding regimens on bodyweight, composition and condition score in cats following ovariohysterectomy. J Small Anim Pract 42[9]: 433-8 2001

Martin L, Siliart B, Dumon H, Backus R, Biourge V, Nguyen P: Leptin, body fat content and energy expenditure in intact and gonadectomized adult cats: a preliminary study. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl) 85[7-8]: 195-9 2001

Appleton DJ, Rand JS, Sunvold GD: Plasma Leptin Concentrations Are Independently Associated with Insulin Sensitivity in Lean and Overweight Cats. J Feline Med Surg 4[2]: 83-93 2002

Chastain CB, Panciera D: Insulin Sensitivity Decreases with Obesity, and Lean Cats with Low Insulin Sensitivity Are At Greatest Risk of Glucose Intolerance with Weight Gain. Sm Anim Clin Endocrinol 12[2]: 9-10 2002 discussion of Appleton DJ, Rand JS, Sunvold GD: J Fel Med Surg 2001; 3:211-228

Michel, KE: Feline Nutrition: Fundamentals and Clinical Relevance. ABVP Symposium, 2002.

Michel, KE: Weight Reduction in Cats: Great Frustrations in Feline Nutrition. World Small Animal Veterinary Association Congress, 2001.