A challenging case: Abdominal effusion in a dog

Leakage of intestinal contents and a common contrast medium into a dog's abdominal cavity proved to be a fatal combination.

A 7-year-old 11.7-lb (5.3-kg) spayed female Cairn terrier was presented to the University of Florida Veterinary Medical Center for evaluation of pain on abdominal palpation and anorexia of four days' duration. Seven days before presentation, the patient had undergone a cystotomy for calcium oxalate urolith removal at a referring veterinarian's clinic. Two days before presentation, a gastrointestinal series had been performed at the same referring veterinary clinic for evaluation of abdominal pain and vomiting to rule out a gastrointestinal foreign body obstruction, but no abnormalities had been identified.

Vital Stats

INITIAL PRESENTATION AND EVALUATION

At presentation, the dog had normal vital signs but was lethargic with a tense abdomen and palpable abdominal fluid. The combination of the presenting signs with the history of a recent cystotomy raised suspicion for a possible uroabdomen secondary to surgical complications. An abdominocentesis yielded 12 ml of an opaque straw-colored fluid with a protein concentration of 3.2 g/dl, a red blood cell (RBC) count of 190/μl, and a white blood cell (WBC) count of 46,150/μl.

Cytologic examination

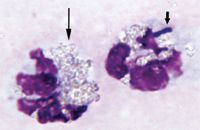

Cytologic examination of direct smears of the abdominal fluid revealed numerous cells and a pale basophilic granular background consistent with highly proteinaceous fluid. A 200 differential cell count yielded 99% neutrophils and 1% mononuclear phagocytes. The neutrophils were markedly karyolytic with occasional intracellular bacilli and numerous small, round-to-oval, pale-yellow refractile particles consistent with barium sulfate granules (Figure 1). The refractile material was also observed extracellularly in the background. The mononuclear phagocytes were moderately reactive. No neoplastic cells were identified. The cytologic interpretation was septic exudate containing material consistent with barium sulfate granules, suggesting leakage from the gastrointestinal tract.

Figure 1. Cytologic examination of abdominal fluid from the dog in this case reveals a neutrophil containing an intracellular bacterium (short arrow) and refractile granules of barium sulfate (long arrow). Barium sulfate granules are also noted in the background (Wright's-Giemsa; 100X).

Additional diagnostic tests

The complete blood count (CBC) results revealed a normal packed cell volume (PCV) of 45% (reference range = 37% to 54%) and a normal total WBC count of 14,230/μl (reference range = 6,000 to 17,000/μl) that was characterized by a mild left shift and 2+ toxic neutrophils. The serum chemistry profile revealed increased alkaline phosphatase (ALP) (496 U/L; reference range = 16 to 111 U/L) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (68 U/L; reference range = 10 to 46 U/L) activities and decreased concentrations of albumin (2 g/dl; reference range = 2.9 to 3.7 g/dl) and calcium (8.9 mg/dl; reference range = 9.5 to 11.6 mg/dl). The CBC results, increased liver enzyme activities, and decreased albumin concentration indicated active inflammation with possible infection. The hypocalcemia was attributed to the low albumin concentration.

Thoracic and abdominal radiographic examinations identified free barium in the abdomen and in the sternal lymph node, which supplies lymphatic drainage for the abdomen (Figure 2).

Figure 2. A right lateral thoracic radiograph of the dog reveals free contrast medium in the abdomen (short arrow) and contrast medium uptake in the sternal lymph node (long arrow).

Glucose concentrations measured in the serum (143 mg/dl; reference range = 70 to 122 mg/dl) and abdominal fluid (80 mg/dl) and lactate concentrations measured in the serum (2.1 mmol/L; reference range = 0.22 to 1.44 mmol/L) and abdominal fluid (6.1 mmol/L) were consistent with a septic peritoneal exudate. A difference of > 20 mg/dl between serum and abdominal fluid glucose concentrations and a difference of < -2 mmol/L between serum and abdominal fluid lactate concentrations are suggestive of a septic exudate in the abdomen.1 Consequently, a presumptive diagnosis of septic barium peritonitis secondary to gastrointestinal perforation, source unknown, was made.

Exploratory surgery

The dog was anesthetized, and an emergency exploratory laparotomy was performed. A copious amount of white-to-yellow purulent fluid was removed from the abdominal cavity. Adhesions were noted between the bladder and abdominal wall, between various loops of bowel, and between the bowel and bladder. A stick had penetrated the jejunal wall and entered the abdominal cavity. The stick was removed, and the affected regions of bowel were resected and anastomosed. The integrity of the anastomosis site was evaluated by intraluminal injection of sterile saline solution and found to be secure. The abdomen was thoroughly lavaged with warm sterile saline solution. A Jackson-Pratt closed suction drain was applied, and the patient recovered from anesthesia without complications. Aggressive postoperative antibiotic therapy and support measures were instituted.

Postoperative test results

During the next nine days, the patient exhibited slowly progressive lethargy and anorexia and started to again exhibit a tense abdomen. Bacterial culture of the original fluid obtained by abdominocentesis resulted in heavy growth of Escherichia coli.

Nine days after the surgery, the dog's temperature, and pulse and respiration rates were normal, but a CBC revealed a PCV of 32%, a fibrinogen concentration of 700 mg/dl (reference range = 100 to 400 mg/dl), and a total WBC count of 56,120/μl characterized by a neutrophilia with a marked left shift back to myelocytes with 2+ to 3+ toxic neutrophils. These CBC findings indicated a more dramatic response to the apparent infectious process. The serum chemistry profile revealed increased ALP (353 U/L) and AST (109 U/L) activities and total bilirubin concentration (12.1 mg/dl; reference range = 0 to 0.4 mg/dl) and decreased concentrations of albumin (1.8 g/dl) and calcium (8.7 mg/dl). The elevated bilirubin concentration was likely the result of functional cholestasis (sepsis-associated cholestasis). The hypocalcemia was again attributed to the low albumin concentration.

Outcome

Despite aggressive fluid and antibiotic therapy after the surgery, the dog developed acute vascular shock and cardiac arrest late on postoperative day 9. The patient was successfully resuscitated; however, it was euthanized a few hours later in accordance with the owner's wishes because of a poor prognosis, resulting from the clinical presumption of sepsis and suspected progression of the abdominal adhesions observed previously during surgery. A necropsy examination revealed evidence of leakage from the intestinal anastomosis site with diffuse peritonitis and adhesions in the cranial abdomen involving most of the small intestine and omentum.

DISCUSSION

Rapidly identifying barium sulfate free within a body cavity is essential in prompting emergency procedures that might prevent deleterious effects and, possibly, death. In this case, initial radiographic findings at the referring veterinary clinic did not indicate leakage of barium into the peritoneal cavity. This lack of noticeable leakage could be due to the possibility that the stick had not yet perforated the gastrointestinal tract.

Effects of barium sulfate suspension

Barium sulfate suspension in an animal's abdominal cavity causes a devastating peritonitis with mortality rates that rapidly increase in a quantity-dependent fashion.2-4 Barium sulfate quickly agglutinates and adheres to peritoneal surfaces.5 In experimental studies in dogs and rabbits, intraperitoneal barium sulfate suspension injections resulted in high mortality secondary to diffuse hemorrhagic peritonitis with numerous adhesions and granulomas throughout the abdominal cavity.3,4

When mixed with intestinal contents, barium sulfate has a synergistically deleterious effect—the intestinal contents and bacteria become trapped within granulomas that rapidly form in response to the barium sulfate.3,4 Visceral adhesions from fibrinous exudate form within six hours, and after three to five days, the barium sulfate becomes encapsulated within the fibrinous adhesions.5

In this case, marked fibrous adhesions developed throughout the mesentery and involved multiple bowel loops. Presumably, these adhesions caused delayed healing at the surgical anastomosis site and resulted in the leakage observed at necropsy.

Prevention and treatment

If contrast imaging is necessary in an animal with signs of peritonitis or if intestinal perforation is a differential diagnosis, it is best to use an iodinated contrast medium because of its lower propensity to incite peritoneal irritation. However, as seen in this case, sometimes perforations are not identified or suspected before contrast media administration.

Assuming barium sulfate was used in a gastrointestinal study, cytologic identification of this contrast media within an abdominal effusion confirms the leakage of gastrointestinal contents and should alert you to pending septic peritonitis. Since the combination of barium sulfate and intestinal contents free within the abdominal cavity results in time-dependent, synergistically deleterious effects, aggressive therapeutic treatment is warranted. More than routine abdominal lavage may be required to physically remove the contaminants, so gently rub the peritoneal surfaces with sterile gauze, and vigorously lavage the abdomen with warm sterile saline solution.

Even with rapid treatment, a patient's prognosis is guarded. However, prompt recognition and immediate treatment are essential in maximizing the chance of restoring health.6

Mark D. Dunbar, DVM

A. Rick Alleman, DVM, PhD, DABVP, DACVP

Department of Physiological Sciences

College of Veterinary Medicine

University of Florida

Gainesville, FL 32610

REFERENCES

1. Bonczynski JJ, Ludwig LL, Barton LJ, et al. Comparison of peritoneal fluid and peripheral blood pH, bicarbonate, glucose, and lactate concentration as a diagnostic tool for septic peritonitis in dogs and cats. Vet Surg 2003;32(2):161-166.

2. Henrich MH. [Barium peritonitis in animal experiments (rat, dog)]. Chirurg 1986;57(12):801-804. German.

3. Cochran DQ, Almond CH, Shucart WA. An experimental study of the effects of barium and intestinal contents on the peritoneal cavity. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med 1963;89:883-887.

4. Sisel RJ, Donovan AJ, Yellin AE. Experimental fecal peritonitis. Influence of barium sulfate or water-soluble radiographic contrast material on survival. Arch Surg 1972;104(6):765-768.

5. Thomas JC. The disposal of barium sulfate in the abdominal cavity. J Pathol Bacteriol 1936;43:285-298.

6. Gfeller RW, Sandors AD. Naproxen-associated duodenal ulcer complicated by perforation and bacteria- and barium sulfate-induced peritonitis in a dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1991;198(4):644-646.

Newsletter

From exam room tips to practice management insights, get trusted veterinary news delivered straight to your inbox—subscribe to dvm360.