A challenging case: A dog with intermittent pain and fever

A 2.5-year-old spayed female mixed-breed dog was presented to Claiborne Hill Veterinary Hospital for evaluation of a one-day history of pain when walking.

A 2.5-year-old spayed female mixed-breed dog was presented to Claiborne Hill Veterinary Hospital for evaluation of a one-day history of pain when walking. The dog's vaccination status was current. The patient had vomited in the car on the way to the hospital.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION FINDINGS AND INITIAL DIAGNOSTIC PROCEDURES

On physical examination, the patient weighed 43 lb (19.5 kg) and walked slowly. The dog's temperature was 102.4 F (39.1 C), heart rate was 128 beats/min, and respiratory rate was slightly elevated at 25 breaths/min. Its hydration status and mucous membrane color were normal. On palpation, pain was elicited along the lower abdomen but not along the dorsal or lateral aspect of the entire vertebral column.

Butorphanol tartrate (0.25 mg/kg subcutaneously) was administered for analgesia, and within a few minutes, the dog had a bowel movement consisting of firm stool followed by softer stool that contained mucus and blood. The results of fecal direct smear and simple flotation examinations were negative for parasites. The results of a urinalysis with sedimentation were normal. An abdominal radiographic examination revealed decreased serosal detail and fluid-filled bowel loops, without evidence of gastrointestinal obstruction. No other radiographic abnormalities were evident at this time.

An in-clinic complete blood count (CBC) revealed a marked leukocytosis with neutrophilia (Table 1) and increased platelets (523 × 109/L). An in-clinic serum chemistry profile revealed hypoalbuminemia (2.56 g/dl; reference range = 2.7 to 3.8 g/dl), hypoglycemia (60.2 mg/dl; reference range = 77 to 125 mg/dl), and a serum alkaline phosphatase activity of 212 U/L (reference range = 23 to 212 U/L).

Vital Stats

Within a relatively short period, the patient had a second bowel movement that consisted of bloody diarrhea. Our differential diagnoses at this time included sepsis, hemorrhagic gastroenteritis, and an unknown gastrointestinal disorder. Additional differential diagnoses include pancreatitis (the dog's amylase activity on presentation was 709 U/L; reference range = 500 to 1,500 U/L), peritonitis, hepatic abscess, stump pyometra, and acute abdomen. Other diagnostic tests, including abdominal ultrasonography and diagnostic peritoneal lavage, could have narrowed the list of differential diagnoses.

INITIAL TREATMENT

We initiated empirical treatment with intravenous lactated Ringer's solution with 5% dextrose (2.7 ml/kg/hour) and cefazolin (21.5 mg/kg b.i.d. slowly intravenously). We also administered ketoprofen (2 mg/kg given once intramuscularly) for its antipyretic and analgesic effects and oral metronidazole (13 mg/kg b.i.d.). Within a few hours, the patient appeared more comfortable, was wagging its tail, and had a heart rate of 100 beats/min.

On the morning of the second day of hospitalization, the dog was bright, alert, and responsive. Its rectal temperature was 102.4 F. We continued the intravenous fluids and cefazolin and oral metronidazole. The patient ate canned Purina Veterinary Diets EN (Nestlé Purina). But by late afternoon, the patient was reluctant to eat, cried when its abdomen was palpated, and vomited. We changed the fluid therapy to intravenous lactated Ringer's solution with potassium chloride (20 mEq potassium/L).

On the morning of Day 3, the patient was again bright, alert, and responsive. It had a rectal temperature of 102 F (38.9 C) and did not cry in pain but exhibited slight splinting during abdominal palpation. The dog urinated well and ate some of the canned diet. We continued the oral metronidazole, intravenous cefazolin, and fluid therapy.

A subsequent in-clinic CBC showed an elevated but slightly improved white blood cell count with neutrophilia (Table 1) and increased platelets (556 x 109/L). We initiated oral enrofloxacin therapy (7 mg/kg once a day) and continued to feed the canned diet, which the patient ate well.

On the morning of Day 4, the dog was bright, alert, and responsive and was eating dry Purina Pro Plan (Nestlé Purina). The dog's rectal temperature was 102.4 F. A follow-up abdominal radiographic examination revealed improved serosal detail, a large bladder, formed stool in the colon, and no obvious pattern of gastrointestinal obstruction. We discharged the patient with instructions to continue the metronidazole for 10 days and the enrofloxacin for nine days. We also instructed the owners to continue feeding the dry Pro-Plan diet and to return for a recheck in one week.

SECOND PRESENTATION

The following afternoon, the dog was presented to our hospital acutely stiff and in pain. Earlier in the day, the dog had been running with other dogs in the yard. In addition, the dog had produced a normal stool and had been eating and drinking normally. No vomiting or diarrhea had been noted. The owner had not given the metronidazole in the morning. On examination, the patient had a rectal temperature of 103.4 F (39.7 C). The dog's mucous membranes were pink, and its hydration was normal. The abdomen appeared slightly tense, and the dog walked with a slightly stiff gait.

The dog was hospitalized and was given ketoprofen (2 mg/kg intramuscularly). We continued the oral metronidazole and enrofloxacin.

The next morning (Day 6 since initial presentation), the dog was again bright, alert, and responsive and was walking well with no evidence of pain. The dog's rectal temperature was 100.6 F (38.1 C). We discharged the dog and continued the oral metronidazole and enrofloxacin therapy. In addition, we advised the owner to give half of a 325-mg buffered aspirin tablet once or twice a day as needed for pain.

The following week, the patient showed mild stiffness for two consecutive days (Days 9 and 10 after initial presentation), and the owner gave the dog buffered aspirin. On Day 12, the dog was bright, alert, and responsive and had a normal temperature. The results of a CBC showed an increased but improving total white blood cell count and neutrophilia. We advised a recheck examination in 10 days, and the metronidazole and enrofloxacin were continued for an additional 10 days.

Table 1 Patient Findings Throughout Treatment*

The dog became clinically normal after Day 25 with an improving white blood cell count beginning on Day 25, but a mild anemia was present for about one month before the dog relapsed on Day 43 (Table 1).

THIRD PRESENTATION

Forty-three days after the initial presentation, the dog was presented to our hospital for evaluation of an intense acute exacerbation of clinical signs. The owner stated that the dog seemed stiff without anti-inflammatory medication and that the dog's discomfort seemed to wax and wane over several days' time. The owner had given one 325-mg buffered aspirin tablet once a day for two consecutive days before presentation.

On physical examination, the patient had a rectal temperature of 103.2 F (39.6 C), moderate paraspinal pain, and mild ocular inflammation. The patient's weight was normal at 42.7 lb (19.4 kg). An in-clinic CBC showed marked leukocytosis with neutrophilia (Table 1).

We revised our differential diagnoses to include autoimmune, rickettsial, protozoal, and fungal diseases. We submitted blood samples to a diagnostic laboratory for a canine autoimmune profile, a CBC, and tick serology and initiated treatment with doxycycline hyclate (100 mg orally b.i.d.) for 14 days.

The CBC results showed marked leukocytosis with a mature neutrophilia (Table 1). In addition, lymphocytosis (6,286/μl; reference range = 690 to 4,500/μl), monocytosis (4,041/μl; reference range = 0 to 840/μl), and eosinophilia (1,347/μl; reference range = 0 to 1,200/μl) were present. The results of the direct Coombs', antinuclear antibody, and rheumatoid factor tests were negative. Antibodies against Ehrlichia canis and Borrelia burgdorferi were not detected. The Rickettsia rickettsii titer analyzed by immunofluorescent antibody (IFA) was 1:64, which indicated possible exposure or active infection. Because the results were negative with the exception of a low titer for R. rickettsii, we suspected hepatozoonosis and planned to perform a muscle biopsy if no improvement occurred with doxycycline therapy. Additionally, we dispensed deracoxib (50 mg orally once a day) as needed for pain. Within two days, the patient showed improvement with doxycycline and deracoxib.

DEFINITIVE DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

Two weeks later (55 days after the initial presentation), the dog was presented to our hospital for evaluation of acute stiffness and sensitivity to touch. The owner said the dog had been moping around and seemed feverish for several days. The patient had received doxycycline but had not received deracoxib for seven days.

On presentation, the patient had a rectal temperature of 101 F (38.3 C), weighed 42 lb (19.1 kg), and was sensitive over the cervical and lumbar spine as well as the right and left axial regions on deep palpation. Proglottids (Dipylidium caninum) were evident in the stool.

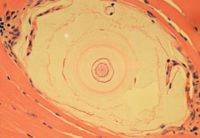

1. A photomicrograph of a skeletal muscle biopsy sample from this patient. There is a developing meront cyst within the host cell between muscle fibers (hematoxylin-eosin; 40X).

Because the dog had not improved with the doxycycline therapy, we proceeded with the muscle biopsy. The patient was sedated with medetomidine hydrochloride (0.5 ml intravenously) and butorphanol tartrate (0.15 mg/kg intravenously), was given carprofen (4.2 mg/kg subcutaneously), and was then prepared for surgery. Isoflurane anesthesia was available but not necessary in this case.

Four muscle biopsy samples were obtained by surgical excision—one each from the left biceps, right cervical (trapezius), and left and right epaxial (longissimus thoracis) areas. Because of the dog's nonresponsiveness to doxycycline and waxing and waning temperature and pain, we discontinued the doxycycline and initiated trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (25.2 mg/kg b.i.d. for 15 days), pyrimethamine (0.33 mg/kg [one-fourth of a 25-mg tablet] once a day for 15 days), and clindamycin (11 mg/kg t.i.d. for 15 days) to treat suspected hepatozoonosis.

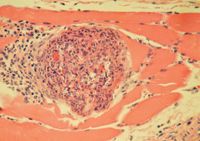

2. A photomicrograph of a skeletal muscle biopsy sample from this patient. Note the focal cluster of mixed mononuclear inflammatory cells, neutrophils, and some eosinophils associated with cystic rupture and necrotic myofibers (hematoxylin-eosin; 40X).

The next morning, the patient was bright, alert, responsive, and comfortable. We administered praziquantel (three 34-mg tablets orally) and discharged the patient.

Histologic examination of the muscle biopsy samples revealed protozoal cysts (Figure 1) and myositis (Figure 2) that were consistent with Hepatozoon species infection (Table 2).

The patient continued to receive trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, pyrimethamine, and clindamycin for a total of 14 days and was given deracoxib as needed for pain.

Table 2 Results of Histologic Examination of Skeletal Muscle Biopsy Samples*

About one week later (Day 70 after the initial presentation), the patient was clinically normal. We initiated treatment with decoquinate (Decox 6%—Alpharma) at a dose of 1 ¼ tsp once a day over food (¼ tsp/10 lb is approximately equal to 10 mg/kg, dosing for the highest 10-lb increment) and discontinued all other medications except for deracoxib as needed for pain.

FOLLOW-UP

Over the next five months, the owners reported that the dog had short, intermittent episodes of pain. We continued the decoquinate but switched the patient to carprofen (2.6 to 5.3 mg/kg orally daily as needed) for pain.

Five months later, about one year after the initial presentation (Day 367), the patient was presented to our hospital for evaluation of a recent history of episodes of pain and stiffness that were becoming more frequent. The owners gave the dog carprofen (5.3 mg/kg) the night before presentation. Physical examination findings were normal at this time.

The results of a CBC showed a mild leukocytosis with a mature neutrophilia (Table 1). A serum chemistry profile revealed mildly elevated aspartate transaminase (90 U/L; reference range = 15 to 66 U/L) and creatinine phosphokinase (987 U/L; reference range = 59 to 895 U/L) activities.

With the history and laboratory test results supportive of myositis secondary to parasitic reproduction, we increased the dosage of decoquinate to 2.5 tsp twice a day. Optimally, an additional two-week course of trimethoprim-sulfadiazine or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, pyrimethamine, and clindamycin should be administered to kill the merozoites in the tissues, as decoquinate functions mainly to arrest the developing zoites.1

Thirty-nine months after the initial diagnosis, the owners reported that the dog was stable, with minimal cyclic discomfort.

DISCUSSION

In the United States, hepatozoonosis is caused by Hepatozoon americanum, which is thought to be transmitted by the Gulf Coast tick Amblyomma maculatum,2 and infection results in a distinct clinical syndrome.3 In other parts of the world, Hepatozoon canis causes the disease, which is transmitted by the brown dog tick Rhipicephalus sanguineus, and the organism is much less virulent.3,4

Clinically, hepatozoonosis presents as a waxing, waning disease consisting of intermittent fever, chronic weight loss, mucopurulent ocular discharge, pain, muscle atrophy, and gait abnormalities (e.g. generalized stiffness, weakness, unwillingness to walk). The intermittent fever can reach as high as 106 F (41.1 C) and does not improve with antibiotic treatment. The pain is often intermittent and may be generalized, joint-associated, cervical, paraspinal, or abdominal.

In dogs with hepatozoonosis, a CBC often reveals a pronounced leukocytosis that is predominantly a mature neutrophilia. A mild nonregenerative anemia and elevated platelet counts may also be present. Thrombocytopenia is usually not evident unless the dog has concurrent ehrlichiosis, babesiosis, or Rocky Mountain spotted fever.3 A serum chemistry profile often reveals hypoalbuminemia, mild hypoglycemia, and mildly increased serum alkaline phosphatase activity.

Osteoproliferation is also associated with hepatozoonosis and is thought to be due to increased blood flow and fluid retention in the limbs, followed by proliferation of vascular connective tissue and periosteum and subsequent bone deposition.5 On radiographic examination, this is most frequently and most severely evident in the diaphyses of long bones and, to a lesser extent, in flat and irregular bones5 such as vertebrae or the pelvis.2,3 These lesions are proliferative, can be subtle or obvious, and may consist of smooth lamellar periosteal thickening or irregular proliferative exostoses.3 Pronounced neutrophilia in combination with periosteal proliferation may be highly indicative of American canine hepatozoonosis.2,3 However, in this case, the initial radiographs of the caudal thoracic, abdominal, and cranial pelvic areas obtained on presentation did not show evidence of these lesions.

Follow-up pelvic and hindlimb long bone radiographs taken 19 months after initial presentation showed subtle evidence of periosteal proliferation on the pelvis, which became more pronounced over the following two months.

For definitive diagnosis of canine hepatozoonosis, the parasites must be detected on cytologic or histologic examination. Examination of blood smears may reveal the gametocytes within the cytoplasm of leukocytes as 11-x-5-μm oblong inclusion bodies with clear or pale-blue capsules.3 Recent studies have identified both merozoites and gamonts in circulating macrophages.4 But often only a few white blood cells (about 0.1%) are infected. In addition, the parasites' nuclei stain poorly, and the parasites may leave the cells once the blood sample is collected, so only empty capsules remain. Thus, skeletal muscle biopsy is often indicated for definitive diagnosis, and histologic examination reveals meront cysts, merozoites, or pyogranulomas among the muscle cells.3

Hepatozoon americanum infection in dogs is most common where A. maculatum, resides—primarily the Gulf Coast states. Hepatozoon americanum needs two hosts to complete its life cycle, and A. maculatum is thought to be the definitive host. Dogs are the intermediate host; there have been reports of the disease in dogs in Texas, Oklahoma, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, and Florida.1,2 When the ticks feed on infected dogs, they ingest gametocytes. In the tick, these gametocytes fuse into an ookinete. The ookinete becomes an oocyst consisting of many sporocysts, each of which contains 12 to 24 sporozoites.3 Dogs become infected by ingesting the ticks, likely through grooming, rather than by being bitten by the tick.1 Hundreds of sporozoites can then penetrate the dog's gastrointestinal tract and circulate through the blood or lymphatic system.1,3

To continue their life cycle, the sporozoites enter macrophages4 where they are protected and intracellular merogony (asexual reproduction) may occur.1 When a meront ruptures and the cyst wall disintegrates, the area becomes inflamed and angiogenesis occurs.1 Zoites that have been phagocytized enter the bloodstream through these vessel walls and may either circulate as gamonts, which ticks can ingest while feeding on the dog, or become merozoites, which repeat the asexual reproduction life cycle within the dog. Thus, a dog that ingests a single infected tick can have a prolonged waxing and waning illness associated with the repeated asexual reproduction cycles of the organism.1

Cysts are the stage most likely to be seen in dogs. The 250- to 500-μm-diameter, round-to-ovoid cysts have pale-blue laminar membranes and resemble an onion skin.3 These cysts are usually found in cardiac and skeletal muscle, lymph nodes, the spleen, and the pancreas.3 Long-term complications may include vascular thrombosis; interstitial nephritis; glomerulonephritis; nephrotic syndrome; amyloid deposits in the spleen, lymph nodes, small intestines, liver, and kidneys; and hypercoagulability.2,3

Initially, treatment is empirical depending on the presenting signs. Often, doxycycline (5 mg/kg once a day for 14 days) is initiated to treat for other possible concomitant tick-borne diseases. No definitive treatment reliably eliminates H. americanum in dogs. Initially, the signs may subside with a two-week course of trimethoprim-sulfadiazine1,2 or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (15 mg/kg orally b.i.d.), pyrimethamine (0.25 mg/kg orally once a day), and clindamycin (10 mg/kg orally t.i.d.) along with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for fever and pain. Many dogs relapse within six months, possibly because of cyst rupture and release of merozoites with resulting secondary pyogranulomatous inflammation.

Administering decoquinate (10 to 20 mg/kg orally b.i.d.) for at least two years may extend remission.1-3 Optimally, any patient that relapses should be treated with a two-week course of trimethoprim-sulfadiazine1 or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, pyrimethamine, and clindamycin, and the dosage of decoquinate should be increased simultaneously to the upper dosage limits.

A recent study has shown a high relapse rate: 12 of 27 dogs treated long-term, with eight of the 27 relapsing more than once.1 Four of the 27 dogs relapsed within one or two weeks of missing doses of decoquinate. None of the dogs that were treated long-term in this study developed proteinuria, muscle wasting, severe cachexia, or evidence of renal disease.1 Decoquinate inhibits the organism's asexual reproduction cycles and subsequent release of zoites, which stops the pyogranulomatous inflammation and sequelae. Mean survival times that were previously estimated at 10 to 12 months2,3 were greater than 39 months for 22 of the 27 dogs; in 11 of these 22 dogs, the decoquinate was discontinued after a mean treatment time of 13.7 ± 6 months. The remaining 11 continued to receive decoquinate with a mean treatment time of 20 ± 8 months.1

In that study, 84% of dogs treated with trimethoprim-sulfadiazine, pyrimethamine, and clindamycin followed by decoquinate had a mean survival time of greater than two years. Further long-term studies are needed to determine mean survival times, as 22 of 27 dogs were still alive when the study was published.1

Michael G. Strain, DVM

Tommi A. Pugh, DVM

Claiborne Hill Veterinary Hospital

19607 Highway 36

Covington, LA 70433

REFERENCES

1. Macintire DK, Vincent-Johnson NA, Kane CW, et al. Treatment of dogs infected with Hepatozoon americanum: 53 cases (1989-1998). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2001;218:77-82.

2. Keller RL, Lurye J. What is your diagnosis? J Am Vet Med Assoc 2004;225:1531-1532.

3. Macintire DK, Vincent-Johnson N. Canine hepatozoonosis. In: Bonagura JD, ed. Kirk's current veterinary therapy XIII small animal practice. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders Co, 2000;310-313.

4. Cummings CA, Panciera RJ, Kocan KM, et al. Characterization of stages of Hepatozoon americanum and of parasitized canine host cells. Vet Pathol 2005;42:788-796.

5. Panciera RJ, Mathew JS, Ewing SA, et al. Skeletal lesions of canine hepatozoonosis caused by Hepatozoon americanum. Vet Pathol 2000;37:225-230.