A challenging case: A febrile dog with a swollen tarsus and multiple skin lesions

A 9-month-old neutered male Labrador retriever was referred to the Small Animal Teaching Hospital of the University of Prince Edward Island for evaluation of a one-week history of pyrexia, a markedly swollen right tarsus, pronounced submandibular lymphadenopathy, and progressive pustular to erosive, nonpruritic, crusting skin lesions.

A 9-month-old neutered male Labrador retriever was referred to the Small Animal Teaching Hospital of the University of Prince Edward Island for evaluation of a one-week history of pyrexia, a markedly swollen right tarsus, pronounced submandibular lymphadenopathy, and progressive pustular to erosive, nonpruritic, crusting skin lesions. A week before referral, the owner had first noticed an enlarged left submandibular lymph node and a pustule on the lip. When the dog had been presented to the referring veterinarian the following day, it had been febrile (104.9 F [40.5 C]) and nonweightbearing on its right hindlimb because of a swollen and painful right tarsus. Pustular lesions had erupted over its nose and ears.

1A & 1B. The distribution of pustular skin lesions on the face of the dog in this case.

The results of a complete blood count had revealed a slight monocytosis, and the results of a serum chemistry profile and urinalysis had been unremarkable. Radiographic examination of the right hock had revealed soft tissue swelling. In-house cytologic examination of joint fluid from the right tarsus had revealed no etiologic agents. The referring veterinarian had treated the dog with intravenous fluids, antibiotics (ampicillin 18 mg/kg intravenously b.i.d.; trimethoprim-sulfadiazine 30 mg/kg once a day; and cefoxitin sodium 18 mg/kg intravenously b.i.d.), and a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agent (flunixin meglumine 1 mg/kg orally once a day). The dog's condition had not changed over the next four days except for a temporary resolution of its fever. The day before referral, the veterinarian had administered a single dose of prednisone (2 mg/kg orally). The dog's vaccination status was current, and the dog had no history of travel outside of Nova Scotia.

2. Pustular and secondary erosive ulcerative lesions on the inner pinna and in the external auditory meatus.

Physical examination and differential diagnoses

On physical examination, the dog was in fair body condition and weighed 60.3 lb (27.4 kg), but it was depressed, febrile (103.1 F [39.5 C]), and tachypneic (60 breaths/min). The dog had tacky mucous membranes and was estimated to be 5% dehydrated. We noted pustular lesions on the concave aspect of both pinnae, in the external auditory canals, on the muzzle and chin, around the eyes, and on the prepuce (Figures 1-3). Many of the pustules had ruptured and were oozing serosanguineous discharge. A serous bilateral ocular discharge and depigmentation of the nasal planum were evident. The dog's prepuce was swollen, with ulcerative lesions at the mucocutaneous junction (Figure 3). Both submandibular lymph nodes were markedly enlarged, and the prescapular lymph nodes were mildly enlarged. Multiple freely movable, mildly painful, fluctuant, subcutaneous nodules ranging in size from 1 to 2 cm in diameter were palpable on both sides of the dog's thorax. The dog was nonweightbearing on its right hindlimb because of a markedly swollen, painful, and warm right tarsus. All remaining joints were clinically normal.

3. Pustular and secondary erosive lesions on the dog's prepuce.

Our differential diagnoses for the dermatologic lesions included systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), pemphigus complex, demodicosis with furunculosis and secondary bacterial pyoderma, folliculitis or furunculosis secondary to a staphylococcal dermatitis, dermatophytosis, erythema multiforme, toxic epidermal necrolysis, and canine juvenile cellulitis. We considered a drug eruption less likely because there was no known history of drug therapy before the lesions appeared. Our differential diagnoses for the acute-onset right tarsal joint effusion included an infectious arthritis, an immune-mediated arthritis (erosive or nonerosive), and degenerative joint disease secondary to unknown trauma. Our differential diagnoses for the multiple subcutaneous nodular lesions included infection (e.g. bacterial, fungal, parasitic, protozoal), sterile inflammatory disorders (e.g. nodular panniculitis, sterile granuloma or pyogranuloma syndrome, reactive systemic histiocytosis, xanthomas, canine juvenile cellulitis), and, less likely, neoplasia. We attributed the dog's tachypnea to pain and the fever, and we attributed the nasal planum depigmentation to irritation from the serosanguineous discharge from the skin lesions.

Vital Stats

Initial diagnostic tests

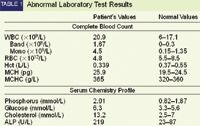

The dog was hospitalized, and we performed a complete blood count (CBC), serum chemistry profile, and urinalysis. The abnormal results of the CBC (Table 1) revealed leukocytosis with a regenerative left shift, 1+ toxic change, and monocytosis. These changes were consistent with chronic active inflammation. We interpreted a nonregenerative, macrocytic, hyperchromic anemia as an anemia of chronic disease with artifactual increases in mean corpuscular hemoglobin and mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration from in vitro hemolysis.

The abnormal results of the serum chemistry profile (Table 1) revealed mild hyperphosphatemia, hyperglycemia, hypercholesterolemia, and a mild increase in alkaline phosphatase activity. We attributed the elevated phosphorus concentration and alkaline phosphatase activity to physiologic increases associated with growth. We attributed the hyperglycemia to stress and the moderate hypercholesterolemia to a postprandial increase.

Abnormal Laboratory Test Results

The results of urinalysis (sample collected by cystocentesis) revealed a slightly low urine specific gravity (1.020), hematuria (80 to 100 RBC/hpf) and trace proteinuria. The hematuria was iatrogenic, and the results of a urine protein:creatinine ratio to quantify the proteinuria and rule out concurrent glomerulonephritis were normal (0.43, reference range < 1). Serum was also submitted for an antinuclear antibody titer.

Treatment and further tests

On Day 1, we initiated intravenous fluids (Plasmalyte 148 [Baxter] with 16 mEq/L potassium chloride added), morphine sulfate (0.2 mg/kg subcutaneously q.i.d.), and cephalexin (22 mg/kg orally b.i.d.) as prophylaxis for secondary bacterial skin infections.

On Day 2, the dog remained febrile, and inguinal lymph node enlargement and additional truncal subcutaneous masses had developed. The dog was anesthetized and prepared for arthrocentesis of multiple joints, including the right tarsal joint. We performed arthrocentesis of the right stifle, right carpus, and both tarsi. The synovial fluid was grossly normal from all joints except the right tarsus. The synovial fluid from the right tarsus was serosanguineous and had decreased viscosity. This joint had been aspirated by the referring veterinarian five days before, so we suspected secondary iatrogenic blood contamination.

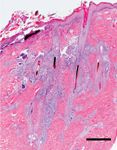

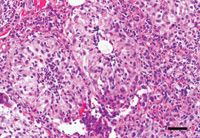

4. A photomicrograph of the dog's skin showing multifocal to coalescing pyogranulomatous inflammation surrounding several follicles (hematoxylin-eosin; bar = 500 µm).

While the dog was anesthetized, we obtained multiple representative full-thickness 4-mm punch biopsy samples of abnormal tissue from the periocular region, muzzle, chin, inner pinnae, prepuce, and truncal skin for histologic examination. The enlarged lymph nodes and truncal subcutaneous masses were also aspirated for cytologic evaluation. Grossly, the aspirate of the right submandibular lymph node appeared abnormal, consisting of serosanguineous fluid. The referring veterinarian had previously aspirated this lymph node and noted an increase in plasma cells and lymphoblasts.

We also obtained multiple deep skin scrapings of the lesions and normal areas of skin while the dog was anesthetized, and microscopic examination failed to reveal ectodermal parasites, making demodicosis unlikely. Cytologic examination of an impression smear from an intact pustule showed mixed inflammation with nondegenerate neutrophils and macrophages. Cytologic examination of the impression smears of the draining lesions on the face and prepuce also showed mixed inflammation with nondegenerate neutrophils and macrophages. No infectious agents were seen in any of the samples examined cytologically.

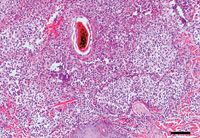

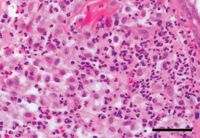

5. A photomicrograph of the dog's skin showing perifollicular pyogranulomatous inflammation surrounding and effacing sebaceous and sweat glands (hematoxylin-eosin; bar = 100 µm).

The findings from the cytologic examination of aspirates from the prescapular and submandibular lymph nodes and the truncal masses were consistent with pyogranulomatous inflammation. The submandibular lymph nodes also contained epithelioid macrophages. The findings from the cytologic examination of the inguinal lymph node aspirates were consistent with reactive lymphoid hyperplasia. No infectious agents were seen.

Cytologic analysis of the joint fluid revealed that the right carpus was normal; the right tarsus showed neutrophilic inflammation, the left tarsus showed mononuclear inflammation, and the right stifle showed mixed mononuclear and neutrophilic inflammation. No infectious agents were seen in any of the joint fluid samples. No growth occurred on an aerobic bacterial culture of the right tarsal joint fluid, making septic arthritis less likely. The results of aerobic bacterial cultures of fluid from the right submandibular lymph node and fluid from one of the skin pustules were negative, making staphylococcal dermatitis less likely. No infectious agents were seen after Gram's and acid-fast staining in any of the samples submitted for culture.

On Day 2, we initiated an immunosuppressive dosage of prednisone (1 mg/kg orally b.i.d.) because we suspected an immune-mediated disorder. On Day 3, the dog developed mucopurulent ocular discharge. The results of a complete ophthalmic examination were normal except for bilateral conjunctivitis, likely secondary to irritation from periocular skin disease. We prescribed a bacitracin/neomycin/polymyxin B/hydrocortisone ophthalmic ointment (topically to both eyes t.i.d.). On Day 4, the dog was clinically much brighter and no longer febrile, so we discontinued intravenous fluids. We discontinued the morphine on Day 5. For the first two days in the hospital, the dog was anorectic and showed no interest in food, but by Day 6, the dog was eating well.

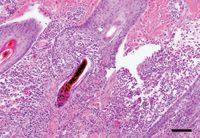

6. A photomicrograph of the dog's skin showing inflammation surrounding and infiltrating hair follicles, leading to rupture of the follicles (hematoxylin-eosin; bar = 100 µm).

Histologic results and diagnosis

The results of the histologic examination of the skin biopsy samples revealed inflammatory nodular dermal infiltrates that centered around hair follicles and often partially or completely effaced the associated sebaceous and sweat glands (Figures 4 & 5). In some areas, the follicles had ruptured (Figure 6). The inflammatory infiltrates were composed mainly of neutrophils and epithelioid macrophages with smaller numbers of plasma cells and lymphocytes (Figures 7 & 8).

The histopathologic diagnosis was nodular pyogranulomatous dermatitis with folliculitis and furunculosis. Unfortunately, none of the skin biopsy samples included the subcutis, so the presence of nodular sterile panniculitis could not be conclusively confirmed. But the cytologic findings from these subcutaneous nodules were supportive of this presumptive diagnosis. No evidence of an interface dermatitis or any other epidermal abnormalities characteristic of SLE was present. In addition, the results of the ANA titer were negative, making SLE less likely; however, some dogs with SLE have negative ANA titer results, so the titer results alone cannot be used to conclusively rule out SLE. We ruled out pemphigus complex because no evidence of subcorneal or intragranular pustules or suprabasilar vesicles with acantholysis was present. Likewise, the histopathologic lesions were not consistent with erythema multiforme or toxic epidermal necrolysis, which typically result in epidermal lesions. A primary staphylococcal folliculitis or furunculosis seemed unlikely because of the systemic nature of the disease, the lack of cocci bacteria in any of the samples, and the negative bacterial culture results from the skin. The histologic findings and the clinical signs (cutaneous and systemic) most closely fit with a diagnosis of late-onset canine juvenile cellulitis.

7. A photomicrograph of the dog's skin at higher magnification showing some well-delineated granuloma-like lesions. (hematoxylin-eosin; bar = 50 µm).

Follow-up

The dog was discharged on Day 6. At this time, the dog was alert, the preputial swelling had resolved, and the facial pustules had decreased in number and were no longer rupturing. The prescapular lymph nodes were smaller, but there was no appreciable change in the size of the submandibular and inguinal lymph nodes. Evidence of panniculitis was still present, but the right tarsal swelling and lameness had resolved. The dog continued to receive the cephalexin, prednisone, and ophthalmic ointment at the previously stated doses for 10 days. At a 10-day recheck performed by the referring veterinarian, the dog's lesions were dramatically improved, so the cephalexin and ophthalmic ointment were discontinued, and the owners were instructed to slowly taper the prednisone over the next six to eight weeks (i.e. a 25% reduction in the dose every two weeks). Eight weeks after presentation, the dog's skin lesions had completely resolved.

Discussion

Juvenile cellulitis, also referred to as juvenile pyoderma, puppy strangles, and juvenile sterile granulomatous dermatitis and lymphadenitis, is an uncommon disorder primarily reported in puppies between 3 and 12 weeks of age.1 Often, more than one puppy in a litter is affected. The condition has been reported sporadically in many breeds, but golden retrievers, dachshunds, and Gordon setters may be predisposed.1,2 The development of the dermatologic lesions is often preceded by an acute onset of facial swelling with markedly enlarged submandibular lymph nodes.1 This is followed by the rapid development of papules and pustules affecting the face, pinnae, lips, and periocular region. Pustules typically rupture and eventually crust over. A marked painful, pustular otitis externa may also occur.1,3,4 The reactive submandibular lymphadenopathy that often precedes the development of the dermatologic lesions is pronounced, and the lymph nodes may eventually rupture (as likely would have happened in this case) and become fistulous.1

8. A photomicrograph of Figure 7 at a higher magnification showing predominantly epithelioid macrophages and neutrophils (hematoxylin-eosin; bar = 50 µm).

The reactive lymphadenopathy may also be more generalized, as seen in this patient. Half of all affected puppies exhibit lethargy, and 25% are systemically ill, exhibiting anorexia, pyrexia, and joint pain.1,3 The arthritis is characterized by a sterile suppurative reaction.3 Rarely, a sterile pyogranulomatous panniculitis with painful, firm to fluctuant, subcutaneous nodules most commonly occurring on the trunk or in the preputial or perianal region is reported (as was presumptively diagnosed in this patient, based on the cytology results and response to immunosuppression). These nodules may become fistulous, leaving deep draining tracts. In two Shetland sheepdog puppies with juvenile cellulitis, including panniculitis, neurologic signs consistent with spinal cord lesions were also seen.1 Concurrent hypertrophic osteodystrophy has also been reported in three dogs, all of which had been inoculated with a combination vaccine containing live attenuated canine distemper virus 10 to 14 days before the clinical signs developed.5 The authors of this report speculated that in some patients juvenile cellulitis might be an atypical clinical variant of canine distemper virus infection.6 The dog in this report had not received a vaccination in over three months.5 Unfortunately, radiographic examination of this dog's right tarsus was not done to rule out concurrent hypertrophic osteodystrophy.

This case was interesting not only because of the unusual late onset of the condition but also because of the severe systemic manifestations. There is only one other report in the veterinary literature of juvenile cellulitis in an older dog, a 2-year-old Lhasa apso.4 Also, although other cases of systemic involvement (e.g. concurrent arthritis and panniculitis) have been reported,3 it is not typical for dogs to display all the systemic clinical features seen in this case.

Diagnosing juvenile cellulitis relies on support from the history, clinical findings, and results of cytologic examination, culture, and, most importantly, histologic examination. Cytologic examination of pustular lesions reveals pyogranulomatous inflammation with no infectious agents.1,3,6 The results of cultures of the pustules are expected to be negative. Skin biopsy samples demonstrate granulomatous to pyogranulomatous inflammation consisting of clusters of large epithelioid macrophages and neutrophils. As the inflammation progresses, adnexal glands (e.g. sebaceous and sweat glands) may be effaced, and suppurative changes in the superficial dermis with folliculitis and furunculosis may develop (as seen in this case). Focal to coalescing suppurative inflammation may also develop in the subcutis, resulting in panniculitis.1,6

The underlying cause and pathogenesis of juvenile cellulitis is unknown. Heritability is thought to play a role because of the predisposition of certain breeds and the familial association of the disease.1 Proposed causes include infectious, immunologic, and hypersensitivity reactions. In addition, trauma, endoparasitism, diet, and environmental triggers have all been proposed as possible causes, but no evidence is available to support these theories.4 Detection of infectious agents with special staining techniques, culturing, electron microscopic examination, and other diagnostic tools has not been successful. The inoculation of lymph node tissue from affected dogs into newborn puppies has failed to transmit the disease.6 Because of this lack of transmission and the typical dramatic response to immunosuppressive doses of glucocorticoids, it is unlikely an unidentified infectious agent is responsible.

An immune system deficiency has also been proposed, but several studies that attempted to investigate this by immunoglobulin concentration quantification, serum electrophoresis, and other methods failed to demonstrate any such deficiency.6,7 Although it has also been proposed that juvenile cellulitis may represent a hypersensitivity, such as an autoimmune or an allergic skin disease, juvenile cellulitis does not require long-term immunosuppression with glucocorticoid therapy or allergen elimination, respectively.4 Treating juvenile cellulitis requires early and aggressive immunosuppression with glucocorticoids until the disease is no longer active and then gradually tapering the medication. Typically, prednisone or prednisolone (2 mg/kg orally once a day) is administered for 14 to 21 days. Patients that have truncal panniculitis may require a longer course to resolve all lesions. As with other immune-mediated diseases, some dogs respond better to an alternative glucocorticoid, such as dexamethasone (0.2 mg/kg orally once a day). Concurrently administering a bactericidal antibiotic (e.g. cephalexin, amoxicillin trihydrate-clavulanate potassium) is indicated if there is cytologic or clinical evidence of secondary bacterial infection. Relapses are extremely rare.1

The dog in this case closely followed the typical clinical course expected with a case of juvenile cellulitis, but the case emphasizes that severe systemic involvement can occur and that juvenile cellulitis should be a differential diagnosis in dogs presenting with pustular dermatitis and lymphadenopathy, even in those older than 12 weeks of age.

Elisabeth C. Snead, DVM*

Carrie Lavers, DVM**

Department of Small Animal Internal Medicine

Atlantic Veterinary College

University of Prince Edward Island

Charlottetown, PEI C1A 4P3

Paul Hanna, DVM, MSc, DACVP

Department of Pathology and Microbiology

Atlantic Veterinary College

University of Prince Edward Island

Charlottetown, PEI C1A 4P3

Current addresses:

*Department of Small Animal Clinical Sciences

Western College of Veterinary Medicine

University of Saskatchewan

Saskatoon, SK S7N 5B4

**Animal Health Center

Box 1650

Swift Current, SK S9H 4G6

REFERENCES

1. Scott, D.W. et al.: Miscellaneous skin diseases. Muller & Kirk's Small Animal Dermatology, 6th Ed. W.B. Saunders, Philadelphia, Pa., 2001; pp 1163-1167.

2. Mason, I.S.; Jones, J.: Juvenile cellulitis in Gordon setters. Vet. Rec. 124 (24):642; 1989.

3. White, S.D. et al.: Juvenile cellulitis in dogs: 15 cases (1979-1988). JAVMA 195 (11):1609-1611; 1989.

4. Jeffers, J.G. et al.: A dermatosis resembling juvenile cellulitis in an adult dog. JAAHA 31 (3):204-208; 1995.

5. Malik, R. et al.: Concurrent juvenile cellulitis and metaphyseal osteopathy: An atypical canine distemper virus syndrome? Aust. Vet. Pract. 25:62-67; 1995.

6. Reimann, K.A. et al.: Clinicopathologic characterization of canine juvenile cellulitis. Vet. Pathol. 26 (6):499-504; 1989.

7. Barta, O.; Oyekan, P.P.: Lymphocyte transformation test in veterinary clinical immunology. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 4 (2):209-221; 1981.