Clinical Exposures: Palpebral reconstruction after entropion surgery in a dog

A 9-year-old 46.2-lb (21-kg) spayed female mixed-breed dog was presented to the ophthalmology service at Colorado State University for evaluation of incisional infection and delayed healing after bilateral entropion surgery.

A 9-year-old 46.2-lb (21-kg) spayed female mixed-breed dog was presented to the ophthalmology service at Colorado State University (CSU) for evaluation of incisional infection and delayed healing after bilateral entropion surgery.

HISTORY

The dog received a dental prophylaxis at its regular veterinarian's clinic nine days before presentation. While the dog was anesthetized, the veterinarian also performed bilateral blepharoplasties on the upper and lower eyelids. The dog recovered uneventfully, but a day after the surgery, it exhibited epiphora and blepharospasm and frequently vocalized.

The dog had been taken to an emergency clinic, and the emergency veterinarian prescribed a five-day course of tramadol for pain. The dog failed to improve and was re-presented to its regular veterinarian two days later. The veterinarian told the owner that the dog was progressing normally; however, the owner disagreed because the dog still had severe blepharospasm and had developed a greenish-yellow ocular discharge.

The owner had then taken the dog to a veterinary ophthalmologist for a second opinion. The ophthalmologist diagnosed septic blepharitis and removed the sutures to allow for better infection resolution and for second intention healing. In addition, the dog had received cephalexin (500 mg every eight hours) and triple antibiotic ophthalmic ointment (every eight hours in both eyes). The dog did not improve rapidly, so three days later it was presented to CSU.

PHYSICAL AND OPHTHALMIC EXAMINATION FINDINGS

A complete physical examination revealed that the abnormalities were confined to the dog's eyelids and eyes. Partially healed incisions extended the entire length of the upper and lower eyelids bilaterally.

On the left side, the incisions in the medial canthus and central part of the lower eyelid had pulled apart, and the subcutaneous tissue was exposed. The remainder of the left lower eyelid and the full length of the upper eyelid contained excessive granulation tissue. The right side appeared similar to the left, but no lesions were present at the medial canthus. In both eyes, short, abnormally directed cilia on both the upper and lower eyelids were growing toward and rubbing on the corneas. The initial incisions had split the eyelid margins just anterior to the meibomian glands, which resulted in eyelid thinning and contraction and exposure of the eyelash roots, causing them to grow abnormally (Figures 1 & 2). The conjunctivas were inflamed and the globes were retracted, leading to protrusion of the nictitating membranes.

1. The dog's left eye before reconstructive surgery. The medial canthus is on the left, and the nictitating membrane is elevated. Note the dehisced area at the medial canthus and inferior eyelid, the abnormal cilia (white arrow), and the excessive fibrous tissue (blue arrow).

All other ophthalmic examination results were normal. The Schirmer tear test values were > 15 mm/30 sec in both eyes (normal > 15 mm/min). Intraocular pressures were 20 mm Hg in the right eye and 15 mm Hg in the left eye (normal = 15 to 20 mm Hg), and there was no fluorescein stain uptake.

2. The dog's right eye before reconstructive surgery. The medial canthus is on the right. Note the scar tissue, which had led to the rolling in of the lower eyelid at the lateral canthus. The dog was anesthetized, so the eyelids were relaxed and the entropion cannot be appreciated as well.

PROBLEM LIST

The problem list included delayed healing of the eyelid incision sites due to infection and premature suture removal, excessive granulation tissue formation at the palpebral margins, misdirected cilia (iatrogenic distichiasis), conjunctivitis, and infectious blepharitis. The mechanical nature of these problems precluded resolution by medical therapy, so surgical intervention was necessary to remove the scar tissue and abnormal cilia and to reconstruct the eyelid margins to be as functionally normal and cosmetically acceptable as possible.

SURGERY

Anesthesia and surgery were performed a day after presentation. The area around both eyes was minimally clipped, and ophthalmic ointment (Puralube—Fougera) was applied to both eyes. The dog was placed in right lateral recumbency, and the skin around the eyes was aseptically prepared by gently scrubbing it with cotton balls containing dilute baby shampoo (1:2) and alternating three times with dilute povidone-iodine solution (1:50) rinses.

3. Incisions were made on the upper and lower right eyelids to remove the fibrous tissue and cilia, and the incision edges were apposed and sutured in a manner similar to that on the left side.

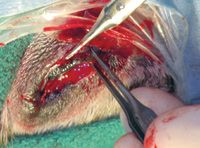

An incision was made with a No. 10 Bard-Parker scalpel blade in the left lower eyelid skin just ventral to the granulation tissue. The incision extended from the most medial aspect of the tissue to the lateral canthus. Ophthalmic tenotomy scissors were used to dissect under and remove the granulation tissue from the palpebral margins (Figures 3 & 4). The tissue remaining on the edge of the eyelid formed the dorsal part of the surgical wound. The removed tissue contained the aberrant cilia. The skin edge remaining below the wound was freshened and sutured to the dorsal part of the wound along the eyelid margin by using 5-0 nylon in a simple interrupted pattern. The suture ends that were directed toward the cornea were cut short to avoid corneal rubbing while the ends directed away from the cornea were left long to allow for ease of identification upon suture removal (Figure 5). The procedure was repeated for the upper eyelid of the left eye and for both eyelids of the right eye. In addition, in the left eye, the exposed subcutaneous tissue at the medial canthus was débrided and closed with 6-0 Vicryl (Ethicon) in a simple continuous pattern, and the skin was closed similarly to the other eyelid incisions.

4. The fibrous tissue and cilia have been removed from the upper left eyelid. The dehisced area near the medial canthus was sutured before the new incision was closed.

Postoperative care was aimed at minimizing pain and self-trauma. The dog was fit with an Elizabethan collar and received 2 mg/kg of carprofen (Rimadyl—Pfizer) and 0.05 mg/kg hydromorphone subcutaneously before recovery from anesthesia. Although it is not our standard procedure to administer prolonged analgesia for most eyelid surgeries, because of this dog's history of intense postoperative pain and the owner's wishes, a five-day course of oral carprofen (2.2 mg/kg) and oral tramadol (3.7 mg/kg every 12 hours) was dispensed.

5. Care was taken to keep the suture ends closest to the eyelids short, and those away from the eye were left long for easier removal.

The patient was discharged from the hospital the same day as the surgery (Figure 6). The client was instructed to cold pack the dog's eyes twice daily for five minutes to minimize swelling and to continue the previously prescribed cephalexin and triple antibiotic ophthalmic ointment (Trioptic P—Pfizer Animal Health). The owner was warned to expect some swelling and, possibly, a mild, permanent ectropion because of the large amount of tissue that had been removed during the two procedures, which had led to eyelid thinning.

6. At discharge from the hospital, the dog's eyelids were no longer rolling inward, and it appeared to be comfortable.

FOLLOW-UP

The dog was rechecked two weeks after surgery. The incisions were well-healed, and there was no swelling or discharge from the eyes or eyelids. Two small, superficial corneal ulcers were present and were thought to be caused by the sutures rubbing on the cornea. The sutures were removed, and no contact occurred between the periocular hairs and the cornea or conjunctiva. Because of the ulcers, the triple antibiotic ointment was administered for one more week.

At the recheck four weeks after surgery, the corneal ulcers had resolved, and the dog was comfortable. A slight rolling out of the lower eyelid margins was present, but the results were cosmetically acceptable to the owner.

DISCUSSION

Entropion correction is a surgical procedure commonly performed in general veterinary practice. Although it is not technically difficult, the results must be cosmetically acceptable and allow normal function. Thus, care must be taken to perform the appropriate procedure for each patient and to correctly execute it.

Entropion correction techniques

The initial surgery done by the dog's regular veterinarian was a modified Hotz-Celsus procedure. With this technique, an elliptical-shaped piece of skin is removed from the upper or lower eyelid, and the remaining skin margins are apposed (Figure 7). To minimize the amount of skin removed, it is important to make the initial skin incision close to the eyelid margin, but it should never enter the margin itself.1-6 In this case, removing the eyelid margin adjacent to the eyelash roots effectively split the eyelid, severely thinning it and exposing the eyelash follicles in some places and obliterating them in others.

7. In the Hotz-Celsus procedure, a crescent-shaped piece of tissue is removed from the affected eyelid. The initial incision is about 2 mm distal to the eyelid margin and the more distal incision is placed so as to obtain the desired outward rolling of the eyelid. The incision edges are carefully apposed and sutured. The incision should be well below the cilia, thus sparing them from damage or removal.

The Hotz-Celsus procedure is the most commonly performed surgical entropion correction and is used in cases in which only a small amount of eyelid inversion exists.1-3 As much skin is removed as is needed to roll the eyelid into a normal position when the skin edges are apposed.4,5 It is important to not remove too much skin; the eyelid should not tip outward at the end of the surgery.

Other surgical techniques for entropion repair can be used in animals with extensive rolling of the eyelid margins or that have complicated forms of entropion, such as that which occurs with macropalpebral fissure syndrome (diamond eye). For example, the Stades technique is used to correct the severe upper eyelid entropion seen in chow chows and Shar-peis.1,6-9 With that technique, a large portion of the upper eyelid skin is removed, and the wound is allowed to heal by second intention, which leads to the formation of granulation tissue that contracts and adds a great deal of upward pull to the eyelid. In simple entropion cases in which there is moderate eyelid inversion that requires a stronger outward pull than is provided by the Hotz-Celsus procedure, the orbicularis oculi muscle can be used to create a small pedicle (Wyman canthoplasty) that is advanced away from the eyelid margin and sutured in place to create a stronger adhesion.

Causes of entropion

Before performing permanent surgical entropion correction, it is important to determine the cause of the entropion. There are two basic types of entropion in dogs: primary and secondary.

Primary, or conformational, entropion is due to a combination of hereditary factors including the shape of the dog's face, the length and shape of the palpebral fissure, and the depth of the orbit.1-6 Patients with this type of entropion often benefit from surgical correction once the head has reached its adult size.

Secondary entropion is either spastic in nature or due to cicatrix formation, atonic eyelids, or the loss of retrobulbar fat, which leads to enophthalmos and the rolling inward of the eyelids. Spastic entropion is caused by chronic blepharospasm, a consequence of ocular pain. Surgery should never be the first option in this type of entropion; everything should be done to resolve the primary cause of the pain (e.g. treating a corneal ulcer).1-6 To protect the cornea while the eye is healing, either temporarily tack the eyelid or place a third eyelid flap or bandaging contact on the cornea. If entropion is still present after the primary cause is resolved, then permanent surgery can be performed. If a permanent surgery is performed initially, it could lead to ectropion once the animal is no longer in pain.

Cicatricial entropion is caused by the contraction of scar tissue in the eyelids due to either an injury or surgery, which causes the eyelids to roll in.1-6 Surgery to remove the scar tissue and reconstruct the eyelid is usually required.

Atonic entropion is a rare form for which a specific cause has not been identified but which results in the loss of palpebral tone.6 Techniques used for correcting conformational entropion are often appropriate in these cases as well.2

Because previous medical records were not available in this case, it was impossible to determine the cause of the entropion. Since primary entropion generally manifests in young animals, it would be unusual to have it in an older animal such as this dog.1-6 This dog likely had spastic entropion and may not have needed surgical correction at all.

Eyelid evaluation and surgical plan

A detailed eyelid evaluation should be conducted and the surgical plan made before anesthetizing the animal for entropion surgery. When the animal is anesthetized, the eyelids relax, and if an eyelid evaluation is performed at this time, improper amounts of tissue could be removed. Careful measurements with a ruler or caliper should be taken and marked on the skin to determine the amount of tissue to be removed and the exact location of the incisions. This planning ahead will reduce the likelihood of iatrogenic ectropion in unaffected areas and the removal of too much tissue in affected ones.4 If in doubt, it is always better to undercorrect rather than overcorrect.

In this case, most of the length of the upper and lower eyelids of both eyes was included in the initial incisions. This approach was quite extensive and may have contributed to the postoperative pain initially experienced by the dog. The aberrant placement of the incisions and sutures undoubtedly led to irritation from rubbing on the surface of the eye, self-trauma, and the subsequent incisional infection.

The excessive granulation and scar tissue formation that occurred in this case is unusual and undesirable after entropion surgery. Its formation was due to the extensive tissue removal and subsequent postoperative inflammation and infection. Although we do not know what suture was used in the initial surgery, a potential cause of excessive scar tissue formation is incision closure with large or inappropriate suture material. These problems can be avoided by using small and closely placed bites, carefully handling tissue, and using small (no larger than 5-0) suture material. Nonabsorbable suture material, such as nylon or silk, is preferred as it causes less tissue reaction. With the Hotz-Celsus procedure, only skin sutures are required. However, with some of the more complex procedures such as Y to V blepharoplasty, subcutaneous small-gauge (5-0 or 6-0) absorbable sutures are necessary.1-6

Self-trauma

Self-trauma is a common postsurgical phenomenon that can lead to suture line dehiscence, infection, and scar tissue formation, and it may have contributed to the postoperative morbidity in this case. Avoiding this problem by decreasing irritation to the periocular area during surgery is important. Minimal delicate shaving of the periocular hair and a gentle scrubbing of this area are paramount for preventing irritation. Protecting the surgical site by fitting the patient with an Elizabethan collar or goggles before it recovers from anesthesia will help ensure that it does not traumatize the area while the anesthesia is wearing off. The collar should be kept on the dog at all times until the sutures are removed at about two weeks after surgery.

Client communication

One interesting aspect of this case was the client communication issues that occurred. The client was concerned from the first presentation to her regular veterinarian that her dog was in severe pain and that the incisions were not healing properly. She did not feel that her concerns were being properly addressed.

Perhaps when the surgery did not yield optimal results, the client should have been better informed and the dog referred to a veterinary ophthalmologist to evaluate the situation and make recommendations. Not only is full disclosure of medical errors the ethically correct course of action, it has been shown to result in the most favorable outcomes.10-12

CONCLUSION

This case serves as a reminder that even the most common procedures can have complications. The likelihood of complications can be minimized with careful patient evaluation, selection of the correct surgical technique, meticulous surgery, and proper postoperative management. When mistakes do occur, the client-veterinarian relationship may be salvaged with honesty and open communication.

This case report was provided by Juliet R. Gionfriddo, DVM, MS, DACVO, and Julie Yeager, DVM, Department of Clinical Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523.

REFERENCES

1. Severin GA. Severin's veterinary ophthalmology notes. 3rd ed. Fort Collins, Colo: Severin Press, 1995;188-196.

2. Crispin SM. Notes on veterinary ophthalmology. Ames, Iowa: Wiley-Blackwell, 2005;81-86.

3. Moore CP, Constantinescu GM. Surgery of the adnexa. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 1997;27(5):1011-1066.

4. Bedford PG. Diseases and surgery of the canine eyelids. In: Gelatt KN, ed. Veterinary ophthalmology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1999;535-582.

5. Miller WW, Albert RA. Canine entropion. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet 1988;10:431-436.

6. Van der Woerdt A. Adnexal surgery in dogs and cats. Vet Ophthalmol 2004;7(5):284-290.

7. Lackner PA. Techniques for surgical correction of adnexal disease. Clin Tech Small Anim Pract 2001;16(1):40-50.

8. Stades FC. A new method for surgical correction of upper eyelid trichiasis-entropion: operation method. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 1987;23:603-606.

9. Stades FC, Boeve MH. Surgical correction for upper eyelid trichiasis-entropion: results and follow-up in 55 eyes. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 1987;23:607-610.

10. Silverman J, Kurtz SM, Draper J. Skills for communicating with patients. 2nd ed. Oxford, England: Radcliffe Medical Press, 2005;117-140.

11. Shaw JR, Adams CL, Bonnett BN. What can veterinarians learn from studies of physician-patient communication about veterinarian-client-patient communication? J Am Vet Med Assoc 2004;224(5):676-684.

12. Mazor KM, Reed GW, Yood RA. Disclosure of medical errors: what factors influence how patients respond? J Gen Intern Med 2006;21(7):704-710.