Could your veterinary job destroy your life?

A young mother, athlete, and veterinary practice manager suffered through extreme fatigue and muscle pain for three years before she discovered her life would never be the same. Could the same thing happen to you simply because of where you work?

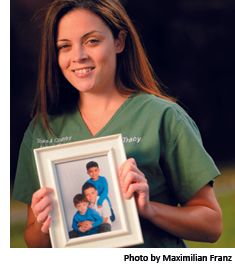

Tracy Vargas is not the mom she used to be. She simply doesn't have the energy. Her joints hurt, she gets frequent headaches, and she finds herself short of breath with the slightest physical activity. Often, it's difficult just to get out of bed.

For Vargas, practice manager at Town and Country Animal Clinic in Olney, Md., life hasn't been the same since she contracted bartonellosis more than three years ago. Her three sons, ages 11, 7, and 5, do their best to put on a brave face and be understanding on the days when Vargas just can't do the things she'd like to do.

“It's heartbreaking as a mom,” Vargas says. “I hate the days that I'm short on patience due to the constant pain and fear that looms over me every day. I sometimes watch them sleep and I cry, praying that the air comes to my lungs and the chest tightness goes away. And then there are those dreaded days when I have to say, ‘Sorry, boys, find something quiet to do because Mommy's having a rough day.' That makes me feel like a failure.”

Until May, Vargas didn't even know what was wrong with her body-and neither did anyone else. After countless visits to her physician, she was diagnosed with everything from fibromyalgia to a pulmonary embolism. It wasn't until talking to Town and Country's practice owner, Dr. Wendy Walker, that she began to wonder if she could find answers through veterinary testing.

Dr. Walker had experienced similar symptoms, so the pair sent blood samples to Dr. Edward Breitschwerdt, DACVIM, who's researching the Bartonella species through his role as professor of medicine and infectious diseases at North Carolina State University College of Veterinary Medicine in Raleigh, N.C. Sure enough, Dr. Breitschwerdt identified the infection in both women's blood. They finally had an answer-though one nobody likes to hear: They had contracted bartonellosis, a debilitating zoonotic disease that stems from the Bartonella bacteria found in many pets' blood and most commonly transmitted to people when cat bites or scratches are contaminated with flea excrement.

“This has destroyed my life on every level,” Vargas says.

From running to rest

Vargas' running shoes sit in her closet, largely unused these days. They used to travel all over her neighborhood miles at a time, rain or shine five days a week. Vargas would stride through the crisp morning air almost effortlessly, reveling in the challenge and pushing herself harder each run. Had she known what her life would become, she might have taken a few extra seconds each day to cherish this exercise and reflect on the amazing effort her body could produce.

Once the muscle pains and headaches kicked in, Vargas' fitness regimen came to an abrupt halt. She became short of breath just walking, let alone trying to shave a few seconds off her mile time. So she shifted her energy into a different venture: managing the disease that has changed her life in a way that so few people understand.

Even her physician was stumped. “A lot of physicians aren't aware of it,” Vargas says. “You say bartonellosis and their faces just scrunch up. That's scary to me. Many people get sick, and their doctors tell them they don't know what's wrong. This is something that the public needs to be aware of.”

To manage the disease, Vargas is seeing an internist who also uses holistic care. Her treatment consists mainly of taking vitamins and supplements to build up her immune system, which was so taxed for three years while she fought the infection. “It's sad to say, but he's the only doctor I've talked to who is not only familiar with zoonotic disease but believed in it and was educated on how to treat it,” Vargas says.

And while some of her symptoms have decreased in intensity, she knows the recovery process won't be speedy. “I don't know if I can ever get back to 100 percent, but I'm determined to get as close as possible,” Vargas says. “If there's anyone who can get there, it's me.”

Mystery cause

Perhaps the most unsettling part of Vargas' ordeal is that she still doesn't know how she became infected. The bacteria could have entered her system through a scratch or bite at the veterinary clinic, or it could have happened at home-Vargas has three cats and two dogs. No single incident sticks out in her mind, but if there's one good thing to come out of the diagnosis, it's that she and her co-workers are now much more aware of the disease.

“I have to admit, I really wasn't educated on bartonellosis,” Vargas says. “I didn't know much about it, and I certainly didn't think of it as a threat.”

The team at Town and Country now focuses more on hand washing and treating scratches they get from pets, and employees use even more caution when handling fractious animals. They also take the opportunity to educate clients on the disease, armed with the knowledge of just how much it has affected their friend and co-worker. “They've watched me suffer for three years-they know what it can do,” Vargas says. “It's kind of hard not to be affected by it.”

Working toward normalcy

Perhaps one day, scientists will find a cure for bartonellosis. For now, Vargas works toward getting back to normal-as normal as her diagnosis allows her to be, anyway. “It's hard to look at yourself in the mirror and say, ‘You're not a bad mom, you just have limits you didn't have before,'” Vargas says.

The running shoes will once again see the light of day, though it may take some time. Vargas can finally walk reasonable distances without losing her breath, and she hopes to begin running again by next summer. She now works four days a week-some from home-and may eventually return to her six-day-a-week schedule as the disease allows. Until then, she'll continue to lean on her understanding family while she progresses with her recovery.

“I'm very lucky-I have a supportive family that is there when I need it,” Vargas says. “I want to be an independent person, but I just can't be.”

Newsletter

From exam room tips to practice management insights, get trusted veterinary news delivered straight to your inbox—subscribe to dvm360.