CSU veterinarians on front lines in the hunt for COVID-19 vaccine

An engineered form of a common bacteria may be the key to creating a vaccine against the novel coronavirus.

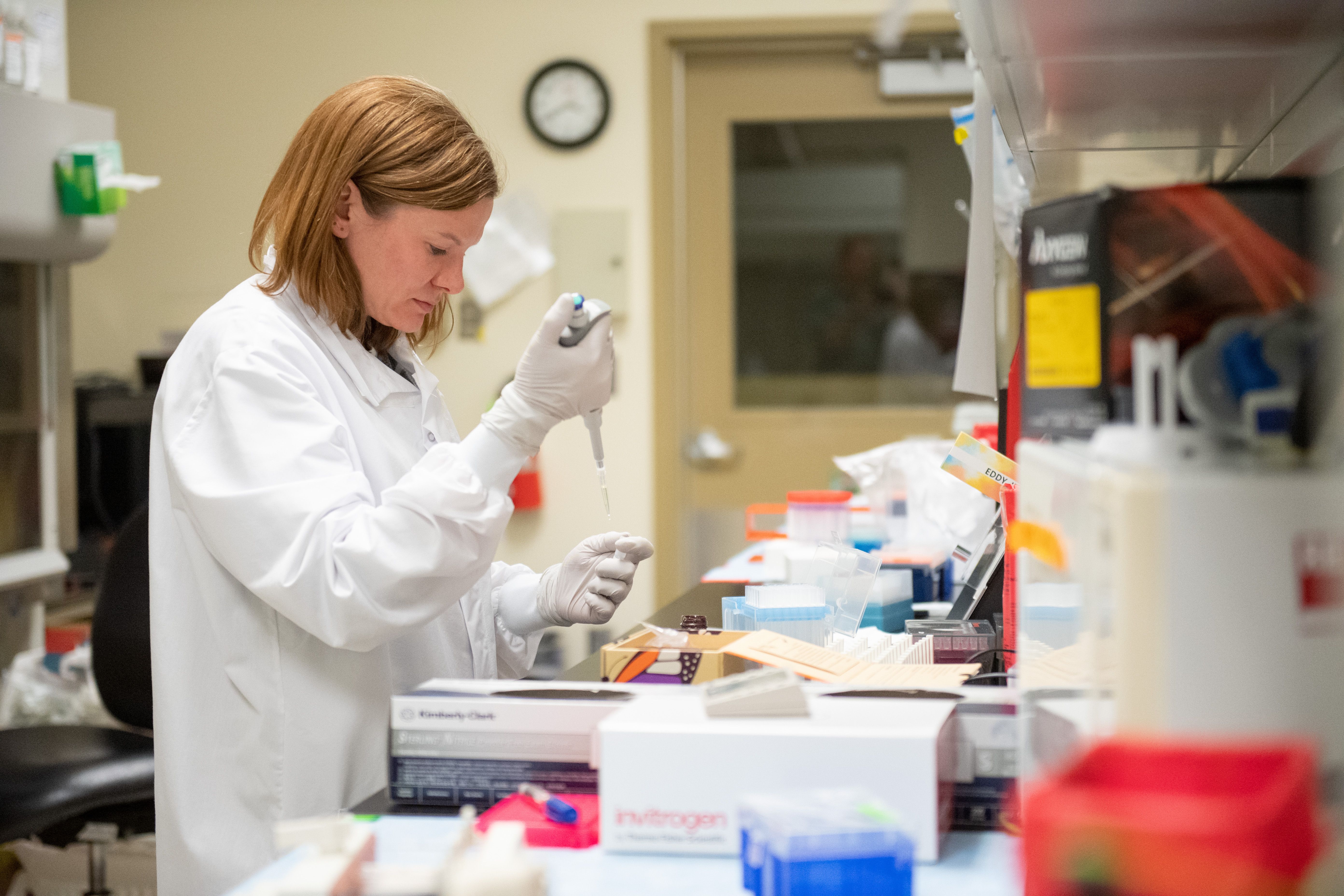

Allison Vilander, DVM, DACVP, working at Colorado State University College of Veterinary Medicine and Biological Sciences to isolate DNA for use in vaccine construction. (Photos by John Eisele)

A fortuitous confluence of vaccine research at Colorado State University in Fort Collins could result in a vaccine for the novel coronavirus responsible for COVID-19. The key: a genetically modified form of Lactobacillus acidophilus that holds promise in preventing the virus from attaching itself to cells in the mucous membrane.

CSU researchers have been studying vaccine platforms for more than a decade, reports Gregg Dean, DVM, PhD, DACVP, professor and head of CSU’s Department of Microbiology, Immunology and Pathology. That work initially began with HIV-related vaccine studies, but was found to be useful for other viruses as well. “One that really stuck out was human rotavirus,” Dr. Dean says. “Globally, [rotavirus] causes a lot of morbidity and mortality and we felt we had a real opportunity to do something meaningful.”

Gregg Dean, DVM, PhD, DACVP

‘An easy pivot’

At the same time, Dr. Dean and his team have been working toward a vaccine for feline coronavirus, with funding from Morris Animal Foundation. “With the emergence of COVID-19, we realized that this vaccine platform could be quickly applied to the human condition, so we began work on that,” Dr. Dean says.

It was an easy pivot, he adds, because the vaccine platform was well understood, and ongoing research had revealed interesting similarities between the human COVID-19 and feline coronavirus. “When we settled on the strategy for the feline virus, we looked at the human virus and the same features were there,” Dr. Dean notes. “So immediately we can identify the sequences that were similar in the human virus and basically substitute them for the sequences we had selected from the feline virus.”

Targeting the spike protein

Dr. Dean’s research team is concentrating on the spike protein that enables the coronavirus to attach itself to host cells. “That spike has a region on it that binds to the host target cell in a very specific way through a host receptor,” Dr. Dean explains. “It’s an amazingly complicated interaction because once the spike binds with the host cell, conformational changes take place. The shape of the spike protein changes, allowing it to bind even tighter to the host cell. But there are a couple of sites that functionally allow that shift in structure to take place, and we felt if we could block those sites and prevent those structural shifts, then we could inhibit that strong binding between the virus and the host cell.”

Two sites in the spike protein have been identified that are considered particularly important, and it is there that the vaccine strategy is focused. In addition, another protein also in the virus could expand the overall immune response against the virus.

“We felt it was important to be very targeted because there is a condition that can occur called immune enhancement,” Dr. Dean reports. “Sometimes an immune response can actually increase susceptibility to virus infection or make the disease more severe. That’s been the primary problem encountered with feline coronavirus vaccines, so it was something we obviously wanted to avoid in the human vaccine.”

L. acidophilus has been under study as a possible vaccine platform for nearly a decade. It was chosen for the CSU COVID-19 study because it is well understood, and its health benefits include a boost to the immune system.

“It’s important to note that we took the probiotic bacterium that everyone is familiar with and modified it into a drug using gene modification technology,” Dr. Dean says. “We have inserted critical virus sequences into the bacterium so that it interacts with our immune system and induces that immune response against the virus.”

The need for a vaccine to prevent COVID-19 is dire. Close to 100,000 have died from the disease worldwide, and officials with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization warn that coronavirus could become a seasonal health issue like influenza.

However, Dr. Dean reminds us that such work is extremely complicated, time-consuming and not always successful. “In the end, most vaccines fail,” he says. “It’s very difficult to develop a vaccine, especially against challenging pathogens like the coronavirus.”

At CSU, trials for a feline coronavirus vaccine are expected to begin in the fall, and work is proceeding as quickly as possible on a vaccine for COVID-19. “There are a couple of steps that take time and can’t be rushed,” Dr. Dean says. “But we hope to have a construct ready to test in animals in two months. If we see signs of success there, we will assess what the next steps should be.”

The CSU research team includes Allison Vilander, DVM, DACVP, assistant professor in the school’s Department of Microbiology, Immunology and Pathology, and Tony Schountz, PhD, associate professor and expert in zoonotic viruses. Collaborators at the North Carolina State University College of Veterinary Medicine are also contributing to the work.

Veterinarians and vaccine research

According to Dr. Dean, the role of veterinarians in vaccine research is critical. “Emerging pathogens are coming out of animal species and jumping into the human population,” he explains. “In many cases, veterinarians have been studying these diseases in animals for many years, and that is clearly the case with the feline coronavirus. We have gathered a lot of knowledge about [these diseases], and we clearly have a role in addressing the problem when they jump to humans. Many other veterinarians are involved in research. I know many of them are working very hard to direct their efforts at the current pandemic.”

At the community level, clients are increasingly asking their veterinarians about the risk of catching the coronavirus from their pets, and vice versa. News of a tiger at the Bronx Zoo in New York testing positive for COVID-19 has brought the issue to even greater prominence. It is believed that the big cats at the zoo contracted the virus from a caretaker who also tested positive.

“A picture is beginning to emerge that cats are, indeed, infectible by COVID-19, and that cats can shed the virus,” Dr. Dean says. “But what we don’t know is whether cats can infect other cats or can infect people. There are high-quality studies going on that should give us those answers.”

Don Vaughan is a freelance writer based in Raleigh, North Carolina. His work has appeared in Military Officer, Boys Life, Writers Digest, Mad and other publications.