Cutting-edge stem cell cures

UC Davis Veterinary Institute of Regenerative Cures is working to develop new therapies for both humans and animals.

Dr. Amir Kol (left), a postdoctoral student, and Naomi Walker, a research associate, work in the lab at the Veterinary Institute for Regenerative Cures at UC Davis. Photos courtesy of UC Davis.The Veterinary Institute for Regenerative Cures (VIRC), housed at the veterinary school of the University of California, Davis, is working at the leading edge of stem cell research and therapy by developing and then integrating regenerative medical discoveries into clinical practice.

Founded in 2015, after more than seven years of program building and basic research, the VIRC has developed teams of basic researchers, clinicians, students and technical staff to translate discoveries into treating specific disease targets. The program focuses primarily on developing and conducting relevant clinical trials in naturally occurring diseases of animals and translating those research findings into clinical practice.

Dr. Dori Borjesson“We now have the infrastructure and a collaborative, scientific, like-minded group of people to begin the work,” says Dori Borjesson, DVM, MPVM, PhD, DACVP, director of the institute and professor and chair of pathology, microbiology and immunology.

VIRC has partners in the UC Davis School of Medicine and the departments of Biomedical Engineering and Animal Sciences. It also has teams that develop large animal models of disease for preclinical human trials. Those faculty work closely with counterparts in the School of Medicine Institute of Regenerative Cures at UC Davis.

A truly integrative approach

“We convert all that we learn in the lab into the clinical practice,” Borjesson says. “We look at how the stem cells work in the lab, and then how the cells work with cells within the body-the immune system-and how the cells work in the context of inflammation and different types of clinical lesions. We then try to identify diseases that have similar immune cell and inflammation profiles that we hope will respond to stem cell treatment.

“We're most successful when we integrate our work with functional and engaged clinical teams to explore stem cell therapy further in the clinical setting to help cure diseases,” she explains.

VIRC has both small and large animal disease teams working on myriad diseases. For example:

- The neurologic disease team is working on spinal cord injury and spina bifida in dogs and equine neurologic disease. One member of the team is a clinician and is board-certified in equine medicine and neurology; another is a professor of surgery and radiology.

- The ophthalmology team is working on keratoconjunctivitis sicca (dry eye) in dogs and recurrent uveitis in horses.

- The inflammatory disease team works on feline oral inflammation (i.e., cats with chronic gingivostomatitis), and a group is studying the use of stem cells for inflammatory bowel disease in dogs. One member of this team is a staff veterinarian from the Pathology, Microbiology and Immunology Department.

- The orthopedic group works with stem cells as potential treatment for problems with tendons, ligaments, joint lesions, and lesions of the feet and hooves of horses.

- The dentistry and oral surgery team looks at jawbone regeneration by using a tissue engineering approach (scaffolding combined with a bone growth promoter called bone morphogenetic protein). This collaborative team includes tissue engineers from the Biomedical Engineering Department.

The researchers at VIRC are working toward developing biomarkers-critical to determining how stem cells work-to help inform clinical trials, rather than using stem cells to treat every disease. “We're trying to figure out if we can predict which animals may respond to therapy and how the stem cells are working,” says Borjesson. “That's a major area of interest, both for horses regarding lesions of the hoof, as well as oral lesions in cats. As we try to treat them, we're attempting to figure out what the stem cells are doing so we can best focus on those diseases that might respond.”

In conjunction with the research and clinical programs, VIRC is developing standard protocols for quality assurance and quality control. “There are a lot of different products in the marketplace, variably characterized,” Borjesson explains. “We're trying to move forward on how best to apply stem cell therapy, working toward personalized medicine, getting a relatively standard product out there. We'll be working with the FDA on trying to conform to its new guidelines on cell-based products for animal use.”

In addition to research, VIRC focuses on establishing an educational program. “We have a group interested in developing curricula and educating undergraduates, veterinarians and others via continuing education on regenerative medicine and its impact in veterinary medicine, so that's another one of our goals. We want to educate future leaders in veterinary regenerative medicine,” says Borjesson.

Stem cell therapy of specific disease of cats, dogs and horses

VIRC's other focus is to treat animals with naturally occurring diseases. “We look at the disease, how we can best characterize it, treat animals under clinical protocols, and then monitor their response to therapy,” Borjesson states. “We try to develop stem cell protocols to help animals with a variety of diseases, but we also try to focus on diseases and protocols that can inform human clinical trials in inflammatory disease, spinal cord injury, ocular disease and so on. We're trying to leverage what we learn in the lab and clinic in animals to help similar human diseases. This has worked really well for us.”

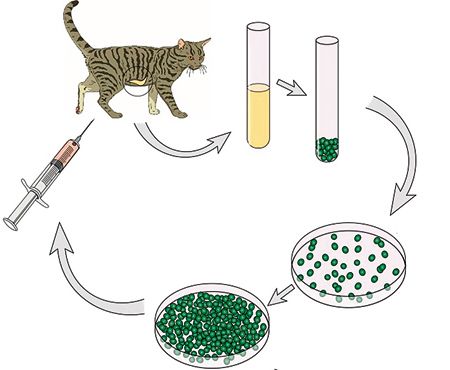

Feline disease. The disease for which VIRC has received most attention is feline chronic gingivostomatitis, which affects about 1 percent of cats seen in clinical practice. It's a painful, severe, chronic inflammatory lesion of a cat's gingiva and the moist tissue that lines its oral cavity.

Cats with the disease chronically salivate, don't eat properly due to the pain of the oral inflammation, and lose weight. There's no ideal treatment for this disease. The current protocol is to extract all teeth. If the cat doesn't respond to this therapy, it often will have to undergo lifelong therapy with corticosteroids and antibiotics.

“Stem cells have been effective in treating this disease, with results that vary from clinical cure to substantial improvement in about 70 percent of these patients,” Borjesson notes. “We treat these cats with two doses of intravenous stem cells. We've noticed that the stem cell therapy is a very potent anti-inflammatory, so we get resolution of the oral inflammation. Along with that we see concomitant changes in the inflammatory biomarkers in the blood.

“We're working to optimize that stem cell protocol,” Borjesson continues. “We think the stem cells are modulating the immune response, altering T-cell activation.”

The work in Borjesson's lab focuses on how stem cells interact with T lymphocytes and how they alter T-cell function and phenotype. “Our work with cats suffering from gingivostomatitis has been an excellent model of how stem cells work and is a success story regarding stem cell therapy. We can also sample blood and oral tissues to learn about how stem cells function in a living animal.”

An illustration of the procedure used to isolate fat-derived stem cells from cats to treat chronic oral inflammation.

Borjesson's lab receives funding from the National Institutes of Health to continue work on cats as a model of human oral diseases (e.g., oral lichen planus, stomatitis, pemphigus) that are similar to the feline disease. They are working with Nasim Fazel, MD, associate professor of dermatology at the UC Davis School of Medicine. Fazel is a board-certified dermatologist and dentist who routinely treats human patients with these chronic oral inflammatory diseases.

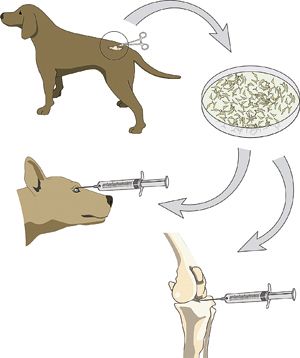

An illustration of the procedure used to isolate fat-derived stem cells from dogs to treat dry eye and orthopedic lesions.Canine disease. Currently underway are clinical investigations of the use of stem cells in inflammatory bowel disease, spinal cord injury and keratoconjunctivitis sicca in dogs.

VIRC is recruiting dogs with spinal cord injury that have no deep pain perception. As part of the study, the dogs will undergo surgery and concurrent stem cell therapy, imbedded in a gel matrix, at the site of lesion. The objective is to improve the outcome for these patients with severe disease. Assessment will include gait analysis over time and physiologic parameters, as well as complete neurologic examinations to determine safety and efficacy of the stem cell therapy to treat spinal cord injury in dogs.

“Our goal is to enroll dogs for stem cell therapy that have a fairly poor prognosis with surgery alone, with the hope that stem cells, and their ability to assist in neural repair, will promote recovery,” says Borjesson.

Equine disease. For equine patients with neurologic disease, the VIRC team will inject stem cells intrathecally, or into the spinal canal. “We're going to track the cells, as we also have a stem cell imaging team that labels stem cells and sees where they go,” Borjesson says. “We'll start, as we normally do, with a safety study in normal horses.”

After that, the team will look at using stem cells for the chronic inflammatory sequela of equine protozoal myeloencephalitis, as well as for wobbler syndrome (cervical vertebral instability, cervical spondylomyelopathy, and cervical vertebral malformation).

The idea behind the use of therapy for these diseases is that stem cells have a basic neuroregenerative and neuroprotective function. “Once we're assured of safety, we'll enroll a few animals with either of those equine neurologic diseases,” states Borjesson. “Animals to be enrolled are those individuals that don't have a lot of other options, either because they have severe disease, might be considered unsafe, or may otherwise be euthanized. We'll begin with such individuals, and if we see safety and efficacy, we will then move stem cell therapy to client-owned animals with more moderate neurologic disease.”

Ed Kane, PhD, is a researcher and consultant in animal nutrition. He is an author and editor on nutrition, physiology and veterinary medicine with a background in horses, pets and livestock. Kane is based in Seattle.

Podcast CE: A Surgeon’s Perspective on Current Trends for the Management of Osteoarthritis, Part 1

May 17th 2024David L. Dycus, DVM, MS, CCRP, DACVS joins Adam Christman, DVM, MBA, to discuss a proactive approach to the diagnosis of osteoarthritis and the best tools for general practice.

Listen