Dental probes and explorers-musts for examination

A few these tips for these handy dental tools.

Dental probing and exploring should be part of every professional oral hygiene visit. Here are some tips on what instruments to use and what to look for in your canine and feline patients.

Periodontal probe

A periodontal probe is used to measure the depth of the gingival sulcus and periodontal pockets in millimeters to help evaluate the extent of periodontal support. The probe is often referred as the "stethoscope and dipstick" of tooth support.

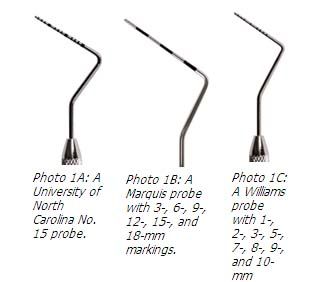

Probes vary in cross-sectional design (rectangular/flat, oval, or round) and in millimeter markings at the calibrated working end. Some probes are marked in 1-mm bands (Photo 1A), while others are marked every 3 mm (Photo 1B). I prefer the thin Williams probe (a round, conical-shaped probe with markings at 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 8, 9, and 10 mm) to help evaluate dog and cats (Photo 1C).

Probing depth

Every professional oral hygiene procedure conducted while a patient is anesthetized should include probing and charting. Probing involves inserting the periodontal probe into the gingival sulcus or periodontal pocket and recording the depth in millimeters. The clinical or probing depth is the distance between the base of the sulcus or pocket and the gingival margin.

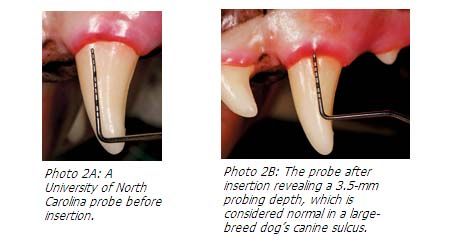

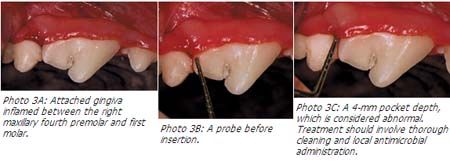

With gentle pressure, the probe will stop where the gingiva is attached to the tooth. Cats normally have probing depths less than 1 mm, while dogs have depths between 2 and 4 mm, depending on the area sampled and dog's size (Photos 2A and 2B). Greater depths indicate loss of attachment, a sign of periodontal disease requiring further evaluation and treatment (Photos 3A-3C).

There are two methods of probing—spot and circumferential. Spot probing involves inserting and withdrawing the probe at a single area per tooth (Photo 4). Because single areas do not represent the entire tooth, an inaccurate assessment may be obtained. Circumferential probing involves inserting the probe in the sulcus or pocket in at least four places (two buccal and two lingual or palatal) around the tooth. This method compensates for inaccurate readings when subgingival calculus or isolated areas of vertical bone loss are present.

Photo 4: An abnormal 7-mm probing depth noted palatally on the left maxillary fourth premolar.

The percentage of support loss, plus clinical and intraoral examination findings, contribute to the creation of a treatment plan. Depending on the client's ability to provide daily plaque control and the patient's willingness to accept such measures, those teeth affected by periodontal pockets composing less than 25 percent of the root height (stage 2 periodontal disease) can be treated with a locally applied antimicrobial or antibiotic. Teeth affected by 25 to 50 percent pocket probing depths (stage 3 periodontal disease) can be treated with extraction or open flap surgery to clean the accessible root surface and, hopefully, save the tooth. Teeth affected by more than 50 percent support loss should be extracted.

Clinical attachment level

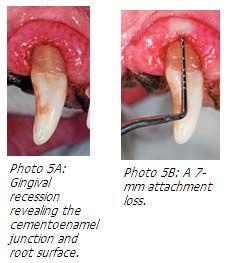

Normally, the gingival margin is less than 1 mm coronal to the cementoenamel junction. With gingival recession, the gingival margin lies apical to the cementoenamel junction. In these cases, the loss of attachment will be greater than the pocket depth.

The clinical attachment level offers greater diagnostic significance compared with the probing depth. Attachment loss, or clinical attachment level, is determined by measuring the distance from the cementoenamel junction to the pocket base. Alternatively, this measurement is determined by adding the probing depth to the gingival recession measurement (distance between the cementoenamel junction to the gingival margin) (Photos 5A and 5B).

Bleeding on probing

While examining the gingiva with the periodontal probe, blood is occasionally observed. Bleeding on probing is not considered normal. Typically a 1- to 2-mm epithelial-lined sulcus exists between the attached gingiva and tooth surface. Disruption of the periodontal support apparatus by disease often results in bleeding on probing and should alert you to look further (Photo 6).

Photo 6: Bleeding on probing.

Dental explorer

A dental explorer has a sharp point or tip used to examine the tooth for surface irregularities, calculus, resorption, necrotic cementum and mobility. The explorer can also be used to look for pulp exposure. Exposure is suspected if the explorer tip sticks into the pulp or porous dentin (Photo 7). The explorer is not used to remove calculus.

Photo 7: An explorer penetrating into the pulp cavity indicating the need for root canal therapy or extraction.

Examples of explorers useful in feline dental pathology assessment include the Orban No. 17 explorer, which has a fine 2-mm tip that extends at a right angle from the shank (Photo 8), and the 11/12 Old Dominion University explorer, which is patterned after the Gracey 11/12 curette. Its thin tip is especially useful for examining areas of tooth resorption. A shepherd's hook explorer, although thicker, can also be used (Photo 9).

Normally you'll encounter a smooth path when inserting and withdrawing the explorer from the sulcus or pocket. When a ledge of subgingival calculus is present, the explorer moves over the tooth surface, encounters the ledge, moves laterally over it and returns to the tooth surface. If fine deposits of subgingival calculus are present, there will be a gritty sensation as the explorer passes over the fine calculus. In cases of tooth resorption and other structural defects, the probe enters the area of dental hard tissue loss (Photos 10 and 11).

Photo 10: Exploring a catâs cementoenamel root resorption.

Photo 11: Exploring furcation involvement in a cat with stage 2 periodontal disease.

SUGGESTED READING

- Baxter CJK. Oral and dental diagnostics. In: Tutt C, Deeprose J, Crossley DA, eds. BSAVA manual of canine and feline dentistry. 3rd ed. Gloucester, U.K.: BSAVA, 2007; 22-40.

- Harvey CE, Emily PP. Oral examination and diagnostic techniques. In: Small animal dentistry. St. Louis, Mo: Mosby, 1993; 19-41.

- Holmstrom SE, Frost Fitch P, Eisner ER. Dental records. In: Veterinary dental techniques for the small animal practitioner. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders, 2004; 1-38.

- Lobprise HB. Treatment planning based on examination results. Clin Tech Small Anim Pract 2000; 15 (4): 211-220.

Dr. Bellows owns ALL PETS DENTAL in Weston, Fla. He is a diplomate of the American Veterinary Dental College and the American Board of Veterinary Practitioners. He can be reachedat (954) 349-5800; e-mail: dentalvet@aol.com