Diagnote: What's your diagnosis?

During the past two decades, clinical research has improved our abiilty to detect several types of lower urinary tract disease in male and female cats.

During the past two decades, clinical research has improved our ability to detect several types of lower urinary tract disease in male and female cats. The objective of this discussion is to emphasize several key concepts.

Database

A 3-year-old neutered male domestic longhaired cat was referred to the Veterinary Medical Center at the University of Minnesota because of intermittent hematuria, pollakiuria and periuria of one year's duration. These clinical signs were treated empirically with an orally administered broad-spectrum antimicrobial. According to the owner, these clinical signs seemed to wax and wane at intervals that did not coincide with the antimicrobic therapy. The antimicrobial was discontinued one month prior to admission to the Veterinary Medical Center. The cat's diet consisted of a dry adult maintenance diet fed ad libitum.

Physical examination revealed that the cat was in good physical condition. Rectal temperature, femoral pulse rate and rhythm, and respiratory rate were normal.

Palpation of the urinary tract revealed that the bladder wall was thickened and painful. Micturition induced by palpation resulted in voiding of a small quantity of bloody urine.

Analysis of urine collected by cystocentesis revealed that it was moderately concentrated (specific gravity = 1.045) and slightly acidic (pH = 6.5; measured by reagent strip). A few struvite crystals of varying size were observed, and there was a conspicuous absence of pyuria. Aerobic culture of an aliquot of the urine sample was negative after 24 hours of incubation. Results of a complete blood count and a screening serum chemistry profile were normal.

Problem list

Problems identified based on the database include nonbacterial feline lower urinary tract disease characterized by hematuria, pollakiuria, periuria and struvite crystalluria. The pollakiuria indicated that the underlying disease involved at least the lower urinary tract. Observation of moderately concentrated urine (specific gravity of 1.045) provided strong evidence that the cat had adequate renal function.

Initial diagnostic plans

In your opinion, are further diagnostic procedures indicated at this time?

Since the lower urinary tract disease is recurrent, the answer is yes. Our experience is that palpation is an insensitive and unreliable method to detect uroliths.

What about detecting uroliths by radiography? Survey abdominal radiography will reveal radiodense uroliths in approximately one in 10 patients with lower urinary tract disease. Double-contrast cystography will detect uroliths in approximately 25 percent of affected cats. Therefore, in order to rule in (inclusion diagnosis) or rule out (exclusion diagnosis) uroliths, survey and contrast radiographic evaluation of the urinary tract was recommended.

Figure 1: A survey abdominal radiograph of a 3-year-old castrated cat illustrating a radiodense urocystolith (arrow).

Follow-up studies

Survey radiographs of the abdomen revealed one large urocystolith (Figure 1). Retrograde positive contrast urethrocystography revealed a urachal diverticulum at the vertex of the urinary bladder (Figure 2). A broad-spectrum antimicrobial was given orally for seven days to minimize the possibility of a urinary catheter-induced urinary tract infection (UTI).

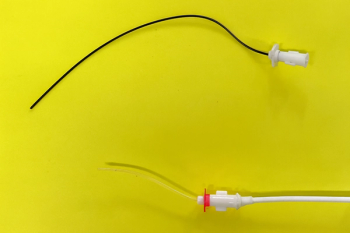

Figure 2: A positive contrast urethrocystogram of the cat described in Figure 1 illustrating a vesicourachal diverticulum.

On the basis of available data, can you predict the mineral composition of the urocystolith? Would you choose ammonium urate, calcium oxalate, calcium phosphate, cystine, magnesium ammonium phosphate, silica or some other type of mineral? What is the basis for your choice?

Our "guesstimate" of the mineral composition of the urocystolith was sterile magnesium ammonium phosphate because:

1. Bacteria were not identified by urine culture.

2. The urocystolith was large, radiodense and had a smooth surface contour.

3. Magnesium ammonium phosphate crystals were observed in the urine sediment.

4. Ammonium urate, calcium oxalate, calcium phosphate and cystine crystals were not observed in the urine sediment.

5. The urolith was located in the urinary bladder (nephroliths are more likely to contain calcium salts).

6. The urine pH was only slightly acidic.

Management

How would you manage this patient? Would you recommend surgical treatment, medical treatment, or a combination of the two?

In a prospective clinical trial of medical dissolution of feline struvite urocystoliths performed at the Minnesota Urolith Center, consumption of a diet designed to dissolve feline sterile struvite uroliths resulted in urolith dissolution in approximately two to four weeks.

Furthermore, in our experience, most feline vesicourachal diverticula are a consequence rather than a cause of lower urinary tract disease. After elimination of predisposing causes (e.g., urocystoliths, infections, urethral obstructions), most vesicourachal diverticula will heal in approximately two to three weeks.

The client was given the option of surgery or medical therapy. Surgical removal of the urocystolith and vesicourachal diverticulum has the advantage of rapid correction of these components of the disease process. However, surgery cannot be relied on to remove subvisual uroliths or to prevent their recurrence. Likewise, surgery is associated with a higher risk of mortality than medical management, although the risk of mortality associated with both types of therapy in this patient are low.

The client requested medical therapy consisting of a diet (Prescription Diet s/d Feline—Hill's Pet Nutrition) designed to dissolve sterile struvite uroliths.

Follow-up evaluation

When should follow-up evaluation be scheduled?

In our opinion, a follow-up evaluation scheduled approximately four weeks after the onset of therapy is satisfactory, unless unexpected developments warrant more frequent evaluation.

Figure 3: A double-contrast cystogram of the cat described in Figure 1 obtained 28 days after initiation of a struvitolytic diet. Note the small urocystolith (arrow) and marked reduction in the size of the vesicourachal diverticulum

At the follow-up, radiodense uroliths were not identified by survey abdominal radiography. Double-contrast cystography revealed a small urocystolith (Figure 3) and marked reduction in the size of the vesicourachal diverticulum (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 4: A positive contrast urethrocystogram of the cat described in Figure 1 obtained 28 days after initiation of therapy. Note the marked reduction in size of the vesicourachal diverticulum (see Figure 2).

The client was advised to continue therapy with the struvitolytic diet and to give an oral broad-spectrum antibiotic known to be excreted in high concentrations in urine for seven days following double-contrast cystography to minimize the possibility of urinary catheter-induced bacterial UTI.

Figure 5: Survey abdominal radiographs of the cat described in Figure 1 obtained seven weeks after initiation of dietary therapy. There are no radiodense uroliths in the urinary tract.

The cat was evaluated three weeks later (seven weeks after the onset of therapy with the struvitolytic diet). During the three-week interval between evaluations, the cat remained asymptomatic. Evaluation of a urine sample collected by cystocentesis revealed no abnormalities (specific gravity = 1.052; pH = 6.0). Survey abdominal radiography and double-contrast cystography revealed no evidence of the urolith or the vesicourachal diverticulum (Figures 5 and 6).

Figure 6: A double-contrast cystogram of the cat described in Figure 5. There is no evidence of urocystoliths or of a vesicourachal diverticulum (see Figure 4).

What is the likelihood that the vesicourachal diverticulum will recur at a later date?

In our experience with more than 50 cases, there have been no recurrences of vesicourachal diverticula in cats.

What is the likelihood of recurrence of struvite urocystoliths?

The general consensus based on clinical experience is that recurrence is unpredictable. Therefore, the client was advised of the availability of diets designed to control several known risk factors associated with formation of struvite uroliths. The need to periodically evaluate the effects of these diets on urine pH and crystal formation was emphasized. Periodic evaluation of the cat by physical examination, urinalysis and survey abdominal radiography during the next 10 months revealed no evidence of lower urinary tract disease.

Key points to recall

1. Several diseases may cause or complicate feline lower urinary tract diseases.

2. Survey abdominal radiographs and/or double-contrast cystography are essential to consistently detect feline uroliths.

3. The mineral composition of uroliths may be predicted on the basis of knowledge of diet history, urine pH and crystalluria.

4. Compliance with consumption of a magnesium-restricted diet formulated to acidify urine typically results in struvite urocystolith dissolution in four weeks.

5. Vesicourachal diverticula often heal spontaneously following eradication of the underlying cause.

6. The efficacy of diets designed to minimize risk factors for recurrent urolithiasis should be evaluated by timely reevaluation of the patient (especially compliance with diet recommendations), periodic examination of fresh urine sediment and determination of urine pH with a pH meter.

7. The efficacy of dietary dissolution of sterile struvite urocystoliths indicates that this therapeutic strategy is a standard of practice.

Dr. Osborne, a diplomate of the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine, is professor of medicine in the Department of Small Animal Clinical Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Minnesota.

Newsletter

From exam room tips to practice management insights, get trusted veterinary news delivered straight to your inbox—subscribe to dvm360.