Drought, floods impact hay crop: Helping horse owners cope

There is an old Italian proverb that says, "Your plate is always full of what you don't want."

There is an old Italian proverb that says, "Your plate is always full of what you don't want."

Precious commodity: Parts of the country still have hay stores, but because of the drought and severe winter, other areas have virtually none.

I am sure that when my grandmother taught that to me she didn't have the weather in mind, but that sentiment certainly can be applied to this year's climatic problems.

Severe droughts are baking some areas of the country, while heavy rains and flooding soak others. In the center of all of this extreme weather are the nation's cattle and horses and the crucial hay crop that is needed to sustain them.

Whether it is too much rain to allow planting, cutting and baling or whether the dry ground and lack of rain doesn't allow any grass growth at all, the result is minimal hay production.

According to the United States Livestock Marketing Center, as of May 1 the nation's hay stores were at the lowest level in 25 years. Obtaining good-quality hay at reasonable prices will be a challenge through the upcoming winter.

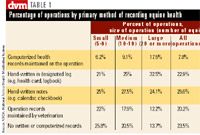

Table 1. Percentage of operations by primary method of recording equine health

The drought gripping many parts of the country holds other threats to livestock as well. Dry, dusty conditions likely will increase the amount and severity of seasonal allergies and create more ocular and respiratory problems for horses.

Hard-packed ground and poor hoof growth may be responsible for more foot problems than usual. Weed invasion and increased toxicity of pasture plants during a drought may lead to other problems, and Vitamin E and selenium-concentration issues could also pose difficulties for horses in some areas.

It is advisable that practicing veterinarians be aware of the challenges faced by horse owners during the drought and be able to provide information, advice and suggestions on how to cope.

Wetting down the track: Dry, dusty conditions are difficult for a horse's respiratory system, present challenges for the serious performance horse and contribute to hoof and joint problems. When water already is in short supply, it often must be used to prepare competition surfaces to hold down dust and to allow horses adequate footing.

An age-old problem

Droughts have been a part of our weather for as long as we have kept weather records, and probably before that. Scientists called paleoclimatologists use historical documents, tree rings, archaeological remains, lake and river sediments and other data to determine what droughts were like over the past 2,000 years.

Connie Woodhouse, a University of Colorado research scientist and Jonathan Overpeck, head of the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Association's (NOAA) Paleoclimatology Program, reported results of their recent research in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society.

They found a greater range of drought severity in the past, as compared to those during more recent recorded history. "Droughts of the 20th century have been only moderately severe and relatively short, compared with droughts of much longer ago," say Woodhouse and Overpeck.

"When we look even further back in time (the 13th and 16th centuries), there is evidence for two major droughts (also called mega-droughts) that probably significantly exceeded the severity, length and spatial extent of 20th-century droughts," they add.

The 20th-century droughts were severe enough. The Dust Bowl of the 1930s was the result of drought conditions compounded by years of poor land management practices that left topsoil depleted. Many farmers were forced from their land and economic devastation was common.

The 1950s drought was caused by a combination of low rainfall and excessively high temperatures. In 1953, 75 percent of Texas recorded below-average rainfall and Dallas temperatures exceeded 100 degrees on 52 days throughout that scorching summer.

The drought of 1987-1989 was the most expensive natural disaster to hit the United States until that time, with losses of energy, water, ecosystems and agriculture estimated at $39 billion.

Scientists can give us some perspective, though, and NOAA's 2003 Paleoclimatology Perspective offers this insight: "Paleoclimatology data suggest that droughts as severe as the 1950s drought have occurred in central North America several times a century over the past 300 to 400 years and thus we should expect (and plan for) similar droughts in the future."

Woodhouse adds, "Even in the absence of poor land management and significant greenhouse warming, future droughts may be much more severe and last much longer than what we have experienced this century."

While everyone should attempt to improve water conservation, land use and other factors leading to a healthier environment, equine veterinarians will be called upon to help deal with the problem at hand – the current drought and hay shortage.

Potential problems, warning

Dust and increased particulate material are common during excessively dry weather. Horses that are somewhat affected by seasonal pasture allergies or other forms of allergic bronchitis are likely to be even more uncomfortable under these conditions. Early recognition, early and aggressive treatment and efforts at management are warranted.

Researchers at the University of Missouri's College of Veterinary Medicine are warning horse owners of the potential dangers of using hay grown in other states. Because of poor hay crops in some areas, horse owners are importing hay from other states and potentially exposing their horses to problems that are not typical with locally grown hay.

"Because of the poor Missouri hay crop," commented Dr. Philip Johnson, a University of Missouri veterinarian, "horse owners imported hay from other states nearby and possibly fed their horses hay that was too high in selenium." Other owners may have purchased poorer quality hay from other sources that was low in Vitamin E as well.

In June, the Georgia Department of Agriculture issued a warning to horse owners concerning problems associated with some shipments of alfalfa hay from Michigan. These shipments contained high percentages of the contaminant weed Hoary Alyssum and 25 horses were reported to have become ill following consumption of this hay.

According to the Agriculture and Food Department of Alberta, Canada, "weeds are exceptionally hardy and can survive and even out-compete desirable species in drought conditions. ... Hungry horses often are more willing to eat poisonous plants if something better is not available and some plants that are normally safe may form toxic compounds when stressed by drought."

Veterinarians should be aware of these concerns and urge clients to inspect new hay purchases, use reputable dealers and utilize local agricultural departments for hay analysis, which usually is surprisingly inexpensive. When hay is in short supply, the trend is to "take what one can get," but equine digestive problems or worse quickly make bargain hay no bargain at all.

Alternative sources

Many horse owners will be looking for alternative hay sources and equine veterinarians should be able to offer some scientifically based suggestions.

Ideally, horses should receive 1.5 percent to 2 percent of their body weight daily in the form of roughage, which is by definition high in fiber (minimum of 18 percent crude fiber). A minimum of 1 percent roughage is required to maintain normal digestive function. Lower fiber sources (11 percent to 15 percent) can serve as alternatives during droughts and will not replace but can reduce the amount of hay that must be fed.

Hay cubes sometimes are used to supplement roughage. These small cubes are made of alfalfa, grass hay or other hay sources and are a nice alternative to hay. Alfalfa cubes can replace alfalfa on an equal-weight basis or replace grass hay on a ratio of a little less than one-pound cubes to two pounds of grass.

Alfalfa pellets can be used to replace most of the forage in the diet but horses need time to adapt to this feed. Beet pulp is a very digestible fiber source and may be used to replace up to half of the normal ration of hay and still provide good digestion. Some areas of the country feed haylage or silage. These can replace some or all of the hay in a horse's diet (haylage) or one half of the ration (silage), but care must be taken in its preparation and storage to avoid spoiled product.

Adjusting to straw

Straw is a surprisingly good hay alternative and can replace all of the needed roughage, provided the diet is properly supplemented with extra protein and minerals, though most nutritionists recommend only partial straw use.

Oat straw is the softest and most palatable choice for horses. Horses need to adjust to consuming straw. They need an adequate water source to prevent impaction colics.

Straw should not be fed to young or old horses that may lack the digestive capacity to utilize this alternative. Some areas of the country may have region-specific alternatives, such as soy hulls or peanut hay and these can provide functional hay supplementation as well.

Be prepared to assist equine clients in dealing with the effects of the current and future droughts and suggest possible hay supplementation for the shortages that most sources predict for the upcoming winter.

Though the prospects seem somewhat bleak at present, scientists assure us that we are merely experiencing a natural cycle and should expect these climatological problems to continue in patterns that we may not yet fully understand.

"With a few adjustments in feeding and management practices", advises Dr. Lori Warren, a researcher at the Colorado State University Department of Agriculture, "horses and pastures can be maintained in good health during a drought" as we wait patiently for our plates to be filled with something else.

Kenneth Marcella is an equine practitioner in Canton, Ga.

Podcast CE: A Surgeon’s Perspective on Current Trends for the Management of Osteoarthritis, Part 1

May 17th 2024David L. Dycus, DVM, MS, CCRP, DACVS joins Adam Christman, DVM, MBA, to discuss a proactive approach to the diagnosis of osteoarthritis and the best tools for general practice.

Listen