Ease the dis-ease of old age in pets

Veterinarians can do better for geriatric dogs and cats and their families. An end-of-life veterinary care expert tells you what breaks her heart and shares practical tips for your practice to help ease the problems clients may face in their pets' last years.

Source: Lap of Love Veterinary Hospice and VetSuccess (Photo: cynoclub/stock.adobe.com)What shocks and saddens Mary Gardner, DVM, co-founder of Lap of Love Veterinary Hospice and In-Home Euthanasia? You might guess it would be something related to euthanasia, since Lap of Love is a network of veterinarians dedicated to end-of-life veterinary care.

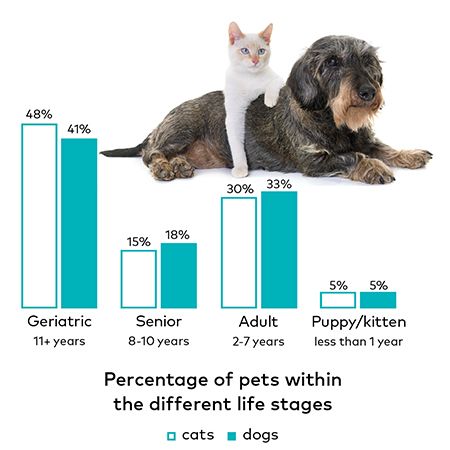

But it's not that. Dr. Gardner says she had noticed that many pets she was scheduled to euthanize had not been to see their veterinarian in quite some time. Her suspicions were borne out when she enlisted the help of data company VetSuccess to conduct a study of 300 clinics of all sizes from around the United States. Their study yielded the statistics you see above. (Their interest piqued by the preliminary data, VetSuccess is now conducting a study of 1,000 clinics.)

“We have to make sure that we don't ever get to the point where we haven't talked to the pet owner in over a year and a half,” says Dr. Gardner. “These pets are really important to us; they're a massive part of our client base.”

Dr. Gardner has been educating the profession about the difference between senior pets and geriatric pets for several years now. “We're seeing a lot more older pets today because we have better medicine and better nutrition and the human-animal bond is different today. We're going to see more geriatric pets,” she says. (Just see below.)

Source: Lap of Love Veterinary Hospice and VetSuccess (Photo: cynoclub/stock.adobe.com)

‘Senior' and ‘geriatric' are not synonymous

Dr. Gardner says that, first of all, veterinary teams need to recognize there's a difference between a senior pet and a geriatric pet. “Geriatricians classify a person as geriatric when they're fragile. I like that word,” she says. “That's what I think of when I have an 11- year-old Lab come in. He can't jump out of the car but has to be lifted.”

Does your practice website help owners of geriatric pets?

“You must have separate senior and geriatric pages on your website,” declares Dr. Mary Gardner. “What do we push in senior marketing? Blood work and x-rays to find an underlying disease. That just sounds like an upsell to me! Nobody has information about older pets on their website, and yet what is the largest pet population in our database? Seniors and geriatrics.”

Lack of education among clients may be one thing that's keeping older pets away from veterinary clinics. Owners simply don't recognize a problem in their geriatric pet and don't know there may be ways to manage a problem. What clients need is education. They need help with, say, “Why does my old cat yowl?” or “Why isn't my old dog sleeping through the night?” When owners Google a problem, “Bam! You want your website coming up, so that they come to you in the morning. Guess what website's coming up? Mine. They can't sleep through the night, and so the next phase is euthanasia,” Dr. Gardner says.

She advises taking the top 10 ailments geriatric pets experience and creating an article or handout about each. She suggests that you make your content species-specific. “No cat lover wants to see something about dogs,” she says. Lap of Love has these handouts available for free download from their website. They're branded to their company, so you may want to create your own instead.

Dr. Gardner said your website should also include information on assessing quality of life and answers to the “How will I know when it's time?” question. She says to include descriptions of the services you offer specifically for senior and geriatric pets, and always include photos. “The owners need to know that you do these services,” she says.

Dave Nicol, BVMS, Cert. Mgmt MRCVS, a colleague of Dr. Gardner's and a frequent lecturer at Fetch dvm360 conferences, recently took her advice to heart. He revamped his practice's website to include client information on senior pets and end-of-life care. For a good example of geriatric pet care content, take a look here.

How often have you said to clients, “Age is not a disease,” when trying to persuade them that their pet may have an underlying treatable disease? But Dr. Gardner says we do need to acknowledge, “Age is a dis-ease-it does bring with it some clinical signs that the patient struggles with.

“And sometimes we're not going to find out what's wrong with them,” she continues. “We're not going to spend money to find out what's wrong with a 15-year-old Lab, but they're still struggling with some urgent issues and not enjoying a good quality of life.”

That's where veterinarians have the opportunity to step in and help the clients who own geriatric pets. She thinks that, in general, veterinarians can do a better job of distinguishing between senior and geriatric pets and helping families deal with the differences. The (somewhat depressing, but realistic) list of physical changes associated with the geriatric stage:

Overall body changes

> Decreased skeletal muscle

> Increased adipose tissue

> Increased drug effects

> Decreased heat production

Nervous system changes

> Decreased brain mass

> Decreased neurotransmitters

> Reduced anesthetic needs

> Decreased autonomic responses

Cardiac and circulatory system changes

> Decreased elasticity

> Decreased sympathetic responsiveness

> Decreased cardiac output

> Decreased compliance

> Reduced bone marrow

> Decreased immune competence

Pulmonary system changes

> Decreased alveolar surface

> Increased stiffness

> Decreased vital capacity/functional residual capacity

> Reduced gas exchange

> Increased work to breathe

Renal and hepatic system changes

> Decreased tissue mass

> Decreased vascularity and perfusion

> Decreased drug clearance

> Reduced tolerance of water and salt loads

These changes are important to be aware of, Dr. Gardner says, especially when a pet is undergoing anesthesia or being given a new drug. (There is much more detail about these physical changes in the 2017 book Treatment and Care of the Geriatric Veterinary Patient by Drs. Mary Gardner and Dani McVety.)

An emphasis on mobility and cognition

Two main areas in which geriatric pets develop problems are mobility and cognition. “Mobility is probably the largest complaint of clients with geriatric pets, and it's the No. 1 issue we have to manage,” says Dr. Gardner. Often the pet can't get up or down, but once they are up they can walk. Older pets may have difficulty walking on tile and wood floors or their legs may splay as they stand in front of their food bowl.

“With these pets we may have osteoarthritis, stenosis and joint problems, but we can't forget about muscle problems. Sarcopenia is the progressive loss of muscle mass. Old dogs and cats just shrivel up,” Dr. Gardner says. “Over time, muscle fibers degrade and are not replaced as well as they used to be.

“I'll have animals that are on the best NSAIDs and pain management, but there's nothing wrong with their joints,” she continues. “They're just weak because their muscles are weak. The fast-twitch fibers in muscles fatigue faster and also degrade faster. Those are the muscle fibers pets use to get up from the floor. Adductor muscles contain more fast-twitch fibers, and so they degrade faster, which is why a pet's legs may splay while sitting in front of a food bowl.”

So, what can be done to help these pets? To prevent sarcopenia, consider increasing protein in the diet. “Taking away protein for kidney failure problems might be hurting our pets because they need that muscle mass,” Dr. Gardner says. Instead, feeding a higher-protein, highly digestible, energy-dense diet to older pets may prevent or slow their decline in body weight and lean body tissue associated with aging.

Also, exercise is important to counteract sarcopenia. “If we can control the pain better, we can get them moving,” says Dr. Gardner. “It's important to keep these pets as pain-free as possible and steadily moving.”

Resources for practitioners and owners of geriatric pets

Dr. Mary Gardner is asked for her recommendations and resources for working with geriatric pets all the time. To answer these requests, she and her company have compiled their recommendations in two handy places:

Lap of Love's website

The company's website has numerous geriatric and end-of-life resources for veterinary teams. Visit lapoflove.com/resources. The password is dvmsupport. Once there, click on the “Geriatrics & Hospice” tab. The site includes articles written by Lap of Love veterinarians, a “Geriatric Questionnaire” for clients to complete (also available here), pain management and anxiolytic protocols for geriatric cats and dogs, and recommendations for products that directly help owners of geriatric pets cope with the pet's difficulties.

Amazon.com

Dr. Gardner also maintains a list of products she frequently recommends (and that are sold on Amazon.com). There you will find her recommendations for mobility support products (like yoga mats), gray-muzzle pet supplies (like “Do Not Ring Doorbell” signs), and books she recommends for veterinarians (like Treatment and Care of the Geriatric Veterinary Patient by Drs. Mary Gardner and Dani McVety) and for owners of geriatric pets (like Dr. Petty's Pain Relief for Dogs by Michael Petty, DVM, CVPP, CAAPM, CCRT).

Don't forget about nonmedical solutions, as well. “We always just throw medicine at a problem, but it's about managing their lifestyle also,” says Dr. Gardner. To help a pet with mobility issues, she recommends products such as yoga or bath mats, booties and toe grips for traction, harnesses to help the pet rise from the floor, and ramps.

For cognition issues in geriatric pets, Dr. Gardner says, “Keep the brain going. One-third of the dog's brain is dedicated to scenting. So, use scenting games for mental stimulation.” Also, this gives owners a way to help their pet. “Owners feel helpless, and they want to do something to help these guys,” she says. She also advises educating clients that a pet with cognitive dysfunction is never to be punished if it has an accident in the house.

Pet owners need veterinarians to help them recognize that a pet is having cognitive problems and there are ways to manage life with these cats and dogs.

Let's try to never be late again

“By the time I see them it's too late,” says Dr. Gardner. “So, I want them seeing you guys before they see us.”

By recognizing the differences between senior and geriatric pets, working to educate owners about the special issues that aging pets develop, offering concrete ideas about ways to manage life with a geriatric pet, providing support for these pet owners who may have a heavy burden, veterinary teams can help reduce that startling statistic about the number of pets that haven't seen a veterinarian in the 18 months before euthanasia. It makes business sense, and it's definitely good medicine to improve the quality of life and ease the dis-ease of old age for geriatric pets and their families.