How to perform a feline perineal urethrostomy

A step-by-step surgical guide, tips to optimize results, and revision techniques, just in case.

Perineal urethrostomy is a surgical method for alleviating urethral obstruction in cats with complicated or recurrent obstructive feline lower urinary tract disease. While long-term quality of life after perineal urethrostomy in cats with obstructive feline lower urinary tract disease is good (as assessed by owners) and the recurrence rate is low, there are several potential intraoperative and postoperative complications. The good news is that with proper technique and equipment, these can be avoided.

Traditional technique for perineal urethrostomy

Step 1. Position the cat in perineal position, with padding under the cranial thighs to prevent neurovascular injury during restraint. Aseptically prepare the perineal area, which usually requires removing the urinary catheter if one was placed before surgery.

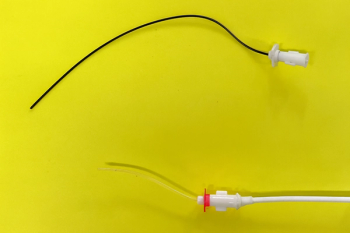

Step 2. After draping, place and secure a urinary catheter. I prefer to use a 5-Fr red rubber catheter, securing it with either a finger trap suture or by clamping the catheter in the penis using Allis tissue forceps. The latter technique allows you to manipulate the penis and provide tension during dissection. It is helpful to use a sterile marker to plan the incision location, tracing a fusiform-shaped incision that includes the penis and scrotum, but terminates at least 1 cm ventral to the anus (Figure 1).

Figure 1 (Figures courtesy of Dr. Christopher Adin)

Step 3. After making an incision with a scalpel blade, incise the subcutaneous tissue until the penis is isolated (Figure 2). Begin dissection around the penis on the lateral side, pulling the penis to the opposite side to create tension on the site of dissection and to improve exposure in that region. I prefer to use tenotomy scissors to perform this dissection because the delicate, blunt tips are well-suited for this area.

Figure 2

Step 4. If you are performing this procedure on your own, after initial dissection it helps to place a self-retaining retractor by using either a Lone Star retractor or several pediatric Gelpi retractors. With proper retraction, the paired ischiourethralis muscles can be palpated, inserting on the ischium on either side of the penis (Figure 3). Isolate these muscles and either elevate them off the bone by using a periosteal elevator or scalpel blade or simply transect them with electrocautery to minimize hemorrhage.

Figure 3

You'll know you've achieved complete transection if you can pass a finger lateral to the penis and into the pelvic canal without resistance. Repeat this on the contralateral side.

Step 5. Next, pull the penis dorsally to apply tension on the penis' ventral ligament, and transect this ligament by using tenotomy scissors Figure 4.

Figure 4

Continue ventral dissection until you can pass a finger without resistance into the pelvic canal in this region as well (Figure 5. Perform final dissection dorsally, but do so with more caution as this is where the urethral blood supply and innervation are located.

Figure 5

Step 6. When the penis is completely mobilized, locate the bulbourethral glands (poorly developed in castrated males). Dissect the retractor penis muscle from the dorsal aspect of the penis, transect it proximally and remove it to expose the urethra on the dorsal surface of the penis.

Step 7. Next, carefully incise the urethra at a distal location with a scalpel blade to make a small stab incision over the red rubber catheter (Figure 6).

Figure 6

The tissue is thicker than you may initially expect, and a firm incision is required to penetrate the urethral lumen, exposing the catheter. Extend the urethral incision by inserting the fine tenotomy scissors into the incision and moving proximally to the level of the bulbourethral glands. The incision may be extended about 1 cm cranial to the bulbourethral glands to maximize urethral diameter, but incision beyond this point will place excessive tension on the stoma when suturing the perineal skin. When a mosquito hemostat can be passed up to the hinge, the urethral diameter is sufficient and suturing can begin (Figure 7).

Figure 7

Step 8. At this point, remove the retractors and place initial sutures beginning at the apex of the urethrostomy (dorsally). I place the sutures from inside to out (urethral mucosa to skin), placing one interrupted suture in the center of the urethra and the proximal aspect of the incision, followed by two more interrupted sutures 45 degrees to the initial suture, spacing about 1 to 2 mm between sutures (Figure 8). It is helpful to preplace all three of these sutures to maximize exposure of the mucosa and achieve perfect placement. Successful apposition of mucosa to skin is crucial at this point, so use of magnification is encouraged. If you are in doubt, take the sutures out and replace them.

Figure 8

Step 9. After placement of these three key sutures at the dorsal aspect of the urethrostomy, complete the stoma by placing interrupted sutures spaced 1 to 2 mm apart, creating a drain board of urethral mucosa. Then lightly ligate the penis and transect it distally before completing the stoma (Figure 9).

Figure 9

Technique modifications

A few modifications have been developed to achieve optimal results.

Tips for surgical success

Use of magnification will ensure correct identification of tissue layers. I recommend 3.5x, wide field.

Use of delicate suture and proper instrumentation will improve the success rate in urethrostomies.

Gentle tissue handling is necessary, as trauma to the mucosa will cause necrosis and dehiscence.

The most common cause of stricture after perineal urethrostomy is failure to adequately dissect the ischiourethralis muscles from the pelvis and failure to correctly appose mucosa-to-skin. Tension-free anastomosis must be achieved.

Place sutures from inside to out.

Stents may be used to encourage healing of partial defects or to prevent urine from contacting the incision during initial healing.

Primary revision of the original stoma is the treatment of choice for failed perineal urethrostomy.

Continuous pattern with absorbable suture. In one study, a minor modification of the technique was described that involves applying two continuous suture patterns with absorbable suture material (polydioxanone).1 This modification allows for decreased operative time, minimizes the volume of suture material in the wound and obviates the need for suture removal, which can often require sedation. No strictures or dehiscences were noted in the 18 cases that were reported, and the overall complication rate was similar to previous reports.

Positioning and approach. Perineal urethrostomy can also be performed with the cat positioned in dorsal recumbency. This is a major advantage in cats with bladder stones, allowing simultaneous cystotomy and perineal urethrostomy without repositioning. To facilitate exposure of the perineum, the pelvic limbs are pulled forward and secured to the table. Although this technique is no more difficult than a perineal approach, it does require a bit of practice before you are comfortable with it.

Postoperative care pointers

- An Elizabethan collar must be placed before recovery from anesthesia, as immediate self-trauma is a common cause of immediate incisional dehiscence.

- Analgesia with a long-acting opioid such as buprenorphine can be combined with a single perioperative dose of a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug in cats that show no evidence of renal dysfunction due to obstructive uropathy.

- Cover the wound with petroleum jelly to minimize urine scald. Removing clots that form on the incision is discouraged as this will cause additional trauma to both the cat and the incision.

- Maintenance of a urinary catheter can be considered to bridge the incisions until a fibrin seal is achieved. Some surgeons avoid using urinary catheters because of concerns that the catheter may cause trauma to the incision line and increase the risk of stricture formation.

- Intravenous antibiotics (cefazolin) are administered at the time of induction but are typically discontinued after surgery unless indicated by specific culture and sensitivity results.

- Recheck urine cultures are indicated every six to 12 months because of an increased risk for ascending urinary tract infections.

Complications

Despite the widespread success of perineal urethrostomy in accomplishing patent urinary diversion in cats, a number of complications have been reported, including stricture of the urethrostomy, subcutaneous urine leakage in the perineal region, hemorrhage, urinary tract infection and incontinence.2 Although some of these complications can be managed conservatively, many require surgical revision to restore urinary function. Thus, almost since the inception of the perineal urethrostomy procedure, there has been a need for revision methods.

Revision techniques

Prepubic urethrostomy. One of the original methods for salvage of failed perineal urethrostomy surgery is prepubic urethrostomy, which involves transecting the urethra and transposing the stoma to a caudal abdominal location, cranial to the pubis. Unfortunately, subsequent experience with this technique showed a high rate of postoperative complications, including urinary incontinence (six of 16 cats) and urine scalding (seven of 16 cats).3 Six cats were euthanized within six months of surgery, and mean survival was only 13 months.

Subpubic urethrostomy. A simple extension of the antepubic urethrostomy technique involves preserving the pelvic urethra and then transposing it to a subpubic position.4 This technique avoids the urine scald associated with prepubic urethrostomy in cats by placing the stoma caudal to the abdominal fat pad. Preservation of more urethral length may also contribute to improved continence with this technique and improved resistance to urinary tract infection, although no large studies have been published to date.

Primary revision. A 2006 study described the results of primary revision of the perineal urethrostomy by revised dissection and mucosa to skin apposition.5 In this study, eight of 11 cats had inadequate dissection to the level of the bulbourethral glands and three had poor apposition of skin to mucosa during initial surgery. Primary revision of the stoma was effective in eight of nine cats available for long-term follow-up.

Transpelvic urethrostomy. Another recent study described transpelvic urethrostomy as an alternative salvage procedure for cats with distal urethral trauma or failed perineal urethrostomy surgery.6 The caudal aspect of the ischium is removed through a ventral approach, and the urethral stoma is translocated to a subpubic position. The advantage of this technique is that it avoids the high rate of incontinence and urine scalding that is seen in prepubic urethrostomy by preserving the intrapelvic urethra and urethral sphincter. Only one cat developed temporary incontinence, which resolved by four weeks after surgery.

Conservative therapy. As many clinicians have learned, conservative therapy with urethral catheterization or urinary diversion can provide an acceptable long-term solution in selected animals with urethral tears and urine leakage. A recent clinical retrospective study evaluated prognostic factors for animals with urethral trauma in 20 dogs and 29 cats.7 Urethral rupture was more common in males of both species, with etiology being most commonly related to vehicular trauma in dogs and iatrogenic injury during catheterization in cats. The presence of multiple traumatic injuries served as the only negative prognostic indicator in this series, with location of rupture, clinicopathologic findings, treatment method (surgery versus catheterization) and etiology having no significant effect on outcome.

Tube cystostomy. Tube cystostomy is an accepted method for short- or long-term urinary diversion. A landmark study performed in an experimental model of intrapelvic urethral transection and primary repair in normal dogs showed that there was no difference in healing of urethral wounds when tube cystostomy was compared to transurethral catheters or both techniques combined.8

A recent follow-up study on tube cystostomy in 76 animals showed that complications were common (49%), although most were treatable through nonsurgical intervention.9 Urinary tract infection was nearly universal (16 of 17 animals that had urine culture checked after tube implantation had positive) results. Inadvertent tube removal was the most common major complication (occurred in 12 of the 76 animals) but was typically handled conservatively (n=8) or by tube replacement (n=4). Only one animal required surgical revision due to uroperitoneum after tube removal. The most common minor complication was irritation around the tube site (n=7) or urine leakage around the tube (n=7). Complication rate was not associated with species, tube type or duration of tube retention.

References

1. Agrodnia MD, Hauptman JG, Stanley BJ, et al. A simple continuous pattern using absorbable suture for perineal urethrostomy in the cat: 18 cases (2000-2002). J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2004;40(6):479-483.

2. McLoughlin MA. Complications of lower urinary tract surgery in small animals. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2011;41(5):889-913.

3. Baines SJ, Rennie S, White RS. Prepubic urethrostomy: A long-term study in 16 cats. Vet Surg 2001;30(2):107-113.

4. Ellison GW, Lewis DD, Boren FC. Subpubic urethrostomy to salvage a failed perineal urethrostomy in a cat. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet 1989;11:946-951.

5. Phillips H, Holt DE. Surgical revision of the urethral stoma following perineal urethrostomy in 11 cats: (1998-2004). J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2006;42(3):218-222.

6. Bernarde A, Viguier E. Transpelvic urethrostomy in 11 cats using an ischial ostectomy. Vet Surg 2004;33(3):246-252.

7. Anderson RB, Aronson LR, Drobatz KJ, et al. Prognostic factors for successful outcome following urethral rupture in dogs and cats. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2006;42(2):136-146.

8. Cooley AJ, Waldron DR, Smith MM, et al. The effects of indwelling transurethral catheterization and tube cystostomy on urethral anastomoses in dogs. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 1999;35(4):341-347.

9. Beck AL, Grierson JM, Ogden DM, et al. Outcome of and complications associated with tube cystostomy in dogs and cats: 76 cases (1995-2006). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2007;230(8):1184-1189.

Christopher Adin, DVM, DACVS

Department of Clinical Sciences

College of Veterinary Medicine

North Carolina State University

Raleigh, North Carolina

Newsletter

From exam room tips to practice management insights, get trusted veterinary news delivered straight to your inbox—subscribe to dvm360.