Idiopathic cystitis (Proceedings)

The most common cause of feline lower urinary tract disease is idiopathic cystitis. Feline idiopathic cystitis, formerly called idiopathic feline lower urinary tract disease, is defined as a disease of undetermined etiology characterized by hematuria, dysuria, pollakiuria and possible urethral plug formation.

The most common cause of feline lower urinary tract disease is idiopathic cystitis. Feline idiopathic cystitis, formerly called idiopathic feline lower urinary tract disease, is defined as a disease of undetermined etiology characterized by hematuria, dysuria, pollakiuria and possible urethral plug formation. This condition overlaps with 2 clinical syndromes of dysuria/pollakiuria syndrome and urinary obstruction. The syndrome of dysuria/pollakiuria in cats is often associated with hematuria and was initially referred to as the "feline urologic syndrome" or "FUS". Idiopathic cystitis is one of several differential diagnoses for dysuria/pollakiuria in cats. Unfortunately many veterinarians assume all cats with dysuria/pollakiuria or urinary obstruction should all receive the same stereotyped treatment without first obtaining a diagnosis. This leads to frustration when cases don't resolve with treatment.

Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses for lower urinary tract diseases in young adult cats from most common to least common include idiopathic cystitis (with or without urethral plug formation), urolithiasis, iatrogenic disorders (urethral tears, urethral stricture), bacterial UTI, neoplasia (lymphoma, transitional cell carcinoma), fungal UTI, prostate disease, and idiopathic detrusor instability. The role of urachal diverticula in lower urinary tract disease in cats is controversial. While cats with diverticula may have persistent clinical signs that have been suggested to be caused by the diverticula, diverticula may spontaneously regress with resolution of lower urinary tract disease suggesting the diverticula are a result of the disease rather than a cause of the disease.6 The causes of lower urinary tract disease in geriatric cats are different than young adult cats. In one study of geriatric cats, the causes from most common to least common were UTI (46%), urolithiasis with UTI (17%), urolithiasis without UTI (10%), urethral plugs (7%), traumatic injury (7%), idiopathic cystitis (5%), and neoplasia (3%). The higher incidence of UTI in geriatric cats versus only 1-2% incidence of UTI in young adult cats with lower urinary tract disease is due to underlying diseases that predispose geriatric cats to UTI such as chronic kidney disease, diabetes mellitus, and hyperthyroidism.

Diagnosis of idiopathic cystitis is based on ruling out other known causes of lower urinary tract disease; it is an exclusion diagnosis. The minimum work-up should consist of a urinalysis, urine culture, and abdominal radiographs, although these do not rule-out all possible causes of lower urinary tract disease. Cases that persist beyond 5 to 7 days may require additional work-up, such as ultrasound or contrast radiographs to rule out radiolucent uroliths and neoplasia, and urine cultures for unusual organisms (mycoplasma and ureaplasma). Cystoscopy may be used to confirm the diagnosis of idiopathic cystitis.

Idiopathic cystitis

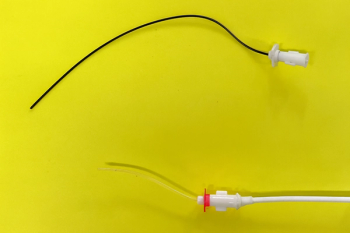

There are two clinical forms of idiopathic cystitis: nonobstructive and obstructive. In the nonobstructive form, male or female cats present with a history of hematuria, dysuria, and pollakiuria. There tend to be episodic clinical signs with acute onset. Understanding the natural course of the disease is critical to accurately interpret any proposed treatment effects. Idiopathic cystitis usually resolves spontaneously within 5 to 7 days regardless of treatment, thus any therapy may appear effective. Recurrence is common but unpredictable; cats can be normal for days to years between episodes. The obstructive form occurs in male cats due to occlusion of the urethra by urethral "plugs". Urethral plugs are not uroliths, rather uroliths are a differential diagnosis for cause of urethral obstruction. Urethral plugs differ from uroliths in that they lack organized internal structure. They are semi-solid plugs composed of matrix and crystals (usually struvite) and often have the consistency of thick toothpaste. The matrix consists of varying quantities of proteins and cellular debris (RBC, WBC, epithelial cells). If obstruction is due to true uroliths, the cause is urolithiasis, not idiopathic cystitis. Massive crystalluria can lead to the formation of multiple small uroliths, which are like "sand" and can cause obstruction. This illustrates a continuum between urethral plugs and urolithiasis. Urethral obstruction may occur abruptly without prior clinical signs or may be preceded by dysuria/pollakiuria. Urethral matrix plugs may begin to form in female cats and non-obstructed male cats, but they pass out the urethra without becoming lodged. Increased crystalline component of urethral plugs may solidify the plug causing obstruction. Urethral obstruction is life-threatening. Urethral obstruction tends to recur with subsequent episodes of idiopathic cystitis.

The etiology of idiopathic cystitis is unknown, but there are three main hypotheses on its origin. Viral infection of the lower urinary tract has been hypothesized to cause idiopathic cystitis. Experimental studies have suggested that infection of the feline lower urinary tract with a cell-associated herpesvirus (CAHV) may induce hematuria in young SPF cats. CAHV can persist in lower urinary tract tissues for prolonged periods of time; however, CAHV does not reliably produce the typical clinical disease. It does, however, resemble herpesvirus infections in other species (genital herpes infections in man) and represents an attractive hypothesis for pathogenesis. Viral particles have been identified in many spontaneous urethral plugs but they may represent causative agents or they may simply reflect urinary excretion from viremia.

Excess dietary intake of minerals (magnesium) resulting in struvite crystalluria has been hypothesized to cause idiopathic cystitis. The crystals hypothetically irritate the bladder mucosa resulting in inflammation. Support for this theory is even weaker than the viral hypothesis. Data supporting this hypothesis is based primarily on experimental models of feline struvite urolithiasis and does not support crystalluria as a cause of idiopathic cystitis. Crystalluria probably does play a role in the genesis of urethral obstruction due to urethral plugs. The crystals act to solidify the plug resulting in obstruction. While most urethral plugs contain struvite crystals entrapped within the matrix plug; some urethral plugs may contain calcium oxalate or urate crystals or and some plugs lack any crystalline component. Indirect evidence suggests that dietary therapy designed to prevent struvite crystalluria reduces the incidence of recurrent urinary obstruction.

Drs. Buffington, Chew and Westropp have suggested that idiopathic cystitis is feline interstitial cystitis, similar to human interstitial cystitis which occurs mainly in women. The etiology of human interstitial cystitis is also unknown. Cats with idiopathic cystitis have decreased size and function of their adrenal glands. The specific cause and effect link between the adrenal abnormalities and FIC in these cats is not known, but this may provide insight into the pathogenesis of this disorder. This also correlates to observations that cats with idiopathic cystitis tend the have recurrences during periods of environmental "stress". Cats with idiopathic cystitis have increased catecholamine levels and increased bladder permeability during periods of stress.

Treatment of Idiopathic Cystitis

There is no proven effective therapy for treatment of idiopathic cystitis. The disease usually resolves spontaneously within 5-7 days in non-obstructed cats. Antibiotics are only indicated for documented UTI or prophylaxis following indwelling urethral catheterization. Management of urinary obstruction is similar to urinary obstruction of other causes. Although several treatments have been suggested for idiopathic cystitis, none have been proven more effective than placebo. Antibiotics are not effective in treatment of idiopathic cystitis. Methylene blue (a urinary antiseptic) and phenazopyridine (a urinary analgesic) are contraindicated in cats because they cause Heinz body hemolytic anemia and methemoglobinemia. Corticosteroids have been suggested to reduce inflammation in idiopathic cystitis, but a double-blind clinical trial showed no improvement with steroids compared to placebo. Prednisone also did not reduce inflammation in an experimental model of idiopathic cystitis and predisposed the cats to UTI and pyelonephritis. Steroids increase catabolism, which can worsen postrenal uremia from obstruction. Intravesical DMSO also was not beneficial, and it may predispose the cat to UTI and pyelonephritis. Intravesical PGE1 was also not effective in an experimental model of interstitial cystitis. Propantheline is an antispasmodic that may reduce the severity and frequency of "urge" incontinence in cats with non-obstructed idiopathic cystitis. However, this is symptomatic only and does not affect the rate of recovery. Although there is no research data to support narcotics, some clinicians recommend narcotic analgesia to reduce clinical signs during acute episodes of idiopathic cystitis. Oral butorphanol (0.5-1 mg/kg PO q6-8h) or sublingual (buccal) buprenorphine (0.01-0.03 mg/kg q 6-8 h) may be used to alleviate pain.

Prevention of Idiopathic Cystitis

There is also no proven preventative therapy for idiopathic cystitis. Uncontrolled clinical trials suggest that dietary therapy designed to prevent crystalluria, such as a canned dietary therapy, may reduce the incidence of recurrent FIC episodes and urethral obstruction. Other medical therapies have been recommended to reduce struvite crystalluria in cats with idiopathic cystitis which have not been proven effective including distilled water for drinking water, salt supplementation, semi-moist cat foods or adding water to the diet, etc. Of these measures, adding water to the diet and/or feeding canned diets is the main treatment that appears to reduce recurrence of idiopathic cystitis.

A non-controlled open label clinical trial suggested that amitriptyline (5-10 mg per cat q24h) may be effective for prevention of recurrence of idiopathic cystitis; however clinical response is often minimal.26 Perineal urethrostomy (PU) has been advocated for prevention of recurrent urethral obstruction. Perineal urethrostomy may reduce the incidence of obstruction; however, it does not address the underlying disease process. Perineal urethrostomy can also predispose to ascending UTI, which can lead to infection-induced struvite urolithiasis, along with potential complications including urethral stricture. Although GAG replacement therapy (e.g., glucosamine, pentosan polysulfate) has been recommended for treatment of idiopathic cystitis, one study did not demonstrate any benefit of glucosamine over placebo-treated cats. In this study, most cats were fed more canned food during the study and both glucosamine-treated and placebo-treated cats improved to a similar degree. In a multicenter clinical trial of GAG therapy, pentosan polysulfate (Elmiron) had a small beneficial effect on cystoscopic scores in cats with idiopathic cystitis, but there was no difference in clinical signs compared to placebo. In this study and others, there was a large placebo effect that prevented any measurable benefit on clinical signs. Similarly, a placebo-controlled study of pheromone therapy also failed to demonstrate any benefit. A recent uncontrolled observational study suggested that environmental enrichment along with other behavioral modifications (termed multimodal environmental modification) resulted in significant improvement of the clinical signs of feline lower urinary tract disease and warrants further study. Environmental enrichment normalized many of the catecholamine levels and increased bladder permeability in cats with idiopathic cystitis.

Accurate client education is paramount in the management of idiopathic cystitis because of frequent recurrence and the potential life-threatening nature of urethral obstruction in male cats. Unfortunately, some client information pamphlets and many web pages about "FUS" are misleading or useless. Therefore, effective communication about the nature of idiopathic cystitis and our current understanding of treatment options are important factors that determine client adherence to recommendations.

References

Buffington CA, Chew DJ, Woodworth BE. Feline interstitial cystitis. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1999;215:682-687.

Kruger JM, Osborne CA, Goyal SM, et al. Clinical evaluation of cats with lower urinary tract disease. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1991;199:211-216.

Osborne CA, Kruger JM, Lulich JP, et al. Feline urologic syndrome, feline lower urinary tract disease, feline interstitial cystitis: what's in a name? J Am Vet Med Assoc 1999;214:1470-1480.

Westropp JL, Buffington CAT, Chew D. Feline lower urinary tract diseases, in Textbook of veterinary internal medicine: diseases of the dog and cat, ed. Ettinger SJ and Feldman EC, Elsevier Saunders, St. Louis, 2005, 1828-1850

Buffington CA, Chew DJ, Kendall MS, et al. Clinical evaluation of cats with nonobstructive urinary tract diseases. J Am Vet MedAssoc 1997;210:46-50.

Osborne CA, Kroll RA, Lulich JP, et al. Medical manangement of vesicourachal diverticula in 15 cats with lower urinary tract disease. J Small Anim Pract 1989;30:608-612.

Bartges JW, Barsanti JA. Bacterial urinary tract infections in cats, in Current Veterinary Therapy, ed. Bonagura JD, W.B. Saunders Co., Philadelphia, 2000, 880-883

Chew DJ, Buffington CA, Kendall MS, et al. Urethroscopy, cystoscopy, and biopsy of the feline lower urinary tract. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 1996;26:441-462.

Kruger JM, Osborne CA. The role of uropathogens in feline lower urinary tract disease. Clinical implications. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 1993;23:101-123.

Kruger JM, Osborne CA. The role of viruses in feline lower urinary tract disease. J Vet Intern Med 1990;4:71-78.

Kruger JM, Osborne CA, Goyal SM, et al. Clinicopathologic and pathologic findings of herpesvirus- induced urinary tract infection in conventionally reared cats. Am J Vet Res 1990;51:1649-1655.

Osborne CA, Kruger JM, Lulich JP, et al. Feline matrix-crystalline urethral plugs: A unifying hypothesis of causes. J Small Anim Pract 1992;33:172-177.

Lekcharoensuk C, Osborne CA, Lulich JP. Evaluation of trends in frequency of urethrostomy for treatment of urethral obstruction in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2002;221:502-505.

Buffington CA, Teng B, Somogyi GT. Norepinephrine content and adrenoceptor function in the bladder of cats with feline interstitial cystitis. J Urol 2002;167:1876-1880.

Westropp JL, Buffington CA. In vivo models of interstitial cystitis. J Urol 2002;167:694-702.

Westropp JL, Kass PH, Buffington CA. Evaluation of the effects of stress in cats with idiopathic cystitis. Am J Vet Res 2006;67:731-736.

Westropp JL, Welk KA, Buffington CA. Small adrenal glands in cats with feline interstitial cystitis. J Urol 2003;170:2494-2497.

Buffington CA, Pacak K. Increased plasma norepinephrine concentration in cats with interstitial cystitis. J Urol 2001;165:2051-2054.

Lane IF. Pharmacologic management of feline lower urinary tract disorders. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 1996;26:515-533.

Lane IF, Bartges JW. Treating refractory idiopathic lower urinary tract desease in cats. Vet Med 1999;94:633-642.

Barsanti JA, Shotts EB, Crowell WA, et al. Effect of therapy on susceptibility to urinary tract infection in male cats with indwelling urethral catheters. J Vet Intern Med 1992;6:64-70.

Barsanti JA, Finco DR, Shotts EB, et al. Feline urologic syndrome: further investigation into therapy. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 1982;18:387-390.

Osborne CA, Kruger JM, Lulich JP. Prednisolone therapy of idiopathic feline lower urinary tract disease: a double blind study. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 1996;26:563-569.

Markwell PJ, Buffington CA, Chew DJ, et al. Clinical evaluation of commercially available urinary acidification diets in the management of idiopathic cystitis in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1999;214:361-365.

Gunn-Moore DA, Shenoy CM. Oral glucosamine and the management of feline idiopathic cystitis. J Fel Med Surg 2004;6:219-225.

Chew DJ, Buffington CA, Kendall MS, et al. Amitriptyline treatment for severe recurrent idiopathic cystitis in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1998;213:1282-1286.

Griffin DW, Gregory CR. Prevalence of bacterial urinary tract infection after perineal urethrostomy in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1992;200:681-684.

Osborne CA, Caywood DD, Johnston GR, et al. Feline perineal urethrostomy: a potential cause of feline lower urinary tract disease. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 1996;26:535-549.

Osborne CA, Caywood DD, Johnston GR, et al. Perineal urethrostomy versus dietary management in prevention of recurrent lower urinary tract disease. J Small Anim Pract 1991;32:296-305.

Chew, D. J., Bartges, J. W., Adams, L. G., et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial of pentosan polysulfate sodium for treatment of feline idiopathic (interstitial) cystitis. J Vet Intern Med 2009;23:690 (A).

Gunn-Moore DA, Cameron ME. A pilot study using synthetic feline facial pheromone for the management of feline idiopathic cystitis. J Fel Med Surg 2004;6:133-138.

Buffington CAT, Westropp.J.L., Chew DJ, et al. Clinical evaluation of multimodal environmental modification (MEMO) in the management of cats with idiopathic cystitis. J Fel Med Surg 2006;8:261-268.

Newsletter

From exam room tips to practice management insights, get trusted veterinary news delivered straight to your inbox—subscribe to dvm360.