Inflammatory airway disease: When, how to perform a bronchoalveolar lavage

A BAL should not be performed on a horse with overt respiratory distress, tachycardia or pulmonary hypertension.

Inflammatory airway disease (IAD) describes an interrelated set of diseases of the lower airway of horses that encompasses infectious, inflammatory, obstructive, hyper-reactive and allergic etiologies.

Clinical signs and physical findings of IAD may be overt and include respiratory distress, tachypnea, cough, mucoid nasal secretions, nasal flaring, abdominal lift on expiration and the presence of adventitious sounds (i.e., crackles or wheezes). However, often the signs are subtle and obscure, only manifesting as reduced performance or prolonged recovery after exercise.

A bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) is a diagnostic test that is easy to perform in the field and provides specific information about the presence of lower airway disease in horses.

In this article, we will discuss indications for performing a BAL, how to do it and interpret your results.

Why perform a BAL?

There are two major ways to retrieve a sample of fluid from the lower airway of the horse: transtracheal or endotracheal.

In either procedure, saline is instilled into the lower airway and a sample is aspirated. With the trans- tracheal aspirate or wash (TTA or TTW) procedure, the hair over the mid to distal cervical trachea is clipped and the skin is surgically prepared. After local instillation of subcutaneous lidocaine, a sterile, bevel-tipped cannula is inserted through the trachea, serving as an entrance guide for a sterile catheter that is subsequently used to instill the saline.

The main advantage to a TTA is that the sample was instilled and retrieved under sterile conditions; thus it is the preferred method when a culture of the aspirate is indicated.

The main disadvantages of a TTA are that the hair is clipped and the trachea is invaded percutaneously. Since the procedure recovers fluid from within the trachea, the cyto- logy may not truly reflect disease of the smaller airways until that disease process is severe.

In the endotracheal method, saline is instilled either through a bronchoscope that is passed into the level of the trachea, or 3 m endoscope or long flexible BAL tubing (3-m length, 10-mm OD silicone tube; BAL catheter by Bivona Medical Technologies, Gary, Ind., or Cook Veterinary Products Inc., Bloomington, Ind.) that is passed further to the level of the segmental bronchi, via the nasopharyngeal passage (Photo 1).

Subtle signs: IAD may be hard to detect at times, perhaps manifesting as slow recovery from exercise.

The main advantage to the endotracheal procedure is that, with long tubing such as the BAL catheter, the small airways and alveoli can be reached and cytologic examination may more accurately reflect those areas.

A BAL is particularly helpful when looking for subtle disease of the small airways. If using a 3-m endoscope for the lavage, the scope may be directed into either the right or left main stem bronchus.

When "blinding" (passing a BAL tube from the nasopharynx), the tube typically ends up in the right dorsal lung lobe; thus focal small-airway disease in other regions may be missed.

How to do a BAL

A BAL should not be performed on a horse with overt respiratory distress, tachycardia or evidence of pulmonary hypertension.

The BAL tubing is sterile and can be resterilized between patients; however, since the procedure involves passing the tubing through the upper airway, retrieved samples are not sterile and culture results will not be accurate.

Horses will cough violently during the BAL procedure, and thus moderate to heavy sedation with xylazine (250 to 400 mg/1,000 pounds body weight IV) or detomidine (3 to 10 mg/1,000 lbs IV) is needed. Addition of butorphanol (3 to 5 mg/1,000 pounds IV) or 450g of inhaled albuterol may also help suppress the intensity of the cough reflex. In some patients a twitch may be necessary.

Before the BAL tube is passed, the cuff should be checked, and a small amount of sterile lubricant should be applied to the tip.

The BAL tubing is passed through the nasopharynx via the ventral meatus using the same technique as when passing a nasogastric tube. When the BAL tubing reaches the level of the laryngeal orifice, instillation of 10 to 20 ml of 0.3 percent to 0.5 percent warm lidocaine may ease the intensity of the gag and coughing reflex.

Photo 1: A 3-m bronchoalveolar tube. The cuff at the distal tip was checked by inflation with 5 ml of air at the injection port (syringe) prior to using.

Extension of the head will facilitate passage of the BAL tube from the pharynx into the trachea. The tubing is advanced slowly until it wedges in the small airways (noted by gentle resistance). Some individuals will also instill an additional 10 to 20 ml of 0.3 percent to 0.5 percent lidocaine when the tube reaches the level of the carina.

Once the tubing is wedged, the cuff is inflated (typically about 5 ml of air) and the tube is held securely at the nares. At this point, approximately 250 ml of warm isotonic (0.9 percent) saline is rapidly infused into the BAL tubing. One may accomplish this either by bolusing 60 ml luer-tipped syringes of saline or by attaching a 500-ml to 1-liter bag of saline to a fluid administration set and applying pressure to the exterior of the bag manually or with a fluid bag pressure sleeve (Photo 2). Wait 5 seconds, and then aspirate fluid, using 60-ml syringes.

Photo 2: A fluid pressure sleeve may be used to instill the saline through the BAL tubing.

The aspirated fluid should appear foamy from the presence of surfactant. Not all of the instilled fluid will be recovered, but typically at least 50 percent of it is retrievable. A second aliquot of 250 ml of saline is instilled and aspirated. Subsequently, all sets of the aspirated fluid are pooled. The cuff should then be deflated and the tubing removed.

Serious complications associated with the BAL procedure are rare, though intense coughing in horses with pulmonary hypertension may result in clinically significant hemorr- hage from pulmonary vessels. A transient low-grade fever or mild depression after a BAL also are reported rarely.

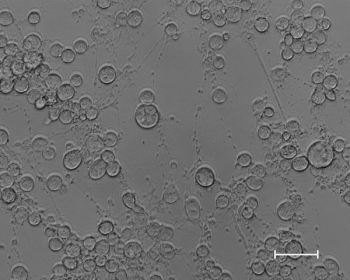

Figure 1: Cytology of BAL fluid from a young horse with inflammatory airway disease. 1=macrophage, 2= lymphocyte, 3= neutrophil, 4=eosinophil.

The pooled fluid should be mixed gently by swirling, and aliquots (approximately 10 ml) of the pooled fluid should be transferred to EDTA tubes for laboratory analysis.

If a clinical pathology laboratory cannot process the samples within a few hours of collection, the sample should be placed on ice or refrigerated.

Although the protein in the surfactant should be sufficient to preserve the cells, delayed processing can significantly affect cell morphology and thus addition of serum (10 percent v/v), an equal volume of ethyl alcohol or an equal volume of 100-proof vodka is indicated.

Figure 2: Cytology of BAL fluid from a horse with recurrent airway obstruction. 1=macrophage, 2= mast cell. There is an Alternaria spore within one of the macrophages (arrow). The presence of fungal spores is not unexpected in horses with inflammatory lung disease because the inhaled spores become trapped within excessive mucus secretions and inflammatory debris.

If laboratory processing will be delayed more than 24 hours, preparation of air-dried samples is recommended. Because of the dilutional effect of the saline, BAL samples must be cytocentrifuged or concentrated for cytological examination.

Thus, to make a smear, first centrifuge 10 to 15 ml aliquots (600 g for 10 minutes) and decant the supernatant. Gently resuspend the pellet at the bottom of the tube with the remaining fluid using a plastic transfer pipette and transfer a drop to a clean slide. Smear the drop to a feathered edge, as is done when preparing a blood smear. The slide must be quickly air-dried by fanning. Numerous slides should be prepared because typically 500 cells or more are counted by cytologists for differential enumeration.

Figure 3: Cytology of the BAL fluid from a mature horse with intense inflammatory airway disease, represented by the predominance of neutrophils. This horse had recurrent airway obstruction (heaves) with secondary infection, as indicated by the presence of bacteria intracellularly (arrowhead) and extracellularly (arrows).

Unless you are familiar with cytology of the lower airway, BAL fluid should be evaluated by a clinical pathologist. Using the previously described collection technique, normal BAL fluid contains predominately (40 percent to 70 percent) macrophages, 30 percent to 60 percent lymphocytes, less than 5 percent neutrophils, 2 percent mast cells and 1 percent eosinophils (Figures 1-4).

Figure 4: A Curschmannâs spiral (arrow) is a coiled plug of mucus extruded from the smaller airways and is a sign of chronicity.

When a small volume of saline is instilled (< 250 ml) or if only a small volume of the saline lavage is retrieved (less than 50 percent of that instilled), the differential cell count may be affected and be less meaningful.

If the BAL tubing was not tightly wedged, respiratory epithelial cells may be present; however, the presence of large numbers of respiratory epithelial cells is expected in horses with viral infections of the respiratory tract.

As the percentage of neutrophils, mast cells or eosinophils increases above 5 percent, 2 percent and 1 percent, respectively, inflammatory airway disease should be suspected. However, it should be noted that, in mature healthy horses, up to 15 percent neutrophils could be present. In general, though, if neutrophils comprise greater than 15 percent of the BAL nucleated cell population in a mature horse, it would be considered highly supportive of a diagnosis of recurrent airway obstruction or heaves.

A predominance of lymphocytes has been reported in young racehorses with reduced performance. The etiologic origin and clinical significance of this finding is not entirely understood, though it has been suggested that increases in lymphocytes, without concurrent increases in neutrophils, mast cells or eosinophils, may represent a less intense or earlier form of respiratory tract inflammation.

Curschmann's spirals (Figure 4) are coiled plugs of mucus and cellular casts extruded from obstructed small airways and are a classic cytologic finding of chronic inflammatory small-airway disease.

Hemosiderophages may be present in horses with exercise-induced pulmonary hemorrhage. If the BAL cytology does not yield a diagnosis or yields equivocal findings, the addition of pulmonary function testing may provide further insight.

Summary

Bronchoalveolar lavage is relatively easy to perform in the field. It is the preferred means of evaluating small-airway disease, but should not be performed on patients with severe respiratory compromise.

When sepsis is suspected, a transtracheal aspirate would be the preferred diagnostic methodology.

Bronchoalveolar lavages should be promptly submitted for evaluation by a clinical pathologist.

The hallmarks of inflammatory disease of the small airways are increased mucus and an increased percentage of neutrophils, mast cells or eosinophils.

Barton is the Josiah Meigs Distinguished Teaching Professor at the University of Georgia's College of Veterinary Medicine, where she is a large-animal internist in academic practice. She received her DVM from the University of Illinois in 1985, her PhD in physiology at the University of Georgia in 1990 and became an ACVIM diplomate in 1990.

Suggested Reading

•Couetil LL et al. Inflammatory airway disease of the horse: ACVIM consensus statement. JVIM 21: 356-361, 2007.•Viel L and Hewson J. Bronchoalveolar lavage in current therapy in equine medicine 5, Robsinson NE (ed). Saunders, Philadelphia, Pa. p 407-411, 2003.

Newsletter

From exam room tips to practice management insights, get trusted veterinary news delivered straight to your inbox—subscribe to dvm360.