Key gastrointestinal surgeries: Gastrotomy

Gastrotomy is a routine and relatively safe surgical procedure with several indications, but appropriate technique is vital to preventing complications.

GASTROTOMY is a routine and relatively safe surgical procedure with several indications, but appropriate technique is vital to preventing complications. For general perioperative considerations when performing this procedure, including diagnostic testing, patient monitoring, and postoperative support, please see the symposium introduction.

INDICATIONS

The most common indication for gastrotomy in dogs and cats is foreign body removal, particularly if objects are not amenable to endoscopic extraction because of their shape or size or because they have become fixed within the tissues (Figure 1).1-4 For example, surgically removing sharp foreign bodies is recommended because of the risk of perforation; linear foreign bodies that anchor in the pylorus also require surgical extraction.4,5 Foreign bodies in the distal esophagus can often be safely removed with forceps inserted through the lower esophageal sphincter via a gastrotomy, reducing the risks of pneumothorax, dehiscence, and leakage that have been commonly associated with thoracic esophagotomy.1,6 Gastrotomy has also been used to explore the gastric lumen and to decompress and evacuate the stomach of air and contents before repositioning in dogs with gastric dilatation or gastric dilatation-volvulus.1,2,7-10

Figure 1. A gastric foreign body in a dog that ingested a polyurethane adhesive (Gorilla Glue).

Gastrotomy is a safe and effective way to collect full-thickness gastric biopsy samples of lesions that may be missed or misdiagnosed with endoscopic sampling.1,2,11,12 For example, gastrointestinal lymphoma arising from deeper layers of the submucosa can cause many of the same superficial inflammatory lesions as lymphocytic-plasmacytic gastroenteritis.11 Phycomycosis can only be definitively diagnosed with organism identification by fungal culture or by special histologic stains of fibrotic, firm tissues obtained from surgical incisional biopsy. Full-thickness incisional biopsy is also required for histologic examination to definitively diagnose gastric carcinomas.1,11,12

TECHNIQUE

Make a ventral midline abdominal incision from the xiphoid to the caudal abdomen. Incisions that are farther cranial may penetrate the diaphragm, inadvertently causing a pneumothorax. Retract the abdominal wall with a Balfour retractor to expose the cavity, and perform a thorough exploration of the abdominal contents. Visually inspect and palpate the stomach for masses, thickening, or foreign bodies, and evaluate the pylorus for abnormalities.

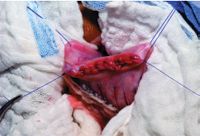

Figure 2. Isolate the stomach with moistened laparotomy pads, and place stay sutures at either end of the proposed incision in the least vascular portion of the gastric body.

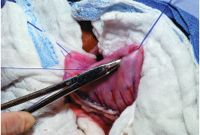

If no gastric wall lesions are present, a gastrotomy is usually performed midway between the lesser and greater curvatures of the stomach, where the vasculature is less prominent.1,3,10 Elevate the stomach with full-thickness stay sutures or Babcock forceps at either end of the proposed incision site to improve visualization of the surgery site and reduce gastric content spillage (Figure 2). If no assistant is available, drape the hemostats holding the stay sutures over the Balfour retractor to provide retraction (Figure 3). Place moistened laparotomy pads around the stomach to limit peritoneal contamination.

Figure 3. To provide traction, drape the hemostats holding the stay sutures over the Balfour retractor.

Make a stab incision into the gastric wall with a No. 10 blade. Often the mucosa will retract from the blade and will need to be incised separately to enter the gastric lumen. Extend the incision with Metzenbaum or Mayo scissors (Figure 4).1,3 Remove liquid gastric contents with suction by using a Poole suction tip to decrease the risk of contamination from spillage. Food and other large-particulate matter may clog the aspirator, necessitating manual removal or the passage of a large-diameter orogastric tube. In patients with generalized disease (e.g. inflammatory bowel disease), biopsy samples can be removed from the margin of the gastrotomy site with dissecting scissors. Do not handle the samples with thumb forceps, which can damage the tissues.

Figure 4. A full-thickness incision made in the gastric body midway between the lesser and greater curvatures.

If necessary, the gastric incision can be enlarged to extract foreign bodies and to allow thorough examination of the gastric mucosa and lumen. An index finger can be inserted through the pylorus to check patency and diameter. If a distal esophageal foreign body is present, gently insert blunt-ended forceps (e.g. Carmalt or sponge forceps) through the lower esophageal sphincter to grasp the foreign body. If the foreign body cannot be easily retracted into the stomach, incise the diaphragm, and with one hand in the thorax, manipulate the foreign body within the esophagus while attempting to grasp the object with the transgastric forceps. Thorough endoscopic examination of the esophagus can be performed after a difficult foreign body extraction to determine the extent of the trauma. Insufflation during endoscopy may result in tension pneumothorax in animals with esophageal perforation, so be prepared to perform thoracocentesis or place a chest tube.

Figure 5. To start the closure, take a bite at one end of the incision and tie it. Leave the tag long and secure it with a hemostat.

The gastric incision is usually closed in two layers with synthetic, monofilament, absorbable suture to reduce intraluminal bleeding and form a secure seal.3 The first suture layer should appose mucosa with a continuous suture pattern to prevent postoperative hemorrhage. This suture will be rapidly covered during the healing process and, therefore, become isolated from digestive degradation.3 Closure can be full-thickness or only incorporate mucosa. The second suture layer should include serosa, muscularis, and submucosa in an inverting Lembert or Cushing suture pattern with 2-0 or 3-0 monofilament absorbable suture.1,10,13 Tapered needles are recommended for use in the stomach since they pass through the wall easily and are less traumatic.3

Figure 6. Close the mucosa with a simple continuous suture pattern, and tie the suture at the opposite end.

For rapid closure, take an initial bite of stomach wall perpendicular and just beyond the end of the mucosal incision. Tie a knot in the suture, leaving the tag long (Figure 5), and secure the tag with a hemostat. Then close the mucosa with a simple continuous or running mattress suture pattern, ending just beyond the incision (Figure 6). Once the first layer is closed, continue back with the same suture in a Cushing or Lembert suture pattern, and tie to the initial suture tag (Figures 7-10).3 Omentum can be tacked over the incision site with a few simple interrupted sutures for added security against leakage.

Figure 7. Invert the seromuscular layer with a Cushing suture pattern, taking bites parallel to the incision line that do not penetrate the lumen.

Patients that have had a diaphragmatic incision will require diaphragmatic closure and removal of intrathoracic air by transdiaphragmatic thoracocentesis or the placement of a chest tube. In some patients, the chest tube can be placed through the diaphragmatic incision, which is then closed in a continuous suture pattern. Once the diaphragm is closed, aspirate the tube until the chest is emptied of residual fluid and air. Then pull the tube before abdominal closure. Patients with diaphragmatic incisions will require close monitoring for respiratory complications after surgery.

Figure 8. As you tighten the Cushing suture pattern, invert the mucosa with the needle holder.

COMPLICATIONS

Postoperative complications of gastrotomy are uncommon when tissue viability and quality are normal.3 Healing can be compromised, however, with marked gastric wall disease or neoplasia. Peritonitis secondary to intraoperative contamination, incisional dehiscence, and tissue necrosis are the most severe complications but are rare if proper surgical techniques are used. Because of the stomach's rich blood supply and collateral circulation, dehiscence is rarely a problem, particularly if two-layer closures are used. Obstruction after two- or three-layer gastrotomy closure is rare but has been reported secondary to reactions from polypropylene suture and to excessive inversion near the pylorus.14

Figure 9. Tie off the Cushing suture pattern to the original knot end.

If persistent postoperative vomiting occurs, rule out additional foreign bodies or tissue obstruction by using endoscopy or gastric contrast radiography. Animals that have swallowed foreign objects containing metals such as zinc or lead may continue to decline after surgery because of the toxic effects of these compounds.15-17 Postoperative chelation therapy is recommended in these patients.17

Figure 10. For added security, oversew the site with a Lembert suture pattern.

Elizabeth Shuler, BS

Karen M. Tobias, DVM, MS, DACVS

Department of Small Animal Clinical Sciences

College of Veterinary Medicine

The University of Tennessee

Knoxville, TN 37996-4544

REFERENCES

1. Fossum TW. Surgery of the digestive system. In: Small animal surgery. 2nd ed. St. Louis, Mo: Mosby, 2002;337-340.

2. Hall JA. Diseases of the stomach. In: Ettinger SJ, Feldman EC, eds. Textbook of veterinary internal medicine. 5th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders Co, 2000;1159-1177.

3. Rasmusen LM. Stomach. In: Slatter D, ed. Textbook of small animal surgery, 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders Co, 2003;592-618.

4. Hunt GB, Bellenger CR, Allan GS, et al. Suspected cranial migration of two sewing needles from the stomach of a dog. Vet Rec 1991;128:329-330.

5. Felts JF, Fox PR, Burk RL. Thread and sewing needles as gastrointestinal foreign bodies in the cat: a review of 64 cases. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1984;184:56-59.

6. Haragopal V, Suresh Kumar RV. Surgical removal of a fish bone from the canine esophagus through gastrotomy. Can Vet J 1996;37:156.

7. Kerpsack SJ, Birchard SJ. Removal of leiomyomas and other noninvasive masses from the cardiac region of the canine stomach. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 1994;30:500-504.

8. Sheard AL, Harrington MG. Gastric dilatation in a bulldog. Vet Rec 1990;127:291.

9. Thomas RE. Gastric dilatation and torsion in small or miniature breeds of dogs—three case reports. J Small Anim Pract 1982;23:271-277.

10. Welch JA. Surgery for gastric neoplasia. In: Bojrab M, ed. Current techniques in small animal surgery. 4th ed. Baltimore, Md: Williams & Wilkins, 1998;214-215.

11. van der Gaag I, Happe RP. Follow-up studies by peroral gastric biopsies and necropsy in vomiting dogs. Can J Vet Res 1989;53:468-472.

12. Grooters AM, Sherding RG, Johnson SE. Endoscopy case of the month: chronic vomiting and weight loss in a dog. Vet Med 1994;89:196-199.

13. Pavletic MM. Gastrointestinal surgery. In: Lipowitz A, ed. Complications in small animal surgery. Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, Md: 1996;365-398.

14. Bright RM, Jenkins C, DeNovo RC. Pyloric obstruction in a dog related to a gastrotomy incision closed with polypropylene. J Small Anim Pract 1994;35:629-632.

15. Meurs KM, Breitschwerdt EB, Baty CJ, et al. Postsurgical mortality secondary to zinc toxicity in dogs. Vet Hum Toxicol 1991;33:579-583.

16. Williams JH, Williams MC. Lead poisoning in a dog. J S Afr Vet Assoc 1990;61:178-181.

17. Nicholson SS. Toxicology. In: Ettinger SJ, Feldman EC, eds. Textbook of veterinary internal medicine. 5th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders Co, 2000;357-363.