Lung auscultation and sick calf management (Proceedings)

This morning we're going to talk about our least favorite topic – sick cattle. Sick cattle are not fun to deal with, but we're always going to have some of them.

This morning we're going to talk about our least favorite topic – sick cattle. Sick cattle are not fun to deal with, but we're always going to have some of them. I want you to understand that our philosophy should be to invest time at strategic points of the production cycle to reduce time spent at hospitals.

For the students, if there is one piece of advice to give you that the AVC has taught me. Surround yourself with people much more intelligent than you are. You'll see people like Drs. Lynn Locatelli, Wade Taylor, Doug Ford, and Paul Ritter who spend time trying to bring some form of organization to some of my scatterbrained thoughts. These are examples of people who challenge me every day. Surround yourself with these kinds of people.

This topic is very complex. Sick cattle management has paradigms within feedlot medicine. The vast majority of pulls on our database would be grouped into a respiratory disease complex. All these animals that come out of the pen are outliers on both ends of the biological curve. Very few animals come out of our pens that are in the middle of the biological curve. We need to understand why some cattle become ill and others flourish. Colostral transfer issues, trace mineral deficiencies, immunosuppression are examples of issues that explain lack of disease resistance. We have other animals on the other end of the biological curve that come to the hospital because they've absolutely been selected to gain 6 lbs. per day and have less resistance to disease. We need to understand the animals that arrive in our hospital situations and be willing to address diagnostic issues.

I have a list of management, head cowboys, head hospital people, assistant managers and so forth. These are the people who demand our profession to give them the information, the skills, the products, the tools to let them absolutely take care of every sick animal like they owned it. They take care of every animal in that feedyard like they went to the bank and borrowed money to buy it. They take care of every animal so that if the owner drives in and has a look that they will be absolutely impressed about what ishappening.

Pen riders make the difference

Our plan is to help you understand that sick cattle management begins when the truc backs up to the chute with new arrivals. Sick cattle management begins in the home pen. Recognizing pulls early in disease and ability to remove those cattle from the pen in a voluntary fashion becomes very important. The front line of sick cattle management is the people who are out there riding pens. It's important we stretch their job description far beyond what it was 10 years ago. Pen rider focus at this point is to encourage modulation of prey-animal instincts. In order to do that these people have to be aware of prey animal instincts and understand new cattle acclimation. The goal when unloading cattle is to convince cattle to be confident of their new home and willing to visit the bunk.

What is really important is that the stage of respiratory disease that arrives at ourhospital depends on cattle sensitivity and level of trust cattle have for that caregiver.We've wondered why in these commingled calves you'd have a relatively insensitiveanimal, a little black baldie from Ogallala Neb. that would be out in his home pen withhis head almost on the ground. When you brought him in the hospital his temp was a104.8, his lungs were normal, but he looked terrible. He really was in pretty good shape.In contrast, there's a little red hound-gutted Limousin-cross calf that looks pretty good in the home pen and something catches your eye and you bring him in. His temp was 105.2° a couple of days ago and now is 103.6° and his lung is very congested with advanced respiratory disease. Why the difference? It's because of the variation in cattle sensitivity and our inability to recognize sentinel animals on arrival and interact with these sensitive herd members. These people need to expand their job descriptions to include learning to train cattle and acclimate them from minute one.

It's important that we're able to pull a febrile or depressed animal out of a pen prior to the development of serious lung pathology. An example of that would be someone who can interact with the abnormal animal, ask him to volunteer to leave the pen very efficiently without disturbing pen mates, so the caregiver can return to the pen and request these animals to communicate their state of health.

Take the example of a Charolais calf looking at a pen rider who wants to take himto the drovers alley. The pen rider is polite to the pen mates and confident that he can communicate with this animal without upsetting pen mates. With pressure and release, position and the ability to communicate with the animal, he can ask the animal to gently and quickly leave the pen and wait to go down to the hospital to be examined. That is critical. Not only the success of the treatment of that particular individual but to leave a situation where you can go back in and evaluate the health of the pen mates.

Prey vs. predator

We're just starting to understand the relationship between horsemanship and stockmanship. Any time we have pen riders going into pens with horses with the wrong posture we've lost potential. A horse with a switching tail and his ears moving back and forth immediately tells the other prey animals that "I'm not sure this rider can be trusted." I think this is something we need to work on with our pen riders. The relationship between horsemanship, stockmanship and these kinds of health issues are very important.

What got me interested in what Bud Williams teaches is that some cattle that arrive at the hospital with advanced lung damage are not missed pulls. You all have seen a lot of these cattle that you've noticed as you went though the yard after the pen rider has gone through the pens. These are animals I've photographed out of the pickup after we've had experienced pen riders go through these pens. What I want us to understand is my consternation toward those pen riders has been absolutely replaced with consternation toward myself for taking 35 years to figure out that I did not instruct them correctly in communicating with the cattle. It was not their fault. No one had ever told them. Why would these animals communicate with me in my pickup or a feed truck driver? It's obvious. They don't consider me a threat and are very willing to communicate their true state of health to me. These are not mispulls. These late pulls are cattle that do not trust handlers enough to communicate early signs of respiratory disease.

Concealing weakness

These kinds of examples make us realize that we have to start understanding the most important prey animal instinct. — concealing weakness. The reason we still have cattle and horses on this planet and the dinosaurs are gone is that cattle and horses know that no predator is going to pick on the fastest, strongest, healthiest animal in the group. They are going to pick on the feverish, lame, old prey animal first. We will never convince cattle or horses that we are not predators. That is not the intent. Our intent is to convince cattle and horses that we can be trusted and looked to for leadership.

These pictures were taken 10 seconds apart. The Charolais calf had his eyes shut, was salivating, breathing fairly rapidly, and had his head almost level with his torso. He had not been eating, but the minute he thought I was in the pen his appearance changed. These cattle deserve an Academy Award. They can act.

Here's a story that makes it clear. You've all unloaded lame cattle but you didn't notice they were lame until day three and you blamed your processors. We unloaded 700 cattle last week and as they came off the truck you can see quarter-sized defects in the side of their hoof walls. They were putting 100% of their weight on those feet. They were so sure I was a predator or the people unloading them were threats, they would put 100% of their weight on the injured foot. The next morning weight-bearing was reduce to 30%. Cortisol and adrenalin can hide lameness.

A load of calves delayed by a blizzard arrived with blood along the side of the trailer and an amputated claw frozen to the aluminum. The trucker asked if we could identify and document him on the load, but there was not a single calf limping. The only way he was identified was that he left a bloody track in the snow with his hind foot. The calf was sorted off, bandaged and placed in a stall. He was non-weight bearing by morning.

The point is that if this instinct is strong enough to conceal the loss of a toe, it's no mystery that he'd hide a temp of 104.8° from a pen rider or IBR in the trachea or congestion in the lung. These are the things we need to concentrate on as we educate our pen riders and caregivers.

As new arrivals are acclimated correctly, the pen riders start to understand that each of those animals is an individual. They will learn to interact with them and be able to understand that each of them prefers to be worked at a specific distance. As an animal is selected to go to the hospital, it should be a positive experience for the horse, caregiver, the calf and his pen mates.

Notice the tiny signs

I used to tell my pen riders that sick cattle will avoid them and that they have to look in the back of the pen for sick cattle. That's absolutely true if sick cattle or all cattle consider you a threat. Our goal is to work with these animals from day one to convince them to communicate sickness instead of hiding it. Our goal is that as a pen rider goes through the pen two or three calves follow him around looking for antibiotics. When you get to that point, not only does he pull cattle in a lot earlier stage of disease, they will group themselves. If you see one, you'll see two or three.

Discussion of antibiotic performance and response rates should be qualified by a clear description of the pathology involved.

We all have been guilty of thinking that every animal that is hollow, weak and depressed that comes to the hospital has respiratory disease. It is possible to have gaunt, depressed cattle arrive at feedyard hospitals with no respiratory disease. These "noneaters" can be single cattle scattered in pens of new cattle or can be entire pens. Pen riders need to recognize these cattle early in the feeding period.

Welcome to the feedlot

This is an example of healthy yearling cattle with average dry matter intakes at 7.5 lbs. at day 8 in the feeding period. They were low-risk Herefords that came from Oklahoma to Kansas. A few dominant cattle were the only cattle willing to drink from the tank on the mound. The timid pen members were not willing to compete at the tank and stood huddled in the back corner of the pen trying to tell caregivers that they hated their new home. Don't be afraid to change pens. Removing these cattle from their pen correctly and taking them to a new situation with temporary round tanks and new feed will result in immediate response.

I want to encourage you to see these kinds of things at 8 or 10 hours rather than 7 or 8 DOF. This is an example of these cattle at 76 DOF. When confused cattle decide to change, it's amazing what they can accomplish with compensatory gain. They gained 4.25 lbs./day for 126 days. The big surprise was this group was 93% choice. There are Hereford cattle in this world that are absolutely fabulous.

My question is: who causes a particular animal to not eat or drink? It's a group effort. A lot of it happens because the rancher gathers them, takes good care of them up until 870 lbs. then something changes on the day they ship. He brings the neighbors over and they work together to scare and cripple them. It could happen at the sale barn, too. Care givers that understand how to unload cattle during feedyard arrival can reduce the risk on noneaters. It's very important to say hello to these animas and take them to their home pen in a manner that will convince them that the feedlot is a better place to be than the Flint Hills of Kansas. These are the things we need to teach our people and all of the sudden that changes the way they handle sick cattle.

Evaluating animals in the hospital

What got me interested in extending diagnostic efforts would be this whole idea that managing disease based on undifferentiated fever has always made me a little nervous. Looking at research, treatment responses and mass-treatment responses based on undifferentiated fever really bothers me. Dr. Dan Thomson showed the Mycoplasma information and 51% of those cattle that died never had a fever above 104°. If we would have treated based on temps of 104°, there would be missed opportunities.

Some of our computer health systems furnish reports that have case fatality rate vs. initial pull temp. These reports indicate poor correlation between initial pull temp and case fatality rate. I think we need to evaluate this and ask why that might be. Some feedlot crews do a poor job of temping cattle.

Think about how and why we do these things. The lack of correlation in some groups of animals led us to expand on our philosophies on what to do with animals as they come to the hospital. I think it's important that individual animal examination can identify cattle with serious lung pathology and guide treatment decisions and more importantly predict treatment response.

Start with a stethoscope

Invest time examining each individual animal. Ask treatment teams to take temps, but explore the fact that there is variation in lung pathology in cattle pulled for signs of respiratory disease. I asked half a dozen of our operations to at least consider use of the stethoscope in the hospital. These people had never used a stethoscope in their life. What amazed me is that they understood that there would be no way to make a decision in the hospital on sick animals until they understood the range of variation in normal animals. Learn what sounds to expect in normal cattle.

Where do you start? Listen to processing cattle, lameness pulls and bullers. Start on the animals that have just been processed and get a feeling for normal in two areas of the chest. Understand what it sounds like over the mid-chest where the large airways are dividing, and then you compare those sounds, the volume and nature of them, with what it sounds like ventrally in the lung. Learning the importance of the range in normal within normal cattle versus location is really important.

Develop an expectation of lung sounds. Expect to hear mid-chest sounds very well and be able to describe those sounds. On normal animals, expect much less volume in the ventral chest. Old people like me sometimes can't even hear the sounds.

When an animal comes to the hospital and the volume at mid-chest, and the volume under his elbow is the same or louder, there's a good chance that pathology is present. Then you start thinking through and analyzing that. Your goal is to understand that you would ultimately identify active, acute, fulminating infections vs. old chronic things that have been there since the calf was branded. It's important to go through this process as cattle are treated for respiratory disease.

As people get a chance to evaluate hospital cattle, compare lung sound volume and nature they start to develop some understanding of the dynamics of disease development and healing. It would be wonderful to listen to that animal and look right in and get a glimpse of what is going on. We all need help in understanding progression of lesions.

The hospital people have taught me that the process of lung lesion development, at least related to sound, is much more dynamic than I ever dreamed. Cattle developing pneumonia exhibit drastic changes in lung sounds within 6-24 hours. Response to treatment can be monitored by improved sounds in the same length of time.

Lung scores and temperatures

Develop a lung scoring system—lung scores 1 and 2 include normal cattle. Scores 3 and 4 are mild acute pneumonia cases, scores 5 and 6 are serious, acute cases. Lung scores 7, 8, and 9 include cattle with various degrees of referred sounds indicating chronicity of lung pathology. Reserve lung score 10 for AIP cases.

It becomes very obvious that cattle arrive at feedyards that have abnormal lung sounds that happened 60 or 90 days ago. Hospital teams can decide that lung sounds are old referred sounds that will never change and are superimposed over a new respiratory episode.

As we noticed dissatisfaction with the initial pull temp vs. case fatality rate reports and were uncomfortable about the correlations there, our goal then was to score some of these lungs and look for correlations between initial lung score and case fatality rates, retreat rates, and treatment costs. Our dream was to expect correlation between lung score, case fatality rate, retreat rate and treatment cost. If this kind of information would help strengthen treatment decisions, our expectations would be to seek correlation between lung score and these other three measurements.

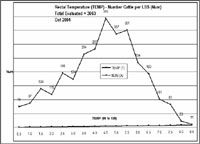

As an example, I have data that show the pulls at a hospital. The cattle description was predominately 450 to 550-lb. beef cattle from the southeast arriving in a Nebraska feedyard in the fall. That's predominately what the hospital traffic included. Some of the animals were mass treated on arrival and some not.

The first table lists lung scores from 1 (normal) to 10 (severe) of respiratory pulls, the number of cattle in each category, and eventual case fatality rate. The second table includes the same cattle listed by initial pull temp and eventual case fatality rate.

As we did a regression analysis you can see that the R2 with lung score vs. case fatality rate was .70 The R squared value of initial pull temp vs. case fatality rate was.25 The lung scores arriving at the hospital allow a measure to evaluate pen riders—early pulls respond more effectively.

This kind of data is specific for a certain group of people at a certain stage of training and a certain class of cattle with a certain endpoint and expected feeding period. I think that is important to know. Review pull temperatures at hospital arrival. The vast majority of the cattle were pulled at 104.5° to 105°.

Learn to use four important tools in sick cattle management. The most important tool are the eyes and mind of a highly trained pen rider. Be willing to use the stethoscope and thermometer to evaluate pulls and then rely on the eyes and mind of hospital and treatment caregivers.

Caregiver communication

What I'd like to visit with you about is whether or not lung auscultation can strengthen treatment decisions and result in more cost-effective and prudent antibiotic use. We need to apply these not only in our hospital, in our daily work, but also in our research facilities. As we look at response rates and research and first treatment success rates on cattle pulled with a lung score of 1 vs. those with a lung score of 5, our impression of that antibiotic and our expectation of that antibiotic could be very different.

As the pen rider brings animals out of the pen and requests they be temped or goes on and does this on his own, I think there is potential for the stethoscope to empower treatment decisions with or without a thermometer.

There's some potential for this technology to guide pen management early in respiratory outbreaks. If we have a pen of new calves and we pull five out of 100 and take them to the hospital and all of them have normal lung sounds, our perception of the status of that pen may be different than if we take five down to the hospital and all of them are lung score 6 already.

Our goal is to create communication between hospital crew and pen riders. This is so variable. I have been to feedyards where pen riders will bring 25 pulls down to the hospital and leave no written information on why the cattle were pulled. Other pen rider crews arrive at the hospital with pulls listed by lameness descriptions or predicted pull temperatures and lung scores related to respiratory pulls.

Create and absolutely instill communication between pen riders and treatment teams. It is important that the pen rider empowers the treatment crew and the treatment crew sends information back almost immediately. What were the temps of my pulls today in each of those pens? How did the lungs sound? When were they processed? What are their feed intakes? That is the definition of caregiver communication. As Clint Hoss acclimates these new calves and trains them to go to the bunk and gets them to work as a confident herd, all of the sudden it changes what his perceptions are of how to look for sick cattle.

As new cattle are acclimated, pen riders can not rely on response to feed delivery to find sick cattle. All calves will go to the bunk whether they eat or not so pen riders need to ask calves to file by handlers for health evaluation. Relative to sick cattle management, it's important that we work as a team and communicate the pen riders perception to the treatment crew. As we learn to refine our observation or diagnostic skills within an operation, share those observations with eachother.

Observation skills

I have an example of two animals that came to the hospital a couple of weeks ago. One calf has a temp that is 106.2° and a pen mate's initial pull temp was 105.2°. This is pretty early in the morning. Both of them were obviously different than their pen mates, both of them were a little sleepy-eyed and tended to be a little unstable in their hindquarters. Our team examined these animals at 6:30 in the morning with an ambient temperature of 68°. One calf with lung score 1 and a temperature of 106 had normal lung tissue was obvious at postmortem exam. The patient with lung score 5 and temperature of 105.2 displayed obvious gross pathology of severe acute pneumonia in the right apical and cardiac lobes confirmed by histopathology and culture results. These differences in these pulls could bepredicted by lung scores.

Prudent antibiotic use

Do these cattle deserve the same antibiotic treatment?

Stethoscopic evaluation is impossible when cattle are held with maximum chut pressure. Asking people to at least investigate this technology encourages them to do a couple of things that can help treatment response. It's important to release the pressure on the side of he chute so sick cattle can breathe.

This will encourage people to have some respect for the sick animals and howt hey run the chute, how they observe them. Touching sick cattle with a stethoscope encourages treatment teams to notice differences in respiratory difficulty. Handlers can palpate intercostal effort related to lung pathology.

Lung pathology was absent in one pull. Pneumonia lesions were present in the calf with lung score 5. Histopathology revealed severe changes in the grossly abnormal areas of the lung that were culture positive for bacterial pathogens. The airways were diffusely and severely expanded by degenerate junk, neutrophils mixed with debris. Multifocally these neutrophilic infiltrates spill into the surrounding alveolar areas. Where there is no alveolar infiltrates, the alveolar spaces are often atelectic. Diffusely the alveolar walls are congested and one section, the intralobular septa, are greatly expanded by fibrin and fibrin thrombi.

As you read and explain to people listening to these animals, and amplify lung sounds for them, all of the sudden the vibration and irritation within these stethoscopes start to make sense to people evaluating lung sounds. Hospital teams can identify chronic lung changes in cattle destined to be railed or retreated.

As we go through time, what is exciting is as we look at these case fatality rates and antibiotic response relationships, all of the sudden you can decide if we can treat all cattle with lung score below 4 with an antibiotic that costs $8 per head and get the same response as treating animals with lung scores above 4 with an antibiotic that costs $35.Our goal is that these case fatality rates be equal and that as we go through time we encourage pen riders to find more cattle with early pathology.

Our goal for this technology is to economically drive our protocol refinement. Use treatment protocols to guide treatment decisions. Teach hospital treatment crews important principles relative to pharmacology, dose, withdrawals, clearances, legality of drugs, and antibiotic responses and expect them to base treatment decisions on cattle examination. If we wait for the computer to tell us that an antibiotic is not working, how many animals have we treated incorrectly? There are pens in feedyards where antibiotic A is doing a really nice job and there's another pen where antibiotic A could be replaced with a better antibiotic. I want those people to understand that and be able to meet those kinds of situations.

Eating and treatment

We'll all have re-treat cattle. Dr. Lechtenberg talks about hospital management. We're going to have cattle that come back to the hospital for additional therapy because their ability to heal was limited by stress. Or we treated the initial treatment too late or with their wrong antibiotic or we have problems with immune competency. A lot of what we see is that we've treated animals without addressing this issue of being a non-eater. A lot of the immunosuppression is because we've not encouraged that animal to fuel himself.

A biosecurity dream is to send all respiratory pulls to a new home pen if ownership will allow. From the standpoint of biosecurity and management and sorting cattle so they will flourish, by far that is where we have the highest success. With the better computer and accounting programs we have, we have some commercial feedyards with customers willing to do that. Treated cattle don't stay together until harvest time, but they can stay there for 60 days and then some day we'll sort to send home. If we have uniformity and if we can take a time frame of respiratory cattle and make new home pens out of it it's amazing what that does for performance and retreats.

There is a mixture of cattle coming to hospitals. Some calves arrive at the feedlot and are willing to compete at the bunk and eat well. There are other calves that never were able to compete at the bunk. They become ill and go to the hospital. The calf that was willing to compete and is treated, as the antibiotic starts working, what does he do? He goes back to the bunk. Sick calves that never had the confidence to compete at the bunk will not improve until pen riders convince the recovering calf to visit the bunk. Addressing this non-eater issue in the social behavior of confined cattle is absolutely critical for complete convalescence. Dr. Lechtenberg made a very good point. I heard him say that it doesn't matter what you put in a hospital bunk unless the cattle eat it. The big issue is trying to make sure that these animals visit that bunk. Our goal is that we can detect these animals very early in disease and that we can ask cattle to be voluntarily pulled, voluntarily to leave the pen, quietly walk in the chute and stand to be examined and treated and then walk directly out of the chute and start eating and drinking.

Treat the priority cattle immediately. If the 80/20 rule ever worked, it works in a feedyard. In the feedyards I work with, at any given time 80% of the risks are in 8 or 10 pens of the feedyard. It is not uncommon for the pen riders to work for 2 hours before getting to the problem pens. By the time these calves are pulled and taken to the hospital it is lunch time and the hospital crew is not available to treat the calves. Then, something else will come up, such as shipping and sorting cattle, and calves that were sick last night are treated at 3 or 4 in the afternoon. That's silly. Our goal should be that the priority cattle are identified at daybreak and they are pulled out of the pen and are treated within 10 minutes after leaving the pen and either put on feed or water or put back home. These are goals for pulling priority cattle.

Sanitation and biosecurity

Dr. Lechtenberg talked several times about Salmonella. Dr. Taylor is always asking his people about when they get a cold and go to the hospital to be treated to think about two things – individual animal medicine and hospital care. On one hand, they might say you have a severe pneumonia and we'll give you a really potent antibiotic but you can't go home. We want you to go down in the basement of the hospital and there's a bunch of people in your state and we want you to take your clothes off and sit around on steel benches and we'll bring ice water to put your feet in and we don't want you to eat or drink. Sit down and take those antibiotics and see how fast you heal. On the other hand, from the standpoint of individual animal medicine, if I send my grandson to the doctor to be treated, I don't care if that pediatrician has looked at 50 kids that day. I want him to look at that child as an individual and I want him to think and listen and touch and examine that child just like he did the first one.

This is what amazes me about the list of people at the feedyard. Once you teach them some of these things about temperature, response, immunity, listen, touch, feel, think, all of the sudden they are very content to stand there and that 233rd sick calf they treated at 5:30 in the afternoon gets the same attention as the calf did at 7:30 a.m. It's easy for people to enjoy and excel a job they understand. That is our responsibility as a profession to do whatever we can to empower those people. Think about biosecurity. Dr. Lechtenberg did a fine job of explaining how a disease can go from tank-to-tank and pen-to-pen.

Setting priorities

Monitor treatment crews by evaluating antibiotic protocols and methods used in hospital management. Did they handle the cattle with care? Did they treat them immediately? Did they practice sanitation and biosecurity? And yes, did they select the appropriate antibiotic? They need to know that in addition to selecting the antibiotic that I left there, that effectively encouraging sick cattle to exercise, eat and drink, is just as important. Unless they understand that you have to go to hospital pens multiple times per day and demonstrate to those cattle that a human can be there and interact with them without taking them to the chute, then they are losing some treatment-response potential.

Those are investments in time that are important to treatment response. When I ask my team to hay cattle in the hospital or tell them to provide hay to the hospital cattle it used to be they would run down, get the pickup, throw three small bales in it, throw it in the bunk and go back to the coffee shop. It's okay to put the hay in the bunk but they have to understand that they are there to make sure that the animals they think need they are the first to the bunk. Never pressure or push cattle to the bunk. Take slow eaters away from the bunk area, show these thin, giant animals that have not eaten since arrival that you are there to walk with them and encourage them to eat. Sometimes timid hospital cattle never get a chance to eat hay. The aggressive cattle gobble the hay and remain dominant within the hospital pen. Create cattle confidence so timid cattle will be willing to compete as they return home.

I can never overemphasize how important it is to sort like cattle with like cattle. Use lung scores to send mild cases home and be willing to send severe cases to comfortable hospital pens for convalescence.

Do not ignore cattle in long term recovery pens. Lame cattle, cattle with castration infections, and respiratory chronics respond to exercise. Encourage caregivers to work with railer pens on a daily basis.

I forgot how massive doses of antibiotics affect the digestive system. Is it circulatory? Does it diffuse into the rumen? Dr. Upson will remind you that there are acouple of secretions in the body that have the same antibiotic concentration as the blood level. If there are high concentrations of antibiotics in the blood stream, tears and saliva have that same concentration and can affect rumen flora. I think you understand that I feel that antibiotics are really important in our treatment programs but antibiotics don't heal animals. They kill bacteria. It's up to us to teach our people to heal these animalsand give them care.

It's important to me that you know that these are not my ideas. The things we've talked about this morning come from pen riders, treatment crews and management. There are treatment crew members that have learned to use a stethoscope to efficiently strengthen treatment decisions and improve priority pen management. I appreciate support from mentors like Dan Thompson, Dee Griffin, Wade Taylor in these efforts.

Questions:

Question: You've obviously looked at case fatality rates quite a bit here. I thought I knew what they should be and lately I think I'm more confused by case fatality rates than I have ever been. How are you using them to make evaluations? I realize you have to do it by the class of cattle and type, etc., but are you using them to evaluate how well you're doing? Where do you think they should be?

Noffsinger: All I can do is compare variation in our database. You and I know that probably these are the best responses that we have. The people I talked about today are the top 30% of the clients we have. I'll tell you that over the entire feeding period our expected case fatality rate would range in the 6-8 range. We have feed yards with 1.8-2.5% case fatality rates and we have feedyards during certain times of the year it could be 21%. That's been a couple of years since we had any of those but they were possibilities.

Question: Maybe it should be case-specific fatality rates. In other words fatality rates for just BRD cases.

Noffsinger: Should it be for just respiratory cases? You're right. The data that I have there includes all those. When we look specifically at case fatality rates not connected to lung scores, then they are specific. The correlation between lung score and case fatality rate includes all causes of death. Then the databases that we use are more definitive. I think that's fair. I think if we do a bad job treating respiratory cases we take some of the oxygen metabolism ability away from those animals and it's a responsibility to watch that.

Question: Do you utilize weight changes in the evaluation of your treatment response?

Noffsinger: Absolutely. Both during the initial stay and then at retreat time. There is no debate in our organization whether it's a retreat or re-pull. If he ever has to come back to the hospital it's our fault. If he was gone from the hospital for 40 days and gained nothing we look at that differently than if he gained 4 lb./day. There was a comment about a relatively small feedyard, when they have one of these guys that won't eat, they routinely mix up milk replacer and give it to him until he starts to eat. That's really important. Dr. Lechtenberg talked about giving them the nutrients they need. Some cattle need electrolytes, some cattle don't. You shouldn't have to be giving that to him. Your goal should be that you should be able to mix a bucket of

that or put it in the tank and go out and take him to the tank and encourage him to do that on his own. Of all the handling things and all the things we teach, that is by far the most difficult. But we'll do that.

Question: Can you comment on the crews starting to take ownership of what they are doing, retention of employees, attitude, etc.?

Noffsinger: Some of the crews we've had have challenged Dr. Taylor to go way into the data month by month to tell them how they are doing. We used to ask them would you like to take responsibility of one section of the yard? They would say no. Now they want to and not only that they want Dr. Taylor to tell them what is their thousand head ridden per month, what is their pull percentage of that, what is their treatment percent, what is their dead rate. They have a golf game going on if they have an untreated respiratory pen dead. If you have the most death loss points you are the boy on the bubble and you are the one who is looked at if anything breaks down. It has drastically reduced pen rider turnover. You can't get rid of these guys. That's the best part of the whole thing.

Question: Are there differences between stethoscopes that are important to you?

Noffsinger: Yes. What people would do is buy a stethoscope for $7 and they can't hear anything. You want a good Littman stethoscope, SE2, they cost $70, and you go out and make sure it works and does what it is supposed to do, then you offer them a deal on it and keep buying new ones. They you know what they have and you can check it. That is really important. You have to make sure you have good equipment.

Question: Explain how you think about this if you have lung scores 3 and 4 and get treated with X and 5, 6, 7 get treated with Y.

Noffsinger: This will depend on the operation, but usually lung score 3 and 4 are treated with something that costs $8 per head. The others cost $43. We do the distribution for each pen rider. If pen rider 1, if all his cattle are lung score 3.5 and lower, we need to go out there with him and say that some could be okay, we need to give them another day.Rider two, if everything he brings to the hospital is 7, we need to help him do some things. As you watch their ability to sort the data, I ask it to sort antibiotic vs. lung score and you start seeing some of these trends.

Question: I'm still struggling with case fatality rates and how you are looking at those. The cause-specific case fatality rates I understand. But when you throw all causes of death into one category then try to correlate those with lung lesion scores I can't find a correlation between a lung lesion score of 2 or 6 and calving 90 days later or bloat 90 days later or whatever reason you want to come up with. It seems like that would be a much better comparison if we looked at case specific and basing the cause of death on necropsy exam which I assume that everyone is doing.

Noffsinger: I agree, absolutely. We also need to take it a step farther. We need to look at harvest. We need to go so specifically that we look at lung score 5s, what is the percentage of lung lesion that detected at slaughter, what is the loss of the oxygen metabolism, what were the rates of gain prior? I agree. There's probably not much connection between having pneumonia or having a calf, but there might be a connection of having pneumonia and being dead of AIP or bloat.

Podcast CE: A Surgeon’s Perspective on Current Trends for the Management of Osteoarthritis, Part 1

May 17th 2024David L. Dycus, DVM, MS, CCRP, DACVS joins Adam Christman, DVM, MBA, to discuss a proactive approach to the diagnosis of osteoarthritis and the best tools for general practice.

Listen