Managing difficult urinary tract infections (Proceedings)

Urinary tract infection is the most common infectious disease of dogs, affecting as many as 14% of dogs over the course of their lifetime. The majority of these urinary tract infections (UTIs) are benign and respond readily to antimicrobial therapy.

Urinary tract infection is the most common infectious disease of dogs, affecting as many as 14% of dogs over the course of their lifetime. The majority of these urinary tract infections (UTIs) are benign and respond readily to antimicrobial therapy. However, some patients with bacterial UTI do not respond to antimicrobial therapy and/or develop recurrent UTIs following withdrawal of antimicrobial therapy. Recurrence of clinical and/or laboratory signs of UTI may occur as a consequence of relapse (persistent infection), reinfection, or superinfection. Classifying recurrent UTI in this fashion is clinically useful because it provides guidance as to the possible cause for recurrent UTI (Table 1).

Relapses (persistent infections) are defined as recurrences caused by the same species and serologic strain of microorganism(s) within days to a few weeks of stopping antimicrobial therapy. In contrast, reinfections are recurrent infections caused by a pathogen different from that causing the previous infection. Reinfections are the most common form of recurrent UTI and typically occur more than a few weeks after stopping antimicrobial therapy. Superinfections are uncommon and are new infections which develop during the course of antimicrobial therapy. Urine cultures will be positive during or immediately after terminating therapy.

Confirming the Diagnosis of Bacterial UTI: Indications for Urine Cultures

A presumptive diagnosis of UTI is often based on clinical signs and urinalysis findings. Detection of pyuria and bacteriuria by urine sediment evaluation is highly suggestive of bacterial UTI. However, bacteria are often difficult to detect on a urine sediment exam and white blood cells may be present for reasons other than infection. Additionally, many patients with a compromised immune system and/or polyuria, may not have cells detectable in the urine. Therefore, basing a diagnosis of UTI solely on clinical and urinalysis findings may result in both false positive and false negative diagnoses. (Table 2)

Although commonly treated with antimicrobial agents, lower urinary tract signs in young cats typically do not result from bacterial UTI. Recurrence of clinical signs is common in these cats, but recurrence rarely results from bacterial UTI except when urinary catheterization has been performed. Likewise, recurrent signs of lower urinary tract disease may occur in the absence of bacterial UTI in dogs with urolithiasis, neoplasia, or other urinary disorders.

If a presumptive UTI does not respond to antimicrobial therapy, a urine culture is indicated. Antimicrobial therapy should be withdrawn at least three days prior to collection of the urine sample for bacterial culture. Urine samples should ideally be cultured within 30 minutes after collection to optimize results. If immediate culture is not possible, urine may be stored refrigerated for up to six hours.

Interpreting Urine Culture Results

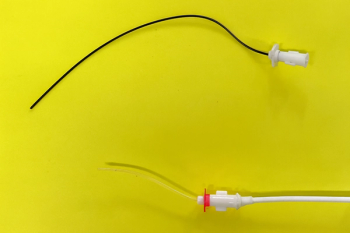

Urine for culture should be obtained by cystocentesis whenever possible because this minimizes the risk of contaminating the sample. Differentiation between bacterial pathogens versus contaminants can usually be made with quantitative urine cultures. A high bacterial count in a properly collected urine sample is evidence of UTI. Small numbers of bacteria cultured from urine of untreated patients usually indicate contamination. When bacterial numbers are in the suspicious range, the urine culture should be repeated. If the same bacterial organism is cultured in similar or greater number, infection is confirmed since contamination is unlikely to yield reproducible results.

Diagnostic Evaluation - The Key to Successful Treatment of Recurrent UTI

Patients with recurrent UTI require additional diagnostic efforts because of the increased probability that conditions predisposing to or complicating infection are present. Therapy of UTI in these patients is most likely to succeed when these conditions are recognized and corrected. Initial patient evaluation should include a review of the medical history, physical examination, urinalysis, urine culture and susceptibility testing, renal function tests (serum urea nitrogen and/or creatinine concentrations), and survey abdominal radiographs. As described above, results of previous urine cultures make it possible to establish whether recurrence is due to relapse or reinfection. If initial tests confirm the diagnosis of bacterial UTI but fail to identify the cause or type of recurrence, consider recommending a four to six week course of antimicrobial therapy as described below.

If infection recurs despite a properly performed course of antimicrobial therapy, further diagnostic efforts are indicated. Differentiating relapse from reinfection provides guidance in selecting appropriate diagnostic tests. Consider performing appropriate contrast radiographic, ultrasound and/or cystoscopic procedures to rule-out urolithiasis, neoplasia, or structural abnormalities, or involvement of the upper urinary tract. Prostatic involvement may be investigated using ultrasound examination and cytology and culture of semen or prostatic biopsies. Uroendoscopy is helpful in the evaluation of patients with recurrent urinary tract infection. Direct examination of the lower urinary tract often reveals anatomic abnormalities that may contribute to infections. It also facilitates collection of mucosal biopsies for histopathology and culture. A recent study demonstrated that culture of mucosal biopsies was more sensitive for detection of bacteria and mycoplasma compared to culture of urine obtained by cystocentesis.

Definitive diagnosis of pyelonephritis is difficult. Only bacterial isolation from renal parenchyma or urine obtained from the renal pelvis provide conclusive proof of renal infection. Pyelonephritis may be suspected on the basis of clinical or laboratory findings suggesting renal involvement. Diagnosis of pyelonephritis may be supported by: 1) finding inflammatory casts on urinalysis, 2) obtaining a positive bacterial culture from kidney or renal pelvis by fine needle aspiration, 3) renal biopsy and culture, 4) intravenous urography, or 5) renal ultrasonography.

Hyperadrenocorticism and diabetes mellitus are relatively common yet overlooked causes for reinfections in dogs. Dogs with one or both of these conditions are predisposed to UTI because of immunosuppression and reduced urine concentrating ability. Urinalysis findings are often characterized by a lack of inflammatory reaction despite the presence of bacteriuria. Many affected dogs (approximately 50%) do not have clinical signs of urinary tract disease.

Management Guidelines

Antimicrobial Selection and MIC's

Susceptibility testing should be performed on all urinary bacterial isolates from patients with recurrent UTI. As a result of renal excretion, many antimicrobial agents attain substantially higher concentrations in urine than in blood. The efficacy of antimicrobial agents in treatment of bacterial UTI is best predicted by determining the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of the bacteria isolated from the urinary tract. The MIC is defined as the least amount of an antimicrobial agent that inhibits growth of a specific species or strain of bacteria in a defined and reproducible set of in vitro conditions. Efficacy of a drug in treatment of bacterial UTI may be estimated by multiplying the determined MIC of the bacteria isolated from the UTI by four; if this product is less than the mean urine concentration for the drug, there is a high probability that the drug will be effective. The drug selected should be administered frequently enough to maintain inhibitory concentrations in urine and for sufficient time to eliminate the infecting agent from the urinary tract.

Recognition of renal or prostatic involvement is an important factor in formulating therapeutic plans for patients with recurrent UTI. Decisions concerning treatment for superficial infections of the lower urinary tract urothelium can be based on urine antimicrobial concentrations. However, it is necessary to select antimicrobial agents that attain high concentrations in serum and urine to eradicate deep seated infections such as pyelonephritis or prostatitis. Because of the blood prostatic fluid barrier is expected to be intact in chronic prostatitis, an appropriate antimicrobial which will attain therapeutic concentrations in prostatic secretions should be selected (e.g. quinolones, trimethoprim-sulfonamide combinations, chloramphenicol, clindamycin, or erythromycin).

Protocol for Therapy and Follow-Up of Recurrent UTI

Culture a urine sample collected by cystocentesis 3 to 5 days following initiation of antimicrobial therapy. Performing urine culture at this time is designed to recognize treatment failure so that a prolonged period of unnecessary and expensive antimicrobial therapy can be avoided. If bacterial growth is detected 3 to 5 days after initiating therapy, treatment should be reevaluated. If the urine is sterile 3 to 5 days after initiating therapy, treatment should be continued.

Data concerning the minimum and optimum duration of antimicrobial therapy for UTIs are not available. It is recommended that acute, uncomplicated UTIs and some reinfections be treated for a period of 10 to 14 days whereas chronic or persistent UTI should be treated for at least 4 to 6 weeks. Some infections involving the kidney(s) and prostate gland may require even more prolonged therapy. The client should be informed that amelioration of clinical signs is not a reliable indicator of successful eradication of UTI, and medication should be administered throughout the recommended treatment interval.

Urine may be cultured immediately before discontinuing therapy to ensure that infection has been eradicated and superinfection has not developed. Bacterial culture should then be performed on urine obtained by cystocentesis 7 to 10 days after completing therapy to detect relapses. Urine should also be cultured approximately 1, 2, 3, 6, and 12 months after terminating therapy to detect reinfections or delayed relapses.

Table 1: Possible Causes of Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections

Prophylactic Therapy

Long-term, low-dose antimicrobial therapy has been used to prevent recurrent infections in patients who continue to develop infection despite appropriate management. Chronic administration of antibiotics has been used commonly in the past, but may predispose to development of antimicrobial resistance and should therefore be used judiciously. The recent escalation in the number and pathogenicity of multi-drug resistant bacteria emphasizes the need for caution and attention to public health concerns when considering prophylactic antibiotic therapy. Before initiating long-term antimicrobial therapy, urine should be sterile. Antimicrobial agents used for long-term therapy include amoxicillin, ampicillin, first generation cephalosporins, trimethoprim-sulfonamide combinations, nitrofurantoin, or others given at one half of their usual daily dosage. The antibiotic should be administered nightly after micturition and before bedtime for at least 6 months. Administration before bedtime (or other extended interval of confinement) assures that the urinary bladder fills with urine containing a high concentration of the antimicrobial agent. During long-term therapy, urine specimens should be collected by cystocentesis for culture approximately once every 4 to 6 weeks. If urine cultures are negative, therapy is continued. However, should bacteriuria recur, the infection should be treated as an episode of acute, uncomplicated UTI. If after 2 weeks of therapy the urine is again sterile, long-term preventive antimicrobial administration may be resumed. At the end of six consecutive months of bacteria-free urine, long-term antimicrobial therapy may be terminated. Most patients that remain uninfected for 6 months usually do not develop additional episodes of infection.

Table 2: Possible explanations for a negative culture despite visible bacteriuria on microscopic exam:

Newsletter

From exam room tips to practice management insights, get trusted veterinary news delivered straight to your inbox—subscribe to dvm360.