Megacolon: the hard facts (Proceedings)

Constipation is defined as the infrequent or difficult evacuation of stool. It is a common problem in cats that may be acute or chronic and does not inherently imply a loss of colonic function. Often the underlying cause is dehydration and is readily managed by supportive hydration, by oral, nutritional or parenteral means.

Definitions

Constipation is defined as the infrequent or difficult evacuation of stool. It is a common problem in cats that may be acute or chronic and does not inherently imply a loss of colonic function. Often the underlying cause is dehydration and is readily managed by supportive hydration, by oral, nutritional or parenteral means. When a cat has intractable constipation that is unresponsive to therapy or cure, this is referred to as obstipation. Obstipation implies permanent loss of function. When obstipation results in dilatation of the colon or hypertrophy of the colon, then the condition is described as megacolon.

Overview

Constipation is more prevalent than we recognize. Clients may perceive firm pellets as being "normal" and report them as such when queried by the veterinary team. If their cat defecates in the garden or if the litter pan is not cleaned on a daily basis, they may be unaware that their cat has excessively dry stool. Cats are presented because of a client's observation of reduced, absent or painful, elimination of hard stool. Cats may pass stool outside the box as well as in it, may posture and attempt to defecate for prolonged periods or may return to the box to try repeatedly to pass stool, unsuccessfully. There may be mucus or blood passed associated with irritative effects of impacted stool, and even, intermittently, diarrhea. Vomition is frequently associated with straining. Inappetence, weight loss, lethargy and dehydration become features of this condition if unresolved. Dilated megacolon is preceded by repeated episodes of recurrent constipation and obstipation. In the cat with hypertrophic megacolon, there may be a known history of trauma resulting in pelvic fracture.

Not only is constipation uncomfortable, it is a sign of cellular water deficit. When a cell is dehydrated and the water intake (from drinking and eating) of the cat is maximized, the kidneys have reclaimed as much water as they are capable of, then colonic contents are the last source of water to try to regulate hydration. Determining the actual character of a cat's feces, while unsavory, is important in assessing their overall condition. Asking the client if there has been a change in stool character may not elicit the information; if a cat has had hard stool for months, even if the client is aware that the stool is pelleted, the question will not produce this information. Asking the client to tell you if the stool is hard pieces, moist logs, semi-formed (cow patties) or "coloured water" will draw out the desired information.

Etiology and pathophysiology

Dilated megacolon is the end-stage condition of idiopathic colonic dysfunction. The resulting disease has diffuse colonic dilatation and hypomotility. Hypertrophic megacolon is a result of pelvic fracture malunion and stenosis of the pelvic canal or another obstructive mechanism including neoplasm, polyp, or foreign body. Colonic impaction is the accumulation of hardened feces in the pelvic colon and is the consequence of constipation, obstipation or megacolon. It does not, in itself, imply loss of function or reversibility of the problem. This distinction is critical in considering treatment plans as well as prognosis.

In humans, there are two recognized forms of megacolon:

1. Congenital aganglionic megacolon (Hirschsprung's Disease): During embryologic development, it is normal for the neural crest cells, which develop into the enteric neuronal plexus (Meissner's submucosal and Auerbach's myenteric) network. Congenital aganglionic megacolon is a disease in which the migration of neural crest cells arrests before reaching the anus resulting in a segment of the distal bowel lacking enteric neuronal coordination. This results in functional obstruction and colonic dilatation proximal to the affected segment. Distension of the colon may reach a diameter of 15-20 cm. As the colon distends, there is hypertrophy of the wall; eventually, if the distension outstrips the hypertrophy, thinning occurs which may result in rupture. Impacted feces may also, at any stage of the disease, cause mucosal inflammation and shallow ulceration.

2. Acquired megacolon is a condition of any age and may be from

a. Chagas' disease, a trypanosomal infection

b. Obstruction by neoplasm or inflammatory stricture

c. Toxic megacolon from ulcerative colitis of Crohn's disease involving the colon

d. Functional psychosomatic illness.

In Chagas' disease, trypanosomes destroy the enteric plexus; in the other three conditions, there is no deficiency of mural ganglia.

In cats with megacolon, congenital hypoganglionosis has only recently been identified in a case report of a single kitten1. Dysautonomia is uncommonly seen in North America, but should consider if concurrent ocular, esophageal, gastric, or lower urinary tract problems are noted2. Dr. Robert Washabau and his co-workers have studied idiopathic feline megacolon extensively and have identified that the underlying problem is characterized by abnormalities in smooth muscle function3-5.

Clinical diagnosis

Constipation, obstipation and megacolon may be seen in cats of any age, breed and gender, however middle aged (mean 5.8 years), male (70%) domestic short-haired (46%) cats appear to be more at risk for megacolon.

Cats are presented because of a client's observation of reduced, absent or painful, elimination of hard stool. Cats may pass stool outside the box as well as in it, may posture and attempt to defecate for prolonged periods or may return to the box to try repeatedly to pass stool, unsuccessfully. There may be mucous or blood passed associated with irritative effects of impacted stool, and even, intermittently, diarrhea. Vomiting is frequently associated with straining. Inappetence, weight loss, lethargy and dehydration become features of this condition if unresolved. Dilated megacolon is preceded by repeated episodes of recurrent constipation and obstipation. In the cat with hypertrophic megacolon, there may be a known history of trauma resulting in pelvic fracture. Impaction and enlargement of the colon is the underlying finding in all cases of megacolon. It may be difficult to differentiate this abnormality from neoplasia, so radiographs will be required.

Cats with dysautonomia will have signs referable to other autonomic defects, such as urinary incontinence, regurgitation, mydriasis, prolapse of the nictating membrane and bradycardia. Digital rectal examination under sedation or anaesthesia should be performed in all cats to rule-out pelvic fracture, malunion, rectal diverticulum, perineal hernia, anorectal stricture, foreign body, neoplasia or polyps. A neurological examination should be performed to detect any neurological causes of constipation, including pelvic nerve trauma, spinal cord injury, or sacral spinal cord deformities of Manx cats.

Serum biochemistries and a complete blood count characteristically are normal, however, these should be performed in order to detect those cats with electrolyte abnormalities (hypokalemia, hypercalcemia, dehydration). A baseline serum T4 should be checked in obstipated kittens suspected of being hypothyroid.

Abdominal radiography should be performed to characterize the mass and verify that it is, indeed, colonic impaction. Radiographs will also help to identify predisposing factors such as pelvic fracture, extra-luminal mass, foreign body, and spinal cord abnormalities. Colonic impaction does not, in itself, imply irreversible, medically irresolvable, megacolon. Barium enemas, or colonoscopy and ultrasound may be additional tools required to help define the problem. CSF evaluation is warranted in cats with neurological involvement.

Therapeutics

Medical management

There are five components to medical management of the cat with recurrent constipation, obstipation or megacolon.

1. Achieve and maintain optimal hydration

2. Remove impacted feces

3. Dietary fiber

4. Laxative therapy

5. Colonic prokinetic agents

1) As long as cellular dehydration is present, the need will exist to resorb water from renal and gastrointestinal systems. Thus, systemic hydration must be addressed. This may be achieved through parenteral fluid therapy, including regular subcutaneous fluids in the home, feeding canned foods, adding water or broth to the food, feeding meat broths, or the use of running water fountains in the home. Addition of fiber to the diet should be avoided until the patient is adequately hydrated.

2) Removal of impacted feces is required to reduce the toxic and inflammatory stress on the bowel wall. Pediatric rectal suppositories may be used to help with mild constipation. They include dioctyl sodium sulfosuccinate (e.g.,Colace™), glycerin or bisacodyl (e.g.,Dulcolax™).

Enemas are another way to soften hardened stool. Solutions that may be used include warm tap water, dioctyl sodium sulfosuccinate (5-10 ml/cat), mineral oil (5-10 ml/cat) or lactulose (5-10 ml/cat). Enemas should be administered slowly through a well- lubricated 10-12 French rubber catheter. Mineral oil and dioctyl sodium sulfosuccinate should not be given together as it promotes mucosal absorption of the mineral oil. Sodium phosphate containing enemas (e.g., Fleet™) are contraindicated because they predispose to life-threatening electrolyte imbalances (hypernatremia, hyperphosphatemia and hypocalcemia) in cats. Hexachlorophene containing soaps should be avoided in enemas because of potential neurotoxicity. Finally, enemas given too rapidly may cause vomiting, pose a risk for colonic perforation and may be passed too rapidly for the fecal mass to be softened by them.

Manual extraction may be required in recalcitrant cases. Infusion of water into the colon, manual massage and reduction of the mass by abdominal palpation and gentle use of sponge forceps to break down the fecal mass may be helpful. Caution must be used to reduce the risk of perforation. Anytime a cat is anaesthetized for manipulations of the colon, an endotracheal tube should be in place, in case the cat vomits.

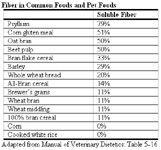

3) Dietary fiber acts as a bulk-forming laxative. The benefits of insoluble (poorly fermentable) fiber, such as from wheat bran and cereal grains, are to improve or normalize colonic motility by distending the colonic lumen, they increase colonic water content, they dilute luminal toxins (such as bile acids, ammonia and ingested toxins) and they increase the rate of passage of ingested materials thereby reducing the exposure of the colonocyte to toxins, while increasing the frequency of defecation.

Soluble (highly fermentable) fibers (oat bran, pectin, beet pulp, vegetable gums, psyllium) are readily digested by bacteria and provide large quantities of short chain fatty acids, which are beneficial in many ways for colonic health, but they are not suitable as laxatives, because they have little ability to increase fecal bulk or dilute luminal toxins.

In nature, most fibers are not strictly insoluble or soluble, but can be considered to have a greater or lesser percentage of soluble fiber. Pectin and guar gum are 100% soluble fiber. Suggested doses are: psyllium (Metamucil™, 1-4 tsp mixed with food PO q12-24h), canned pumpkin (1-4 tbsp mixed with food PO q24h), coarse wheat bran (1-2 tbsp mixed with food PO q24h).

Fiber in Common Foods and Pet Foods

Recently a psyllium-enriched dry extruded diet (Royal Canin Fiber Response) has been studied in France and in Canada6. It was shown to be beneficial in the treatment of cats with recurrent constipation attributed to dilated or hypertrophic megacolon. While some of the 54 cats required fluid therapy and enemas initially, oral laxatives and other medications were discontinued.

4) Besides bulk forming, laxatives may be categorized as emollient, lubricant, hyperosmotic and stimulant, based on their method of action. Emollient laxatives are anionic detergents that increase the miscibility of water and lipid in ingesta, enhancing lipid absorption and impairing water absorption. Dioctyl sodium sulfosuccinate (Colace™, 50 mg PO q24h) and dioctyl calcium sulfosuccinate (Surfax™, 50 mg PO q12-24h) are examples of emollient laxatives that have been used in cats. Dioctyl sodium sulfosuccinate should not be confused with dextran sulphate sodium (DSS), which is actually used as a model for studying irritative colitis.

Lubricant laxatives impede water absorption as well as enabling easier passage of stool. Mineral oil (10-25 ml PO q24h) or petrolatum (hairball remedies, 1-5 ml PO q24h) are best suited to mild cases of constipation. Additionally, mineral oil is better administered by enema rather than orally, because of the risk of aspiration pneumonia. Used chronically, lubricant laxatives may interfere with the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins.

Hyperosmotic laxatives stimulate colonic fluid secretion and propulsive motility. While there are three types (poorly absorbed polysaccharides [lactulose, lactose], magnesium salts [magnesium citrate, magnesium sulfate, magnesium hydroxide] and polyethylene glycols [GoLYTELYTM, Colyte™]), lactulose (0.5 ml/kg PO q8-12h, prn) is the safest and most consistently effective agent in this group. Kristalose is a product consisting of lactulose crystals for reconstitution that cats may accept more readily sprinkled on their food or suspended in water. The magnesium salts are contraindicated in cats with renal insufficiency. Miralax, polyethylene glycol (PG3350) may be used in cats at a dose of 1/8 - 1/4 tsp twice daily in food; polyethylene glycols are contraindicated with functional or mechanical bowel obstruction.

The stimulant laxatives enhance propulsive motility by a variety of actions. One example, which has been used in cats, is bisacodyl (Dulcolax™, 5 mg PO q24h), which acts by stimulating nitric oxide-mediated epithelial call secretion and myenteric neuronal depolarization. Long-term use may result in myenteric neuron damage.

5) Colonic prokinetic agents are a relatively new class of drug, which have the ability to stimulate motility from the esophagus aborally. Older motility agents have been unsuccessful, either because of significant side-effects (bethanechol) or the inability to enhance motility in the distal gastrointestinal tract (metaclopromide, domperidone). Cisapride (Propulsid™, Prepulsid™) belongs to the group of benzamide prokinetic drugs and has been shown, anecdotally, to be beneficial in cases of mild to moderate constipation. Cats with longstanding obstipation or megacolon are not likely to be helped much by cisapride. Published dose recommendations are 2.5 mg PO q8-12h; this author routinely uses 5 mg/cat PO q8-12h without noted side effects. Signs of acute toxicosis in dogs include diarrhea, dyspnea, ptosis, tremors, loss of righting reflex, hypotonia, catalepsy and convulsions.

Cisapride has been withdrawn from the pharmaceutics market because of cardiac toxicity in a small, select group of human patients. Veterinarians may request cisapride from compounding pharmacists.

Newer promotility drugs have not yet received wide use in veterinary medicine. Some suggested doses and comments by Dr. Washabau follow: "Cats treated with prucalopride at a dose of 0.64 mg/kg experience increased defecation within the first hour of administration. Fecal consistency is not altered by prucalopride at this dosage. The therapeutically effective dose for tegaserod in cats is 0.1-0.3 mg/kg PO BID.

Surgical management

Cats with chronic obstipation or megacolon should be considered as candidates for colectomy. Chronic fecal impaction results in mucosal ulceration and inflammation and risk of perforation. Surgery should be done before bowel wall and patient health are compromised and debilitated. Recently, a biofragmentable anastamosis ring was evaluated and found to be an acceptable alternative to traditional suture techniques. Regardless of anastomotic technique, survival outcome after colonic resection is excellent for cats with idiopathic megacolon.

At the time of resection, small intestinal biopsies are advised, as concurrent, underlying disease (e.g. lymphosarcoma, feline infectious peritonitis) may be identified. For cats with pelvic trauma, repair of fractures should be as prompt as possible; lesions older than six months may need to be refractured to allow proper alignment. Dorsal plating of feline iliac fractures may reduce complications associated with pelvic canal narrowing such as constipation and megacolon8. Post-operatively, diarrhea may be present for 4-6 weeks. As anal tone isn't compromised, this does not result in house soiling. The prognosis for recovery is good.

Summary

Regardless of the cause, any cat straining to pass hard stool, is suffering from some degree of dehydration. By addressing and resolving the dehydration, many cats appearing to be obstipated or even to suffer from megacolon, may be found to need more water in their diet. In others, diagnostics should be pursued to rule out alternative diagnoses than idiopathic dilated megacolon. Medical management of true megacolon may be successful for a variable number of years, but eventually, cats may require colectomy. A new psyllium-enriched dry extruded diet is a promising option. As medical treatments become less effective, surgery should be considered earlier, rather than later and the outcome and prognosis is good.

References

Roe KAM, Syme HM, Brooks HW. Congenital large intestinal hypoganglionosis in a domestic shorthair kitten. J Feline Med Surg. May 2010;12(5):418-20.

Novellas R, Simpson KE, Gunn-Moore DA, et al. Imaging findings in 11 cats with feline dysautonomia. J Feline Med Surg. August 2010;12(8):584-91.

Washabau R, Stalis I. Alterations in colonic smooth muscle function in cats with idiopathic megacolon. Am J Vet Res 1996; 57: 580–86.

Washabau RJ, Hasler AH. Constipation, Obstipation and Megacolon. In: August JR (ed), Consultations in Feline Internal Medicine 3, Philadelphia, WB Saunders Co, 1997, p106.

Bertoy RW. Megacolon in the Cat. In: Topics in Feline Surgery. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. July 2002; 32(4): 901-15

Freiche V, Deswarte G, Soulard Y, et al. A Psyllium-Enriched Dry Extruded Diet Improves Recurrent Feline Constipation (Abstract) 20th ECVIM-CA Congress, 2010.

Ryan S, Seim, 3rd H,MacPhail C, et al. Comparison of biofragmentable anastomosis ring and sutured anastomoses for subtotal colectomy in cats with idiopathic megacolon Vet Surg. December 2006;35(8):740-8.

Langley-Hobbs SL, Meeson RL, Hamilton MH, et al. Feline ilial fractures: a prospective study of dorsal plating and comparison with lateral plating. Vet Surg. April 2009;38(3):334-42.