Osteosarcoma: What chemo? When? (Proceedings)

Osteosarcoma is the most common primary bone tumor in the dog (85% of skeletal malignancies). It is estimated to occur in over 8,000 dogs/year in the United States.

Incidence and Risk Factors

Osteosarcoma (OSA) is the most common primary bone tumor in the dog (85% of skeletal malignancies). It is estimated to occur in over 8,000 dogs/year in the United States. OSA has bimodal age incidence peaks at 18-24 months and 7 years and occurs predominately in large to giant breed dogs in the appendicular skeleton at metaphyseal sites, whereas smaller breed dogs generally have their OSA in the axial skeleton. For appendicular OSA, the saying "Away from the elbow and close to the knee" is a good generalization; however, OSA can occur at sites such as distal tibia and others. In addition OSA is seen in the oral cavity (maxilla or mandibular), nasal cavity, ribs, digits and many other bony sites. The etiology of OSA is unknown but thought to be related to traumatic microfractures.

Pathology and Behavior

OSA is a malignant mesenchymal tumor of primitive bone cells. The presence of extracellular matrix production of osteoid helps differentiate OSA from other bone sarcomas such as chondrosarcoma, lymphosarcoma, Hemangiosarcoma, and others. There are multiple histologic sub-classifications (osteoblastic, fibroblastic, chondroblastic, telangiectatic, etc.) for OSA; however, sub-classifications do not presently appear to be prognostic. OSA causes bone lysis, production of bone, or both; pathological fractures can occur. Less than 5% of dogs present with radiographically detectable pulmonary metastasis whereas > 90% have micrometastases at presentation.

History and Clinical Signs

Most dogs with OSA present for lameness and/or swelling at the local site if appendicular in origin. For non-appendicular OSA, the history and clinical signs are dependant on the specific site of origin.

Diagnosis

Local radiographs document soft tissue swelling, bone lysis, production of bone, or a combination of both. The differential diagnosis for OSA includes: Primary or secondary bone tumor, myeloma, lymphoma, and osteomyelitis. The definitive diagnosis of OSA requires bone biopsy. While most biopsies of cancer aim for the periphery of a lesion, bone biopsies should be taken from the center of the lesion and multiple biopsies should be performed. In addition, a full physical examination with close palpation of local lymph nodes (aspirate & examine if enlarged) is also recommended. For additional staging, three view thoracic radiographs are strongly recommended. The utility of additional staging diagnostics such as bone survey radiographs and/or nuclear medicine bone scanning are somewhat controversial. A surgical staging system suggests most OSA are stage IIb (high-grade, extracompartmental and no gross metastasis).

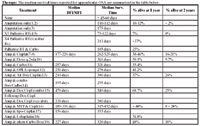

Therapy: The median survival times reported for appendicular OSA are summarized in the table below.

History and Clinical Signs

Prognostic Factors

Better

- No overt metastasis

- tumor necrosis (neoadjuvant chemotherapy only)

- Mandibular location

Worse

- < 5 yr age

- tumor size

- Proximal humerus » 40 kg weight

- ALP

- grade

References

(1) Spodnick GJ, Berg J, Rand WM, Schelling SH, Couto G, Harvey HJ et al. Prognosis for dogs with appendicular osteosarcoma treated by amputation alone: 162 cases (1978-1988). JAVMA 1992; 200:995-999.

(2) Brodey RS, Riser WH. Canine osteosarcoma. A clinicopathologic study of 194 cases. Clin Orthop 1969; 62:54-64.

(3) Mauldin GN, Matus RE, Withrow SJ, Patnaik AK. Canine osteosarcoma. Treatment by amputation versus amputation and adjuvant chemotherapy using doxorubicin and cisplatin. J Vet Intern Med 1988; 2:177-180.

(4) McEntee MC, Page RL, Novotney CA, Thrall DE. Palliative Radiotherapy for Canine Appenicular Osteosarcoma. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 1993; 34:367-370.

(5) Ramirez O, III, Dodge RK, Page RL, Price GS, Hauck ML, LaDue TA et al. Palliative radiotherapy of appendicular osteosarcoma in 95 dogs. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 1999; 40:517-522.

(6) Green EM, Adams WM, Forrest LJ. Four fraction palliative radiotherapy for osteosarcoma in 24 dogs. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2002; 38:445-451.

(7) Straw RC, Withrow SJ, Richter SL, Powers BE, Klein MK, Postorino NC et al. Amputation and cisplatin for treatment of canine osteosarcoma. J Vet Intern Med 1991; 5:205-210.

(8) Kraegel SA, Madewell BR, Simonson E, Gregory CR. Osteogenic sarcoma and cisplatin chemotherapy in dogs: 16 cases (1986-1989). JAVMA 1991; 199(8):1057-1066.

(9) Thompson JP, Fugent MJ. Evaluation of survival times after limb amputation, with and without subsequent administration of cisplatin, for treatment of appendicular osteosarcoma in dogs: 30 cases (1979-1990). JAVMA 1992; 200:531-533.

(10) Berg J, Weinstein MJ, Springfield DS, Rand WM. Results of surgery and doxorubicin chemotherapy in dogs with osteosarcoma. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1995; 206:1555-1560.

(11) Bergman PJ, MacEwen EG, Kurzman ID, Henry CJ, Hammer AS, Knapp DW et al. Amputation and carboplatin for treatment of dogs with osteosarcoma: 48 cases (1991 to 1993). J Vet Intern Med 1996; 10:76-81.

(12) Straw RC, Withrow SJ, Douple EB, Brekke JH, Cooper MF, Schwarz PD et al. Effects of cis-diamminedichloroplatinum II released from D,L-polylactic acid implanted adjacent to cortical allografts in dogs. J Orthop Res 1994; 12:871-877.

(13) Mauldin GN, Matus RE, Withrow SJ, Patnaik AK. Canine osteosarcoma. Treatment by amputation versus amputation and adjuvant chemotherapy using doxorubicin and cisplatin. J Vet Intern Med 1988; 2:177-180.

(14) Bailey D, Erb H, Williams L, Ruslander D, Hauck M. Carboplatin and doxorubicin combination chemotherapy for the treatment of appendicular osteosarcoma in the dog. J Vet Intern Med 2003; 17:199-205.

(15) Chun R, Kurzman ID, Couto CG, Klausner J, Henry C, MacEwen EG. Cisplatin and doxorubicin combination chemotherapy for the treatment of canine osteosarcoma: a pilot study. J Vet Intern Med 2000; 14:495-498.

(16) Kurzman ID, MacEwen EG, Rosenthal RC, Fox LE, Keller ET, Helfand SC et al. Adjuvant therapy for osteosarcoma in dogs: results of randomized clinical trials using combined liposome-encapsulated muramyl tripeptide and cisplatin. Clin Cancer Res 1995; 1:1595-1601.

(17) Vail DM, Kurzman ID, Glawe PC, O'Brien MG, Chun R, Garrett LD et al. STEALTH liposome-encapsulated cisplatin (SPI-77) versus carboplatin as adjuvant therapy for spontaneously arising osteosarcoma (OSA) in the dog: a randomized multicenter clinical trial. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2002; 50:131-136.

(18) Kirpensteijn J, Teske E, Kik M, Klenner T, Rutteman GR. Lobaplatin as an adjuvant chemotherapy to surgery in canine appendicular osteosarcoma: a phase II evaluation. Anticancer Res 2002; 22:2765-2770.

(19) Kent MS, Strom A, London CA, Seguin B. Alternating carboplatin and doxorubicin as adjunctive chemotherapy to amputation or limb-sparing surgery in the treatment of appendicular osteosarcoma in dogs. J Vet Intern Med 2004; 18:540-544.

(20) Ehrhart N, Dernell WS, Hoffmann WE, Weigel RM, Powers BE, Withrow SJ. Prognostic importance of alkaline phosphatase activity in serum from dogs with appendicular osteosarcoma: 75 cases (1990-1996). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1998; 213:1002-1006.

(21) Garzotto CK, Berg J, Hoffmann WE, Rand WM. Prognostic significance of serum alkalie phosphatase activity in canine appendicular osteosarcoma. J Vet Intern Med 2000; 14:587-592.

(22) Kirpensteijn J, Kik M, Rutteman GR, Teske E. Prognostic significance of a new histologic grading system for canine osteosarcoma. Vet Pathol 2002; 39:240-246.

Newsletter

From exam room tips to practice management insights, get trusted veterinary news delivered straight to your inbox—subscribe to dvm360.