Periodontal disease in horses: What causes it—and how to fix it

Research is limited in this area of equine veterinary care, but one practitioner has an approach that works.

Periodontal disease is the leading cause of tooth loss in horses, with a prevalence of 35% to 85% in various equine populations. Severe cases can be recognized on routine physical exam if facial swelling, draining tracts or sinusitis is present. With equine periodontal disease, gingival disease is also usually present in the form of hyperplasia, recession and inflammation.1

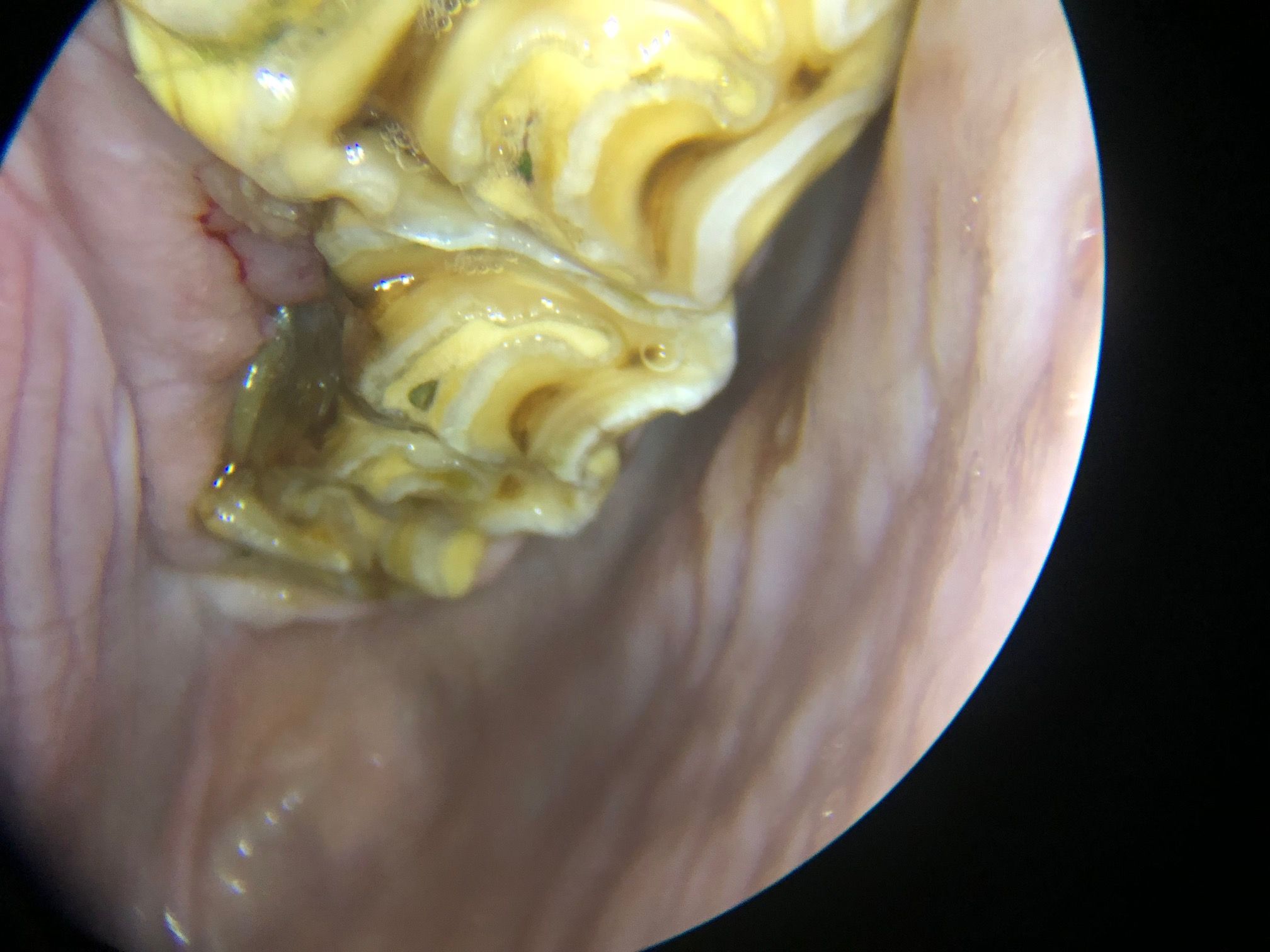

Matt Evans, DVM, of Austin Equine in Driftwood, Texas, believes that most periodontal disease in horses is secondary to food stasis, or organic debris lodged between two teeth against the periodontia (Figure 1). But discovering the condition is only the beginning of the diagnostic process.

Figure 1. A fracture and subsequent periodontal disease in tooth 211. The problem, says Dr. Evans, is always under the organic matter. (All images courtesy of Dr. Matt Evans)

“Is food or debris lodging between teeth the primary issue, or is it secondary to a fractured tooth with some part of the tooth missing?” Dr. Evans asks. “Or do we have a malocclusion, like a rotated or a tilted tooth, that’s allowing the organic debris packing and subsequent disease?”

The earlier the diagnosis, the better the outcome

Dr. Evans notes that the key to diagnosing periodontal disease is a well-sedated horse so you can perform a thorough examination and remove any debris. “When one finds food packing between teeth, that’s where periodontal disease is going to be lying underneath,” he says. “It’s also interesting to try to figure out the primary cause and see if it’s something that can be addressed.”

To identify periodontal disease, the veterinarian must sedate the horse to facilitate a full oral exam. Periodontal disease of the cheek teeth will not be seen on an unsedated exam.

“With horses whose teeth line up normally—when they don’t have any malocclusions or fractured teeth—they’re basically ‘brushing their teeth’ all the time with the roughage they consume,” Dr. Evans says. “It’s not the same mechanism as periodontal disease in humans. In horses, it’s more about gaps being created, which then become impacted with food debris.”

There is evidence that horses nourished predominantly on green grass pastures have significantly less dental disease of all kinds, including periodontal disease, than those fed dry feed, hay and dry forage.2 This matches Dr. Evans’ experience.

“In my practice, most horses I see are fed dry roughages—coastal hay, alfalfa hay and the like—and are more prone to periodontal disease,” he says. “We don’t see many horses that are eating primarily on green grass pasture.”

When trying to determine the best treatment option for periodontal disease, equine practitioners don’t have much research to draw on. Dixon and colleagues in 2014 concluded that diastema widening is an effective treatment for severe disease, but it’s potentially invasive.3

So, Dr. Evans focuses on the basics. “When I examine cases of periodontal disease and attachment loss, I’m trying to quantify the extent of the disease with measurements and decide which treatment option to pursue—pack the area with antibiotics and/or polyvinyl siloxane or only debride the pocket,” he says.

Tools needed to diagnose periodontal disease include a headlamp or dental speculum light, mirror and possibly an oral endoscope. Plus, “you have to have instruments for removing debris (wound lavage, alligator forceps) and be willing to sedate a patient adequately,” states Dr. Evans. “Sedation is necessary as it provides a comfort level in evaluating malocclusions and potential tooth fractures, and for the pain involved in cleaning out impacted food debris.”

Once he’s identified an area with significant food stasis, removed organic debris and evaluated the area using a mirror or oral scope, Dr. Evans tries to quantify the situation as best as possible. He uses a periodontal probe marked with 5-mm increments (Figure 2) to measure periodontal pocket depth compared with surrounding gingiva as well as lesion diameter. “Depth times diameter assists in deciding how much potential attachment loss the horse has,” he says.

Figure 2: Periodontal probe with 5-mm graduated measurements used to assess depth compared with the surrounding gingiva.

To assess periodontal disease in horses, three types of indices are necessary: tooth mobility, gingivitis and periodontal disease.1

Tooth mobility index:

- Mild normal

- Any discernable movement greater than normal

- Moderate movement up to 3 mm

- Severe movement greater than 3 mm in any direction

Gingivitis index:

- Normal gingiva

- Mild inflammation: slight edema, slight color changes, no bleeding on probing

- Moderate inflammation: redness, edema and glazing, bleeding on probing

- Severe edema

Periodontal disease index:

- Normal

- Gingivitis, no bone loss, probing depth less than 5 mm

- Early periodontal disease: less than 25% attachment loss

- Moderate periodontal disease: 25% to 50% attachment loss

- Advanced periodontal disease: greater than 50% attachment loss

Assessing horses presenting with periodontal disease

Many horses with oral disease present with no clinical complaints and the condition is found on routine dental examination while the horse is under sedation. “Sometimes it’s hard to convince a client to proceed with treatment if you see periodontal disease but the horse is not showing any signs,” Dr. Evans explains.

If the horse comes in with halitosis, quidding (dropping food or eating slowly) or weight loss—the “big three” chief complaints—it’s a different story, Dr. Evans states. “Upon mouth exam, you then find periodontal disease, and the owners in those cases are much more likely to pursue radiographs and possible therapies,” he says.

In most cases, the veterinarian needs radiographs to quantify the bone loss and to assign a periodontal disease grade.

“When I’m cleaning out periodontal pockets, I use a wound 'lavage,'” states Dr. Evans. “I set up a pressure bag with sodium saline or sodium saline with dilute chlorhexidine, with an 18-ga needle with the end broken off. The goal is to try to stay under 19 psi.”

Some veterinarians use a Waterpik or similar high-pressure human instrument when cleaning out periodontal pockets. But “there’s a concern that if one uses too much pressure (such as with a Waterpik), you’re driving the debris and bacteria deeper into the wound,” Dr. Evans says. “When I’m cleaning out a periodontal pocket, I assume the periodontal disease is laying over the gingiva. The gingiva is not just red and inflamed but also has erosive lesions with granulation tissue. I’m always worried about putting too much pressure in there and driving things deeper into the inflammatory tissue, so I use the ‘lavage bag’ to clean them out.”

Another option, as mentioned previously, is diastema widening as described by Dixon.3 “If one burrs away a part of the teeth affected by a diastema, you can open the area so food will move through freely,” Dr. Evans says. “With horses whose teeth have a very small pocket, you might decide to clean it out and put something synthetic, such as polyvinyl siloxane or methacrylate, into that pocket to try to close the gap up and keep food from being re-impacted into it.”

In terms of understanding, identifying, diagnosing and treating periodontal disease in horses, Dr. Evans says “we’re doing a better job diagnosing and identifying periodontal disease and have a better idea when we shoot radiographs. We don’t know exactly what therapies we should be reaching for, though we’ll begin to see more research coming out in the next four to five years that will give us a more definitive method to choose appropriate therapies. I think we’re headed that way.”

Case of older horse with periodontal disease

“I had a geriatric (23-year-old) Arabian mare that was experiencing weight loss, halitosis and quidding,” Dr. Evans recalls. “She had a major diastema between two of her two distal maxillary cheek teeth (206 and 207, Figure 3). I was able to clean the pocket out and, using my periodontal probe, I realized there was a very large cheek teeth pocket there that was greater than 1 cm deep, with a 5-to 7-mm diameter across its palatal aspect. As she presented with considerable complaints, I was able to find that area, which I identified as significant periodontal disease. I was able to recommend radiographs. None of those teeth had significant mobility, but I was able to identify bone loss surrounding tooth 206. I recommended extraction, which the owner accepted. The clinical signs resolved immediately after the extraction.”

Figure 3. Diastema and subsequent periodontal disease between two maxillary cheek teeth.

“The knowledge that I needed to remove the impacted feed to quantify the disease process led me to take radiographs,” Dr. Evans noted. “Reading the radiographs allowed me to identify the bone loss. Prior to identifying her periodontal disease, I could have worked a long time just floating to deter malocclusions in different places. Finding and cluing in on her periodontal disease allowed me to help that mare out.”

Summary

Periodontal disease is the leading cause of tooth loss in horses, especially in older horses, and it is primarily caused by food debris impacted between cheek teeth. For the most part, information about how to diagnose, treat and help horses heal with periodontal disease is available to equine practitioners. According to Dr. Evans, there is still much more research and learning that needs to be done, and there is a lack of significant evidence-based literature, but new papers should be coming in the future.

References

1. Evans M. How to diagnose periodontal disease, in Proc 64th Ann Conv AAEP 2018:39.

2. Klugh D. A review of equine periodontal disease, in Proc 52nd Ann Conv AAEP 2006:551.

3. Dixon PM, Ceen S, Barnett T, et al. A long-term study on the clinical effects of mechanical widening of cheek teeth diastemata for treatment of periodontitis in 202 horses (2008-2011). Equine Vet J 2014;46(1):76.

Suggested reading

• Klugh D. Equine periodontal disease. Clin Tech Equine Practice 2005;4:135.

• Stock S. Periodontal parameters in the normal and pathologic equine tooth, in Proc World Equine Dent Congr 1997:92.

Ed Kane, PhD, is a researcher and consultant in animal nutrition. He is an author and editor on nutrition, physiology and veterinary medicine with a background in horses, pets and livestock.

Newsletter

From exam room tips to practice management insights, get trusted veterinary news delivered straight to your inbox—subscribe to dvm360.