The perplexing pancreas: Pathophysiology of pancreatic disease (Proceedings)

Pancreatitis, either acute or chronic, is a significant clinical problem in both dogs and cats.

Pancreatitis, either acute or chronic, is a significant clinical problem in both dogs and cats. It can be a difficult disease to diagnose initially and subsequently characterize adequately. Ironically, with the advent of the SNAP PLI test, it may soon become a disease that is over-diagnosed; the clinical presentation and laboratory changes are similar to a number of gastrointestinal diseases and ending the diagnostic work-up with a positive SNAP PLI result may lead to the potentially erroneous conclusion that the only, or even the most important disease process in a particular patient is an inflammation of the pancreas.

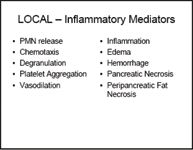

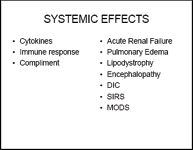

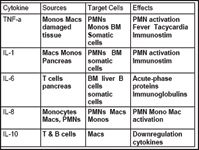

Pancreatic enzymes are normally inactive "zymogens" until released into the lumen of the GI tract where specific enzymes convert these zymogens into powerful digestive enzymes. Premature activation, or the breakdown of the normal protective packaging within lysosomes can result in local, autodigestion of surrounding cells and tissue. This results in acute, local inflammation, the "itis" of acute pancreatitis. The body is equipped with a variety of protective mechanisms and molecules designed to deal with these inappropriately activated enzymes, but if those mechanisms fail there is a rapid amplification of local enzymes as well as systemic mediators - local acute pancreatitis rapidly progresses to life-threatening systemic disease. Critical care specialists have coined a variety of acronyms to describe this systemic insult – SIRS, MODS, ARDS, DIC – that are beyond the scope of this review. Suffice it to say, none of them sound good, and no organ, tissue or system is safe. Local complications can include the formation of a pancreatic pseudocyst, abscess, necrosis and infection, and fat saponification. These patients are at risk for the development of coagulopathies and thromboembolism, suppurative cholangiohepatitis, extrahepatic biliary obstruction, acute renal failure, peritonitis, as well as significant respiratory, cardiac, and neurologic abnormalities. In humans, chronic pancreatitis frequently results in diabetes mellitus or exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, explaining why insulin and pancreatic enzymes are listed as treatments for this disease in that species.

The clinical presentation of pancreatitis appears to be somewhat different in dogs and cats. Dogs are more "classic" with vomiting and abdominal pain being prominent complaints, whereas cats are more subtle (or more difficult to evaluate) and simply stop eating and get lethargic. Dogs may become febrile whereas cats may become hypothermic. Both species may end up collapsed and in shock. Chronic, "smoldering", or recurrent pancreatitis can be even more of a clinically challenging diagnosis with signs that are vague and intermittent.

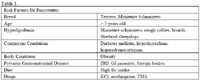

Table 1. Risk Factors for Pancreatitis

Although a minimum database (CBC, biochemical profile, urinalysis) is important in the diagnostic work-up of any patient presenting for gastrointestinal signs, none of the potential abnormalities are specific for pancreatitis, including elevations in serum amylase or lipase. One study did show that a low ionized calcium is a poor prognostic indicator, and a clear understanding of electrolyte and acid-base abnormalities is important for planning supportive care. The blood test that currently appears to be the most sensitive and specific for pancreatic inflammation is the species-specific pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity, or PLI. As with any test, it is important to remember what a positive result actually represents – in this case, an abnormal release of pancreas-specific enzymes into circulation. A positive PLI is consistent with the presence of some degree of pancreatic inflammation, making it very likely that the pancreas is, to some degree, responsible for the clinical presentation. A positive test result does not mean the pancreas is the sole source, the primary source, or even necessarily the most important source of the patient's problems.

Imaging studies are an important part of the diagnostic work-up in cases of GI disease. There are a number of reports with an even greater number of claims regarding the sensitivity and/or specificity of abdominal radiographs and ultrasound. The take-home message appears to be that the skill of the person interpreting the results is crucial and a "negative" result should not take pancreatitis off the list of differentials if clinical acumen put it there in the first place.

At Colorado State University we completed a retrospective study that highlighted the important role that laparoscopic visualization and biopsy of the pancreas can play in the diagnosis of pancreatic disease. Laparoscopy is a minimally invasive and diagnostically powerful technique that requires a relatively modest investment of time, money and training before it is a very viable practice tool.

Table 2. Treatment Considerations and Controversies

Notes regarding feline pancreatitis

Although we are taught to do everything possible to give our patients one and only one disease, the cat appears to be the exception to this "rule". Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) is the ultimate example, where studies show that the vast majority of cats that present as DKA have a concurrent disease; failure to appreciate or address this is undoubtedly a big part of the reason so many DKA cats become "repeat offenders". It may be that feline pancreatitis is a similar sort of disorder – and in fact, studies also show that one of the more common concurrent disorders to show up in a DKA cat is pancreatitis! The constellation of concurrent disorders in the cat with pancreatitis is seen often enough to warrant it's own name – Triaditis. Triaditis is defined as concurrent inflammation of the pancreas, liver, and small intestine. The anatomical proximity of these 3 organs (much of the pancreas is tightly adhered to the duodenum by mesentery and both are in contact with several liver lobes) and the communal "plumbing" (common bile duct joining the pancreatic duct to empty into the duodenum) makes it very plausible that each would "feel the other's pain".

As with the dog, we are rarely able to identify an underlying cause for pancreatitis in feline patients.

Table 3. Potential Causes and Risk Factors for Feline Pancreatitis

Mention has already been made of the subtle clinical presentation in felines and the rarity of the classic canine case (vomiting, abdominal pain, and fever are rare in cats). Lethargy and anorexia describe 90% of the cats brought to a veterinary hospital and pancreatitis now has to be on the list of rule-outs for that patient.

As with the dog, changes in the minimum database are nonspecific, although attention should be paid to those values that suggest involvement of other organ systems (e.g. elevated total bilirubin and liver enzymes). Similar strengths and cautions exist with the interpretation of diagnostic imaging in the cat as were discussed for the dog.

Hydration, pain management, and nutritional support along with any number of additional treatments (Table 2) can be utilized where appropriate, keeping in mind that even more so than the dog, concurrent disorders need to be addressed therapeutically. Anti-inflammatory corticosteroids can be used if appropriate for concurrent disorders, and are otherwise being incorporated more frequently in cats with chronic recurrent pancreatitis.