Proteinuria: What is it and what do I do about it? (Proceedings)

Protein in the urine, particularly when it is of renal origin, can be an indicator of renal damage, and has been found to be associated with progression of renal disease. There are several reasons that protein can enter the urine, through a damaged glomerulus, through lack of reuptake by tubular epithelial cells, and through exudation into the tubular lumen.

Protein in the urine, particularly when it is of renal origin, can be an indicator of renal damage, and has been found to be associated with progression of renal disease. There are several reasons that protein can enter the urine, through a damaged glomerulus, through lack of reuptake by tubular epithelial cells, and through exudation into the tubular lumen. In addition, protein can enter the urine during the collection and storage phase from hemorrhage or exudation in the ureters, bladder, urethra, prostate, or genital tract.

Proteinuria can be classified as pre-renal, renal, or post-renal.

Pre-renal: hemoglobin, myoglobin, immunoglobulin light chains (BJ proteins)

Cause: Strenuous exercise, heat stress, seizures, fever, hemolysis, neoplasia, etc. Indicative of underlying condition and may require additional evaluation

Renal: Indicates pathologic lesions of the kidneys. Can be further classified as glomerular, tubular, or interstitial.

Glomerular: lesions to the glomerular endothelium, basement membrane, or epithelium with damage to permselective function

Tubular: lesions that affect the ability of the proximal tubule to reabsorb small proteins that are able to pass through a normal glomerular barrier

Interstitial: secondary to inflammatory lesions of the interstitum that allow protein to exude into the renal tubules

Post-renal:

Collection method artifact (blood, discharge from the genital tract), hemorrhage or exudative process from the lower urinary tract (ureters, bladder, urethra, prostate, etc.). Important: studies show that urine must have gross change in color before hematuria can lead to detectable proteinuria and that pyuria must also be significant before it affects the protein on a dipstrip. The Heska ERD test will likely pick up changes earlier than dipstrips in these conditions.

For the purpose of this discussion, we will focus on renal causes of proteinuria, but it is important for the clinician to understand and rule out the non-renal sources in order to avoid misdiagnoses.

Structure and Function of the Glomerulus:

MD: macula densa, EA: efferent arteriole, AA: afferent arteriole, B: Bowman's capsule, M: mesangial cell, EN: endothelial cell, BS: Bowman's space, BM: basement membrane, EP: epithelial cell, F: foot processes, PT: proximal tubular cells, G: granular cells, N: sympathetic nerve terminals

Three filtration layers within the glomerulus:

• Fenestrated endothelium

• Glomerular basement membrane

• Visceral epithelial cells

Filtration primarily by size (< 60,000 daltons) and charge (positively charged particles move more easily across than negatively charged particles). These layers provide normal permselectivity which prevents large protein molecules from passing through the glomerulus into the urine. When protein is lost into the urine, the proximal tubule cells usually remove it. However, these mechanisms can be easily overwhelmed and this leads to large amounts of protein accumulation in the tubular epithelial cells and in the tubular lumen. This leads In turn to progressive tubular damage and renal disease. This is one of the major theories as to why the degree of on-going proteinuria appears to relate to the rate of renal disease progression.

Damage to the glomerulus and the subsequent breakdown in protein barrier can occur through amyloidosis or immune-complex deposition and damage to the glomerulus (due to chronic systemic inflammation or neoplasia). Proteinuria can also occur in patients with hypertension which increases the intraglomerular pressure and damages the epithelium and basement membrane, allowing protein to pass through.

In patients with chronic renal disease, proteinuria can exist from multiple sources including glomerular damage, hypertension, proximal tubular injury, and exudative lesions secondary to interstitial nephritis and pyelonephritis.Proteinuria has been shown to be an indicator of progressive renal disease. For this reason it is included as a sub-categorization (along with hypertension) in the International Renal Interest Group (IRIS) staging system.

IRIS Stages of Chronic Renal Disease:

Testing options:

Protein in the urine must be interpreted in light of two things:

Specific Gravity. Even trace protein in a dilute urine sample (< 1.020) may be significant.

Urine Sediment Evaluation. The presence of casts, red blood cells, white blood cells, bacteria, or epithelial cells may give the clinician a clue to the source of the proteinuria. Proteinuria in the face of an inactive sediment increases suspicion for underlying renal and particularly glomerular disease.

**Some animals may have day to day variations in mild proteinuria due to exercise, heat stress, or physical stress, so it is important to confirm the persistence of proteinuria with a few weeks between tests.

Dipstrip (mostly albumin):

Normal urine with a high specific gravity (> 1.050) can often show trace or 1+ protein on dipstrips. Highly alkaline urine can lead to false positives, highly acidic urine can lead to false negatives. Can be negative in patients with significant proteinuria if the urine is very dilute. Patients with a positive protein level on dipstrip should have a urine sediment evaluated. If inactive, a UPC is indicated.

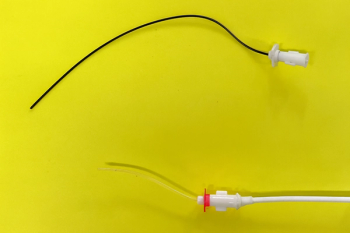

Microalbuminuria (Heska ERD®) test:

Normal < 1 mg/dl (cat and dog), test is designed to detect levels of 1-30 mg/dl of albumin. The presence of microalbuminuria may be an indicator of early renal disease but has also been associated with other conditions such as neoplasia, systemic inflammatory disease, and heartworm disease which can lead to glomerular injury through immune complex deposition. May be a good screening test for patients with possible hereditary protein-losing nephropathies (Soft-Coated Wheaton Terriers), risk of renal disease (patients with diabetes mellitus, thyroid disease, or hypertension), and geriatric cats and dogs. If abnormal, follow-up with a UPC to further quantify magnitude of proteinuria.

Urine Protein : Creatinine ratio (UPC):

Normal < 0.4 (cat and dog), allows for correlation of protein content with the concentration of the urine. Pink or red urine can lead to false elevation, as can pyuria (> 3 WBC/hpf). The degree of proteinuria is only very loosely correlated with the type of renal disease and cannot be used to differentiate glomerular disease from amyloidosis. UPC is generally performed if a patient has an abnormal amount of protein in the urine on dipstrip or has an elevated microalbuminuria test.

Treatment

It is important to remember that any trafficking of protein across the glomerulus leads to further damage and inflammation in the nephron and will cause further progression of renal lesions. For this reason it is important to identify and treat any underlying disease process that may be contributing to the proteinuria. In the event that it is not possible to identify or address an underlying problem, additional measures may be taken to reduce the amount of protein crossing the glomerulus. Angiotensin Converting Enzyme inhibitors (ACEis) will cause mild vasodilation of the efferent arteriole in the nephron, thus acting as a "pop off valve" and reducing pressure in the glomerulus. This is especially important in patients with hypertension or underlying chronic renal disease. Low protein diets may be of benefit in patients with chronic renal disease. The addition of omega-3 fatty acids to the diet may modulate inflammatory mediators and reduce inflammation.

So I performed a UPC and it is elevated, now what?

First, rule out non-renal causes of proteinuria (UTI, bloody urine, prostatitis). This may involve performing a urine culture to rule out bacterial infection. If the patient is being given glucocorticoids this may also increase protein loss in the urine.

Measure blood pressure. As many as 88% of hypertensive dogs can have significant proteinuria (UPC > 1.0) and the same is assumed for cats. If hypertensive look for underlying causes (renal disease, endocrine disease). Be sure to measure with an accurately sized cuff (width is 30-40% of circumference of measured body part).

Evaluate renal function. Determine if renal disease is present by evaluating BUN, creatinine, and urine specific gravity along with hydration status and urine sediment findings. Evaluation may also include imaging of the kidneys and urinary tract.

Look for underlying inflammatory processes including but not limited to pancreatitis, heartworm infection, tick-borne disease, chronic inflammatory disease, and neoplasia.

If unable to rule out other causes, consider glomerular disease or amyloidosis. Renal biopsy is the only definitive way to differentiate these two conditions.

Consider placing the patient on an ACE inhibitor to reduce proteinuria, particularly if unable to identify or treat underlying disease

Place patient on a high quality, low-protein diet and consider supplementing with omega-3 fatty acids to reduce inflammation

References

Bacic A, Kogika MM, Barbaro KC et al. Evaluation of albuminuria and its relationship with blood pressure in dogs with chronic kidney disease. Veterinary Clinical Pathology. (2010) 39(2): 203-209.

Chew DJ, DiBartola SP, Schenck PA. Canine and Feline Nephrology and Urology, 2nd ed. Elsevier, St. Louis, MO, 2010.

Lees GE, Brown SA, Elliot J, Grauer GF, Vaden SL. Assessment and management of proteinuria in dogs and cats: 2004 ACVIM forum consensus statement (Small animal). Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine. (2005) 19:377-385.

Vaden SL, Pressler BM, Lappin MR, Jensen WA. Effects of urinary tract inflammation and sample blood contamination on urine albumin and total protein cncentrations in canine urine samples. Veterinary Clinical Pathology. (2004) 33(1):14-9.

Newsletter

From exam room tips to practice management insights, get trusted veterinary news delivered straight to your inbox—subscribe to dvm360.