Quantitative urolith analysis: A standard of practice?

A quarter-century ago, analysis of uroliths removed (usually by surgery) was optional. In fact, rather than have the stones analyzed, some veterinary practitioners gave them to their clients as a topic of conversation. What about today? Is it an acceptable standard of practice to give stones retrieved from the urinary tract to owners without knowing their composition? What would be your response to a physician who gave you stones retrieved from your urinary tract? Believe it or not, we have received uroliths for analysis formed by our veterinary colleagues that were given to them by a physician. Of course, we did not perform the requested analysis because we did not want to cross the line of practicing medicine without a license. Instead, we sent them to a laboratory licensed to provide that service.

A quarter-century ago, analysis of uroliths removed (usually by surgery) was optional. In fact, rather than have the stones analyzed, some veterinary practitioners gave them to their clients as a topic of conversation. What about today? Is it an acceptable standard of practice to give stones retrieved from the urinary tract to owners without knowing their composition? What would be your response to a physician who gave you stones retrieved from your urinary tract? Believe it or not, we have received uroliths for analysis formed by our veterinary colleagues that were given to them by a physician. Of course, we did not perform the requested analysis because we did not want to cross the line of practicing medicine without a license. Instead, we sent them to a laboratory licensed to provide that service.

Carl A. Osborne

The question that we pose to you is whether making a choice not to request quantitative analysis of uroliths is ethical. Should failure to request quantitative urolith analysis be considered negligence?

Jody P. Lulich

Recall that negligence may be defined as the act of doing (or not doing) something that a person of ordinary prudence would or would not have done in similar circumstances. Negligence implies that a veterinarian did not follow a reasonable standard of care. The standard applies not only to what you do (commission), but also to what you don't do (omission).

The law says that reasonable practitioners, not the most highly skilled professionals, set the standard of care. If an error occurs despite the exercise of due care, negligence is not an issue. In this context, should failure to request quantitative urolith analysis be considered negligence?

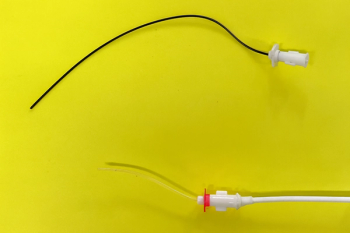

Figure 1: Fragments of a mixture of ammonium urate and struvite that formed around a catheter. (Photo: courtesy of Dr. Carl A. Osborne)

What are uroliths?

Uroliths (also known as calculi) are aggregates of mineral and/or non-mineral substances in the urinary tract. They may vary in size and number, and may form in one or more locations within the urinary tract when urine becomes oversaturated with crystallogenic substances. Uroliths may be composed of one or more biogenic minerals, including magnesium ammonium phosphate (struvite), calcium phosphate (calcium apatite), calcium oxalate monohydrate (Whewellite), calcium oxalate dihydrate (Weddellite), uric acid or salts of uric acid (e.g., ammonium, sodium and calcium urate), silica, cystine and/or xanthine. Also, they may be partly or completely composed of drugs or drug metabolites. If foreign substances (such as suture material, hair or plant material) are present within the lumen of the urinary tract, they often become the nidus for urolith formation (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 2: Calcium oxalate monohydrate that formed around suture material.

Why should uroliths be analyzed?

At our current level of understanding, medical treatment and prevention of the causes underlying urolithiasis are dependent on knowledge of the composition and structure of the entire stone. Minerals in uroliths may be deposited in distinct layers or they may be admixed throughout the stone(s). Although one mineral type usually predominates, the composition of uroliths is frequently mixed (for example, 90 percent struvite and 10 percent calcium phosphate). The center (nidus) may be composed of one mineral type (such as calcium oxalate), whereas outer layers may be composed of one (such as struvite) or more different mineral types (Figures 3 and 4). Therefore, all uroliths retrieved from a patient should be submitted for quantitative analysis. This is a standard of practice in our profession.

Figure 3: Cross-section of a feline compound urocystolith composed of a nidus of urate and a shell of struvite.

In addition to quantitative analysis, non-surgical methods of urolith management in cats and dogs have become a standard of practice in the veterinary profession. Choice of treatment or prevention based on results of quantitative mineral analysis of stones consistently provides the most favorable outcome.

Figure 4: Cross-section of a laminated urolith composed of a nidus of amorphous silica and a shell of struvite.

How can uroliths be retrieved for analysis?

Until the early 1980s, surgery was considered the only practical method of retrieving uroliths. However, we have devised several different means to move and remove uroliths from the patient. Small urocystoliths can be retrieved from the urinary bladder by "jiggling" the stones in the bladder while urine or saline and small stones are aspirated through a urinary catheter into a syringe.

Uroliths also may be removed from the bladder by voiding urohydropropulsion. Urocystoliths spontaneously voided through the urethral lumen to the exterior may be harvested with the aid of a small aquarium fishnet placed in the patient's urine stream.

Stone baskets also may be used to remove uroliths.

Additional information about these techniques is available at our Web site,

How should uroliths be submitted for analysis?

Methods by which uroliths are submitted for analysis may have a substantial impact on the quality of the analysis.

Table 1 offers a list of dos and don'ts of urolith submission.

What methods of analysis are recommended?

Two general methods of urolith analysis may be considered: qualitative analysis and quantitative analysis. Qualitative analysis usually is performed using spot chemical tests to identify chemical radicals and ions. This archaic method has been virtually abandoned as unreliable. Because most qualitative techniques require pulverizing the stone, layers of different minerals frequently identified by quantitative methods of analysis typically cannot be identified. Also, these tests were not designed to identify many crystalline components of uroliths, including amorphous silica and silica salts, drugs and drug metabolites (e.g., sulfadiazine and allopurinol), newberyite, boberyite, uric acid and its salts and xanthine.

Figure 5: Calcium oxalate monohydrate under 450X magnification.

They are insensitive to detection of calcium and salts of calcium. Because qualitative tests for biogenic minerals are insensitive and lack specificity, they should not be used.

Several physical methods of urolith analysis allow detection and quantification of minerals present in stone(s). These methods include optical crystallography, infrared spectroscopy, X-ray diffraction, energy dispersive techniques and others.

Optical crystallography is based on use of a polarizing microscope to identify crystalline components of uroliths (Figure 5). Representative sections of the stone are identified with the aid of a dissecting microscope.

These samples (or crystal grains, as they are sometimes called) are then viewed with a polarizing scope. Optical properties, such as refractive index and birefringence then are recorded and compared with known standards to determine the mineral type(s).

Infrared spectroscopy is based on the observation that, when infrared waves encounter a sample, some are absorbed by the sample (absorbance) and some pass through the sample (transmission). The resulting spectrum is a molecular fingerprint of the sample (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Infrared spectroscopy.

Because no two unique molecular structures produce the same infrared spectrum, these spectra can be compared to known reference spectra for identification.

Table 1 Dos and don'ts of urolith submission for quantitative urolith analysis

This procedure is useful in identifying unknown materials, determining the quality and consistency of samples and quantifying the amounts of different calculogenic substances within the sample.

Unfortunately, some laboratories persist in performing qualitative analysis. In our view, qualitative analysis does not meet a current standard of practice in the United States.

All laboratories do not report the results obtained by quantitative analysis in the same fashion. Regardless of the method of analysis, the location(s) of minerals within the urolith should be further specified (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Structure of a urolith.

Layers that are grossly visible by examination of cross-sections of stones may or may not contain different types of minerals (Figures 3 and 4).

Formation of so-called metabolic uroliths (e.g., calcium oxalate) followed by formation of infection-induced magnesium ammonium phosphate (e.g., infection-induced struvite) may result in distinct laminations detected by survey radiography or by examination of the cut surface of the stone.

Table 2 Minnesota Urolith Center quantitative urolith analysis form

If significant hemorrhage occurs intermittently, it may affect the appearance of layers on the cut surface without a corresponding change in the mineral composition of the urolith.

We acknowledge the financial support of Hill's Pet Nutrition in providing an educational grant to the Minnesota Urolith Center and extend thanks to our veterinary colleagues for their financial support and confidence in the center.

Carl A. Osborne, DVM, PhD, Dipl. ACVIM

Dr. Osborne, a diplomate of the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine, is professor of medicine in the Department of Small Animal Clinical Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Minnesota.

Jody P. Lulich, DVM, PhD, Dipl. ACVIM

Dr. Lulich, a diplomate of the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine, is a professor in the Department of Small Animal Clinical Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Minnesota.

Newsletter

From exam room tips to practice management insights, get trusted veterinary news delivered straight to your inbox—subscribe to dvm360.