Treatment of refractory urinary incontinence (Proceedings)

Diagnosis and management of the majority of cases are routine; however, treatment of refractory urinary incontinence cases are frustrating for both the veterinarian and owner. The diagnostic approach to dogs with refractory urinary incontinence should include a thorough history (drugs, age of onset, and timing during the day of incontinence), physical examination (including rectal and neurologic examination), serum biochemistry profile, urinalysis, urine culture, abdominal radiographs and ultrasonography.

Diagnosis and management of the majority of cases are routine; however, treatment of refractory urinary incontinence cases are frustrating for both the veterinarian and owner. The diagnostic approach to dogs with refractory urinary incontinence should include a thorough history (drugs, age of onset, and timing during the day of incontinence), physical examination (including rectal and neurologic examination), serum biochemistry profile, urinalysis, urine culture, abdominal radiographs and ultrasonography. Cystoscopy and urodynamic testing including urethral pressure profile (UPP) and cystometrogram (CMG) are recommended if available.

Urethral incompetence

Urethral incompetence is the most common cause of incontinence in adult female dogs. Urethral incompetence is usually occurs months to years after neutering. Congenital anatomic or functional abnormalities of the urethra may result in urethral incompetence prior to neutering. The pathogenesis of urethral incompetence after neutering likely involves the permissive effects of estrogen on α-adrenergic receptors of the internal urethral sphincter, thereby promoting increased urethral tone and continence. With decreased estrogen concentration, α-adrenergic receptors require greater stimulation to maintain urethral tone. This provides the basis of treatment with α-adrenergic agonists or estrogen. While the dog is awake, continence may be maintained by the external urethral sphincter. When the dog is sleeping or with muscle relaxation, the internal sphincter fails maintain continence resulting in incontinence. In older dogs, development of PUPD from any cause may result in clinical incontinence in dogs with marginal urethral sphincter competence.

One common reason for refractory urinary incontinence is that some dogs become refractory to the effects of long-term administration of α-adrenergic agonists. The α-adrenergic agonist phenylpropanolamine or PPA (1.1—1.5 mg/kg PO q 8 h) is initially effective in approximately 85% of female dogs with urethral incompetence; however, prolonged administration of PPA may cause some down-regulation of the α-adrenergic receptors and decreased efficacy. Pseudoephedrine is less effective than phenylpropanolamine. Phenylpropanolamine should not be used in patients with pre-existing hypertension. The side effects of phenylpropanolamine in dogs include excitability, panting, restlessness, irritability, and hypertension.

Estrogen therapy increases urethral closure pressure theoretically by increasing the density and responsiveness of α-adrenergic receptors in urethral smooth muscle. Estrogen therapy is effective in approximately 65% of female dogs with urethral incompetence. Excessive doses of estrogen may cause severe bone marrow suppression; therefore owners should be cautioned not to exceed recommended doses and complete blood counts should be monitored in dogs receiving estrogen therapy. Diethylstilbestrol is administered at 0.1—0.2 mg/kg PO daily (maximum dose 1 mg/dog) for 5 days followed by the same dose once to twice a week. The maximum maintenance dose of diethylstilbestrol should be 0.1 mg/kg/week. The minimum effective dose should be used for maintenance therapy.

Oral estriol is an alternative to diethylstilbestrol. Estriol is administered at a dose of 2 mg PO daily for a week, then the dose is reduced at weekly intervals to the minimal effective dose (0.5—2.0 mg/dog given daily or every other day).} Estriol treatement resulted in continence in 61% of dogs with an additional 22% of dogs that were improved. Estriol has been marketed for veterinary use in Europe since 2000, and the incidence of adverse effects associated with use of this product appears to be low. Estriol therapy increased urethral pressure in normal dogs, but the effects of estriol on urodynamic measurements have not been reported in dog with urinary incontinence.

Treatment of refractory urethral incompetence:

Estrogen therapy up-regulates the α-adrenergic receptors that phenylpropanolamine stimulates, thus combination therapy with these medications is synergistic. Female dogs that are refractory to either medication alone may respond to combination therapy. For dogs that are refractory to combination therapy, urodynamic evaluation is recommended. Alternative therapies for dogs with refractory urinary incontinence due to confirmed urethral incompetence include cystoscopic injections of bulk-enhancing agents (glutaraldehyde cross-linked collagen) or surgical methods to increase urethral resistance.

Periurethral injection of collagen narrows the urethral lumen and allows for more effective closure of the urethra by existing urethral pressure. Periurethral injection of collagen resolved urinary incontinence in 53 to 69% of dogs without medication. Overall, 75 to 93% of these dogs were improved after peri-urethral collagen injection with or without concurrent administration of phenylpropanolamine. The mean duration of continence following peri-urethral collagen injection was 17 months in one study.

Prior surgical methods for treatment of refractory urinary incontinence included colposuspension and urethropexy. Surgery by these techniques resolved incontinence in approximately 50% of dogs with an additional 25-40% being continent with concurrent administration of phenylpropanolamine. However, long-term evaluation suggested that these techniques had much lower long-term improvement with only 14% of dogs still continent one year after surgery.7 A novel approach to management of refractory urinary incontinence is the surgical placement of a hydraulic urethral sphincter around the urethra. Results of this procedure for treatment of clinically affected dogs with incontinence indicates that it appears more effective than previously reported surgical approaches.

Detrusor instability and urge incontinence

Although urethral incompetence is the most common cause of urinary incontinence, incontinence may also occur due to detrusor contraction during storage of urine or due to low compliance of the detrusor muscle, which may be confirmed by cystometrography. When decreased detrusor compliance occurs secondary to inflammatory conditions affecting the lower urinary tract (e.g., urolithiasis, UTI), this is termed urge incontinence. Clinical signs of dogs with urge incontinence may also include pollakiuria, stranguria and dysuria. If no identifiable cause of decreased detrusor compliance is identified, this is termed idiopathic detrusor instability.

Treatment of detrusor instability is by anticholinergic medications (oxybutynin, imipramine or dicyclomine) to decrease detrusor contractions during storage of urine. Although oxybutynin (0.2 mg/kg PO q 8—12 h) has been most commonly recommended, dicyclomine appeared to have a greater effect on detrusor compliance in normal dogs than oxybutynin. Clinical effectiveness of dicyclomine has not been reported in dogs with idiopathic detrusor instability. Imipramine is a tricyclic antidepressant medication that has anticholinergic effects to facilitate urine storage and also increases urethral closure pressure. Therefore imipramine may be effective for dogs with mixed incontinence due to detrusor dysfunction and concurrent urethral incompetence.

Ectopic ureters

Ectopic ureters are a common cause of urinary incontinence in young dogs. Ectopic ureters may also be diagnosed in adult dogs with refractory urinary incontinence, especially dog with ectopic ureters located in the proximal urethra. Most canine ectopic ureters are intramural in location, meaning the ureter enters the serosal surface of the bladder wall in the correct location, but the intramural ureter tunnels in the wall of the bladder and urethral submucosa with one or more openings in the urethra or vaginal vestibule. Extramural ectopic ureters connect to the urethra or vagina without first tunneling through the bladder and urethral wall.

Although ectopic ureters have traditionally diagnosed by contrast radiography, cystoscopy is the preferred technique for diagnosing ectopic ureters is provided the clinician is experienced with the procedure. In studies comparing the diagnostic accuracy of excretory urography, contrast enhanced CT scans and cystoscopy for detection of ectopic ureters, contrast enhanced CT scans and cystoscopy were the most accurate diagnostic methods for detection of ectopic ureters. During cystoscopy, the anatomy of the urethra and vaginal vestibule are also evaluated. Dogs with ectopic ureters often abnormalities of the vaginal vestibule (e.g., paramesonephric septal remnant) and urethral malformations. We now recommend laser incision to break down these septal remnants at the time of laser ablation of the ectopic ureters, because the septal remnant may contribute to recurrent UTI in some dogs.

Urethral incompetence frequently occurs concurrently with ectopic ureters and can result in treatment failure after repair of ectopic ureters. Because, UPP results can be used to predict post-surgical continence, urodynamic testing should be performed prior to surgical or laser correction of ectopic ureters.

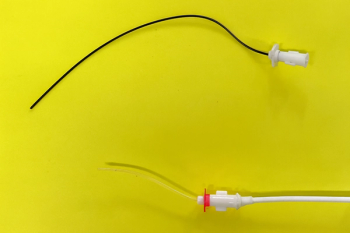

Traditionally various surgical techniques have been used for correction of ectopic ureters. A new technique for treatment of intramural ectopic ureters is to use a diode or holmium: YAG laser to remove the wall between the urethra and parallel ureter. Laser correction of ectopic ureters is effective in dogs, although some dogs also require medical management of concurrent urethral incompetence to resolve incontinence. Laser ablation of intramural ectopic ureters resulted in resolution of urinary incontinence in 5 of 8 female dogs. Additionally, 2 of 8 female dogs were continent with medication or periurethral collagen injections for concurrent urethral incompetence. Laser ablation of ectopic ureters resolved urinary incontinence in 4 of 4 male dogs.

References

Richter KP, Ling GV. Clinical response and urethral pressure profile changes after phenylpropanolamine in dogs with primary sphincter incompetence. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1985;187:605-611.

Scott L, Leddy M, Bernay F, et al. Evaluation of phenylpropanolamine in the treatment of urethral sphincter mechanism incompetence in the bitch. J Small Anim Pract 2002;43:493-496.

Byron JK, March PA, Chew DJ, et al. Effect of phenylpropanolamine and pseudoephedrine on the urethral pressure profile and continence scores of incontinent female dogs. J Vet Intern Med 2007;21:47-53.

Nendick PA, Clark WT. Medical therapy of urinary incontinence in ovariectomised bitches: a comparison of the effectiveness of diethylstilboestrol and pseudoephedrine. Austr Vet J 1987;64:117-118.

Mandigers PJJ, Nell T. Treatment of bitches with acquired urinary incontinence with oestriol. Vet Rec 2001;149:765-767.

Hamaide AJ, Grand JG, Farnir F, et al. Urodynamic and morphologic changes in the lower portion of the urogenital tract after administration of estriol alone and in combination with phenylpropanolamine in sexually intact and spayed female dogs. Am J Vet Res 2006;67:901-908.

Rawlings CA. Colposuspension as a treatment for urinary incontinence in spayed dogs. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2002;38:107-110.

Arnold S, Hubler M, Lott-Stolz G, et al. Treatment of urinary incontinence in bitches by endoscopic injection of glutaraldehyde cross-linked collagen. J Small Anim Pract 1996;37:163-168.

White RN. Urethropexy for the management of urethral sphincter mechanism incompetence in the bitch. J Small Anim Pract 2001;42:481-486.

Barth A, Reichler IM, Hubler M, et al. Evaluation of ling-term effects if endoscopic injection of collagen into the urethral submucosa for treatment of urethral sphincter incompetence in female dogs: 40 cases (1993-2000). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2005;226:73-76.

Adin CA, Farese JP, Cross AR, et al. Urodynamic effects of a percutaneously controlled static hydraulic urethral sphincter in canine cadavers. Am J Vet Res 2004;65:283-288.

Rose SA, Adin CA, Ellison GW, et al. Long-term efficacy of a percutaneously adjustable hydraulic urethral sphincter for treatment of urinary incontinence in four dogs. Vet Surg 2009;38:747-753.

Holt PE. Long-term evaluation of colposuspension in the treatment of urinary incontinence due to incompetence of the urethral sphincter mechanism in the bitch. Vet Rec 1990;127:537-542.

Lane IF. Use of anticholinergic agents in lower urinary tract disease, in Kirk's Current Veterinary Therapy, ed. Bonagura JD, W.B.Saunders, Philadelphia, 2000, 899-902

Cannizzo KL, McLoughlin MA, Mattoon JS, et al. Evaluation of transurethral cystoscopy and excretory urography for diagnosis of ectopic ureters in female dogs:25 cases (1992-2000). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2003;223:475-481.

Samii VF, McLoughlin MA, Mattoon JS, et al. Digital fluoroscopic excretory urography, digital fluoroscopic urethrography, helical computed tomography, and cystoscopy in 24 dogs with suspected ureteral ectopia. J Vet Intern Med 2004;18:271-281.

Lane IF, Lappin MR, Seim HB. Evaluation of results of preoperative urodynamic measurements in nine dogs with ectopic ureters. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1995;206:1348-1357.

Berent, A. C. and Mayhew, P. Cystoscopic-guided laser ablation of ectopic ureters in 12 dogs. J Vet Intern Med 2007;21:600 (A).

Berent AC, Mayhew PD, Porat-Mosenco Y. Use of cystoscopic-guided laser ablation for treatment of intramural ureteral ectopia in male dogs: four cases (2006-2007). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2008;232:1026-1034.

Newsletter

From exam room tips to practice management insights, get trusted veterinary news delivered straight to your inbox—subscribe to dvm360.