Updates on leptospirosis (Proceedings)

Leptospirosis is a re-emerging disease worldwide.

Leptospirosis is a re-emerging disease worldwide. Leptospirosis is caused by multiple serovars of Leptospira interrogans or by Leptospira kirschneri serovar grippotyphosa. It is a filamentous, motile bacteria. Each serovar is maintained by one or more natural hosts. Clinically important serovars and their normal hosts for North America include canicola (dog), ictero-haemorrhagiae (rat), grippotyphosa (vole, raccoon, skunk, opossum), pomona (cow, pig, skunk, opossum), hardjo (cow), bratislava (rat, pig, potentially horse), and potentially autumnalis (mouse). Host-adapted species do not usually develop disease from the serovar they carry, but infection in an incidental host can cause severe disease.

Transmission and pathogenesis

The primary method of transmission is via water contaminated with urine, although urine-contaminated soil, bedding and food are also routes of exposure. Exposure to urine, blood, or saliva can also transmit disease. The organism prefers a warm, moist, alkaline environment, and is more likely to be present in stagnant or slow moving water. The organism can persist for several months in an appropriate environment. An increase in incidence is common following periods of flooding or heavy rainfall. Peak incidence in dogs is from July-Nov. Adult large breed male dogs with access to outdoors are more likely to contract leptospirosis.

Organisms can penetrate mucus membranes, wet or macerated skin, or intact skin. They replicate in various organs, preferentially including the kidneys, liver, spleen, central nervous system, eyes, and genital tract. The incubation period is usually 5 to 7 days but may vary. Antibody production appears around day 7-8 and the organism is cleared from most organs except the kidneys. The organism replicates and persists in the renal tubular epithelial cells, causes shedding for weeks to months following infection is antibiotics are not used to eliminate organisms from the kidney.

Clinical signs

Leptospirosis may present as a peracute, acute, subacute, or chronic disease. Peracute disease is associated with massive leptospiremia, and death occurs with few premonitory signs. Definitive diagnosis is difficult during this stage, but it appears to be uncommon. The initial signs of acute disease are typically pyrexia, shivering, and muscle tenderness. These signs are subsequently followed by signs of vomiting, dehydration, shock, tachypnea, and coaguation defects. These patients die before kidney or liver failure occur. Serology would be negative due to the short time frame from exposure to death.

Subacute disease is the most commonly recognized form of leptospirosis. The signs affect multiple body systems, and include fever, anorexia, dehydration, injected mucus membranes, and petechial and ecchymotic hemorrhages. Musculoskeletal manifestations include reluctance to move, paraspinal hyperesthesia, stiffness, arthralgia, and myalgia. Conjunctivitis, uveitis, or meningitis may be present. Gastrointestinal signs can be quite profound, and include vomiting, diarrhea, and intussusception. Common signs of renal involvement include initial polydipsia and polyuria, which can progress to oliguria or anuria. Less severe cases may have massive polyuria. Swollen, painful kidneys may be present. Icterus occurs from intrahepatic cholestasis and hepatic necrosis. Respiratory signs may include rhinitis, tonsillitis, cough, dyspnea, and interstitial pneumonia.

Survivors of the acute or subacute form of leptospirosis may develop chronic renal or hepatic disease. The chronic renal disease is characterized by interstitial nephritis with fibrosis. In the liver, chronic active hepatitis with inflammation and fibrosis may lead to hepatic failure.

Young dogs (< 6 months) seem to have more severe clinical signs and are likely to have more severe liver involvement than adult dogs. Subclinical infection without any clinical signs can occur.

Diagnosis

Most dogs (87-100%) with leptospirosis present in renal failure, although leptospirosis is suspected because of renal failure, and dogs without renal failure may not be routinely tested for leptospirosis, skewing the population sample. Hyperphosphatemia and low concentrations of calcium, sodium, chloride, and potassium occur frequently. Hyperkalemia may be present with terminal anuria. Metabolic acidosis is present, due both to renal failure and dehydration. The hepatic involvement is usually less severe than the renal involvement, and includes elevations in alkaline phosphatase, ALT, AST, and bilirubin. The peak increase in hepatic enzyme elevation is usually 6-8 days after the onset of renal disease. Urinalysis shows a typical picture of acute renal failure, with glucosuria, proteinuria, and an active urine sediment, including low numbers of white blood cells, red blood cells, and granular casts. Leukocytosis with or without a left shift is common. Leukopenia may be present in the leptospiremic phase, but is rarely detected. Thrombocytopenia is common with serovar icterohaemorrhagiae, but may also be present in conjunction with DIC.

Thoracic radiographs frequently reveal an interstitial pattern in the caudal dorsal lung fields, which is caused by pulmonary hemorrhage and interstitial pneumonia. Abdominal ultrasonography is consistent with acute renal failure. The kidneys may appear normal or have renomegaly. There may be increased cortical echogenicity. A bright demarcation between the cortex and medulla ("medullary rim sign") and perinephric effusion have been reported in dogs with leptospirosis, but these findings are not specific for leptospirosis.

The standard serologic test is the microscopic agglutination test (MAT). It detects specific serovars, but there is much cross-reactivity between serovars. A four-fold rise in titer between the acute and convalescent (2-4 weeks later) samples confirms the diagnosis. A single titer of 800 or higher (with clinical signs and absence of recent vaccination) provides a presumptive diagnosis. Early antibiotic therapy may decrease the magnitude of antibody titer. Vaccinal titers of greater than 800 usually do not persist for more than 3 months past vaccination.

A polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test for leptospires in the urine is commercially available. It may be a more sensitive test, and detect the disease earlier in the course compared to the MAT, as it detects DNA from the leptospiral organisms instead of an immunologic reaction to the organisms. It does not differentiate between the different serovars.

An ELISA test for rapid detection has been developed for people, but it does not distinguish between serovars. Darkfield microscopy of urine samples may detect leptospiral organisms, but both false positives and false negatives are common. Culture of the organism from urine or tissue is difficult and time-consuming. Typical histopathologic changes in the kidney include predominantly lymphoplasmacytic interstitial changes. Silver stain is necessary to see the leptospires, and they may be difficult to detect if antibiotic therapy has been administered.

Treatment

General therapy

Patients presenting in shock should be treated with aggressive intravenous fluids. Dehydration should be corrected over 6-24 hours. After the initial resuscitation, maintenance fluids (60 ml/kg/day) plus and additional 2.5-5% of body weight/day should be administered to maintain a diuresis. If the patient has massive polyuria or significant vomiting, additional fluid may need to be administered. If the dog is in an anuric or oliguric state (i.e <1 ml/lb/hr), the "ins-and-outs" method of fluid administration should be used.

If volume expansion is adequate, blood pressure is above 80 mmHg systolic, and urine production is still below 1 ml/lb/hr, a diuretic could be considered. Furosemide is the most potent diuretic available. A dose of 2-8 mg/kg intraveneously usually will increase urine output in 20-60 minutes if this drug is going to be effective. Mannitol (0.25-0.5 gm/kg IV over 20 minutes) is an osmotic diuretic that may be beneficial.

In addition to fluid management, medications to control signs of uremia are indicated. GI protectants like histamine blockers (ranitidine, famotidine) or proton pump blockers (omeprazole, pantaprazole) and/or sucralfate are helpful. Vomiting is frequently severe with leptospirosis, and antiemetics (metoclopramide, chloropromazine, ondansetron, meropitant) may be necessary.

Specific therapy

Penicillin and its derivatives and doxycycline are very effective in eliminating the leptospiremic phase, and are an excellent initial choice. However, the penicillins do not eliminate the carrier state. Doxycycline is effective against the carrier state, as is erythromycin and azithromycin . Treatment should be continued for at least 4 weeks. Many patients initially cannot withstand oral medications due to vomiting, making injectable penicillin drugs convenient. Doxycycline can be given intravenously, but needs to be given slowly in a large volume of fluid, and should be protected from light during infusion.

Advanced Therapy

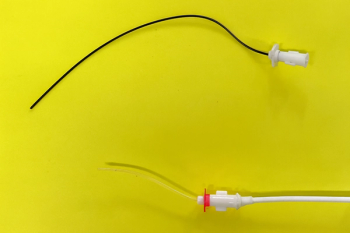

Patients with unresponsive oliguria or anuria, hyperkalemia, or life-threatening volume overload (pulmonary edema) may benefit from dialysis. In this setting, dialysis is used to manage the renal failure while giving antibiotics time to clear the leptospiremia and allow recovery of renal function. Peritoneal dialysis or hemodialysis can be used.

Vaccination

Available vaccines are serovar-specific and are not cross-protective against other serovars. Vaccines for serovars canicola and icterohaemorrhagiae have been available for 20 years, but use waned because of the rate of adverse reactions. Newer vaccines are now available which include the serovars canicola, icterohaemorrhagiae, pomona and grippotyphosa. Advances in manufacturing process have helped to decrease the portions of the vaccine that elicited adverse reactions while enhancing the protective actions. The initial series should include at least 2 injections 3-4 weeks apart. Older vaccines needed to be administered twice a year; one of the new quadrivalent vaccines has recently been shown to provide protective immunity for at least a year.

Because the risk of adverse reactions to the vaccine is now quite low, vaccination should be recommended for any dog in an endemic area, and is particularly advised for dogs with access to outdoors (yard, dog park, etc.)

Zoonotic potential

Leptospirosis is a zoonotic disease. Pet owners and hospital staff members should be informed of the transmission potential. People handling patients or urine should wear gloves and wash hands after any contact. A urinary catheter and urine collection bag may decrease urine contamination of the environment. Dogs should not be allowed to urine in areas frequented by other dogs, and these areas should be thoroughly disinfected and dried. Caution is advised when cleaning cages to avoid splashing urine, and protective eyegear may be warranted. However, the leptospiral organisms cannot withstand most disinfectants or drying.

Outcome

Leptospiremia is usually very responsive to antibiotic therapy. Survival rate is reported to be 80-90%. Possible outcomes include complete recovery, chronic renal failure, and the infrequent late consequence of chronic active hepatitis.

Newsletter

From exam room tips to practice management insights, get trusted veterinary news delivered straight to your inbox—subscribe to dvm360.