Urinary incontinence in dogs (Proceedings)

Urinary incontinence is a common problem that is very vexing to clients, and frequently to veterinarians.

Introduction

Urinary incontinence is a common problem that is very vexing to clients, and frequently to veterinarians. Micturition is defined as the process by which the bladder empties after becoming filled. Micturition disorders may involve failure of the filling stage or failure of the voiding stage. In order to understand the disorders and the potential therapies, a review of the anatomy and neurologic control of micturition is necessary.

Anatomy

The bladder contains a layer of smooth muscle, the detrusor muscle, which contracts during micturition. The internal urethral sphincter is located at the neck of the bladder in female dogs, and in the prostatic urethra (also at the neck of the bladder) in male dogs. The internal sphincter is smooth muscle, and is therefore not under voluntary control. The external urethral sphincter is composed of striated muscle, and thus is the voluntary portion. It is short in female dogs and is located in the midurethra portion. The external sphincter in male dogs is in the membranous urethra, and because it is longer, male dogs have more voluntary control in micturition, which is undoubtedly important in marking behavior.

Innervation: The regions of the central nervous center that are involved in micturition include the frontal cerebral cortex (for consciousness of micturition events), thalamus (conditioned micturition), brain stem micturition center (coordination of micturition), sympathetic nervous system at L1-L4, parasympathetic nervous system at S1-S3, and somatic system at S1-S3. The sympathetic nervous system (SNS) is served by the hypogastric nerve. The parasympathetic nervous system (PSNS) is served by the pelvic nerve. The pudendal nerve carries somatic information.

Sensory innervation of the bladder detects fullness and stretch. These impulses are relayed via the pelvic nerve to the brain stem micturition center and to higher center via the thalamus. Receptors in the submucosa detect extreme distension and relay pain sensation via the pelvic and hypogastric nerves. Sensory information from the urethra is carried by the pudendal nerve.

Micturition Reflex: During the storage phase, α-adrenergic stimulation via the hypogastric nerve (SNS) maintains internal urethral sphincter contraction. The external urethral sphincter maintains constant tone. Beta-adrenergic stimulation (SNS) inhibits detrusor contraction, allowing low pressure filling. When the bladder fills, stretch receptors signal the brain stem micturition center. Voluntary micturition involves abdominal contraction and relaxation of the perineal musculature. Increased parasympathetic tone to the bladder leads to contraction of the detrusor muscle. Initiation of contraction leads to inhibition of α-adrenergic tone to the internal urethral sphincter, and -adrenergic stimulation for detrusor inhibition. Storage is under sympathetic control, voiding is a parasympathetic activity.

Causes of Incontinence

Failure of urine storage usually results in the animal maintaining a small bladder and displaying incontinence. Failure of voiding usually results in the animal maintaining a large bladder or having incomplete emptying and may result in incontinence.

Small Bladder Incontinence

Primary Urethral Sphincter Mechanism Incontinence: This disorder is also known as spay incontinence or estrogen responsive incontinence. The actual cause is not clearly known, but theories include estrogen deficiency, vaginal stump adhesions that interfere with sphincter activity, damage to supporting structures of the bladder, pelvic bladder, and obesity. This is the most common cause of incontinence in the spayed female dog. It occurs within days to years of ovariohysterectomy, and it also occurs in unspayed dogs. Large breed dogs are more likely to be affected than small breed dogs. The incontinence is usually worse when the dog is lying down or asleep.

Ectopic Ureter: Continual incontinence starting at birth or a very early age is typical of ectopic ureters. The ureters bypass the bladder and open into the urethra, usually at a point distal to the internal sphincter. Occasionally, intermittent or positional incontinence has been described.

Patent Urachus: Drips urine from ventral abdomen from birth.

Vaginal Anomalies: Some vaginal anomalies, like vestibulovaginal constrictions, vaginal bands or rectal/vaginal-urethral fistulas have been associated with urine pooling and incontinence. Positional changes (i.e., standing up from a recumbent position) cause urine leakage. Most of these dogs also have a functional disturbance that accounts for the incontinence.

Urinary Tract Infection: The inflammation associated with a urinary tract infection can cause a sensory hyperreflexia in the bladder, leading to involuntary hypercontractility. Other signs of urinary tract infection, including pollakiuria and stranguria are usually present.

Infiltrative Bladder Disease: Lesions that affect and irritate the bladder wall, like chronic cystitis, neoplasia, urolithiasis, can cause urinary incontinence. As with a UTI, others signs of lower urinary tract disease like pollakiuria, hematuria, stranguria, and dysuria are usually present.

Prostatic Disease: Because the internal urethral sphincter is located within the prostate, any sort of prostatic disease can lead to incontinence.

Congenital Bladder Hypoplasia: This is a rare condition that reduces bladder storage function.

Detrusor Instability (Urge incontinence): This is a common condition in women, and it has been described in dogs. It is rare as a primary cause of incontinence in veterinary medicine, but is can be secondary to infection, inflammation, or an idiopathic condition.

Large Bladder Incontinence

Lower Motor Neuron Disease: A lesion of the sacral spinal cord, sacral nerve roots, or pudendal nerve can affect the parasympathetic innervation of the bladder, impairing detrusor muscle contraction. Internal sphincter tone can remain intact since the hypogastric nerve originates from the lumbar segments. As the bladder distends, the intravesicular pressure becomes great enough to overcome the sphincter pressure, and overflow incontinence results. Because the sensory component of the urethral innvervation is disrupted by sacral lesions, the internal sphincter does not respond to increased bladder pressure. The bladder tends to be distended and flaccid but easily expressed. Other signs of sacral lesions (i.e., paraparesis or paralysis, decreased anal tone and perineal reflexes, fecal incontinence, and loss of tail tone) are usually present.

Upper Motor Neuron Disease: Lesions of the thoracolumbar region or higher can result in urinary dysfunction characterized by a distended, firm bladder that is difficult to express. Loss of inhibition of pudendal nerve activity causes a urethral sphincter hyperreflexivity. Bladder function is lost. If the pelvic and pudendal nerves are intact, reflex detrusor contraction occurs but may not be coordinated with sphincter relaxation, resulting in interrupted, incomplete urination and urine retention. Other signs of thoracolumbar disease (proprioceptive deficits, paraparesis or tetraparesis, ataxia, and hyperreflexia) may be present.

Brain Stem Lesions: Brain stem lesions cause bladder signs similar to an upper motor neuron disorder. Other signs of brain stem disease, like change in mental status, gait, posture, and cranial nerve deficits may be present. Lesions higher than the pons affect voluntary urination. Unconscious urination, nocturia, and urination in inappropriate places are common signs.

Detrusor Atony: A distended flaccid bladder that is easily expressed is the characteristic of detrusor atony. Dogs may posture to urinate and apply abdominal press yet fail to produce an adequate urine stream. As the bladder becomes distended, overflow incontinence results. Causes of detrusor atony include neurologic disease or obstruction. With neurologic disease, there is a failure to initiate contraction. With obstruction, which can be acute or chronic, and complete or partial, the overdistension of the bladder stretches the detrusor muscle, damaging the tight junctions, rendering it incapable of contraction. This condition may also be seen with dysautonomia, a very rare condition that affect the autonomic nervous system.

Urethral Obstruction: A partial urethral obstruction may cause a paradoxic incontinence. Because there is obstruction to urine outflow, residual bladder volume after voluntary micturition is high. As the volume in the bladder increases, the pressure overcomes the urethral resistance and incontinence results. Causes of obstruction include urolithiasis, neoplasia, stricture, granulomatous urethritis, and prostatic disease.

Detrusor-Urethral Dyssynergia: In this condition, there is lack of coordination between the relaxation and contraction phases of micturition. The urethral sphincter fails to relax and open during detrusor contraction.

Diagnostic Tests

A thorough history and description of the pattern of urination helps select appropriate differential diagnoses for a micturition disorder. This frequently involves careful questioning of the owner or caretaker. Bladder size on physical examination helps divide cases of incontinence into large bladder or small bladder. Other information to gather by physical examination includes neurologic function, particularly evaluating for proprioception, anal tone, perineal reflex, and tail tone. A wet perineum, perineal staining, or urine scalding is evidence of incontinence. Rectal palpation detects prostatic disorders and urethral thickening that may suggest neoplastic or granulomatous infiltration. A digital vaginal exam may reveal strictures or mass-like lesions.

For patients with a large bladder on presentation, manual expression of the bladder gives an indication of urethral resistance. Measurement of residual urine volume after voluntary voiding helps localize the lesion. Easy of urinary catheterization can sometimes localize a lesion or establish that the lesion is functional, not structural.

Urinalysis provides indications of urinary tract infection or inflammation. A urine culture will reveal urinary tract infections that may be causing the incontinence or may be a result of the incontinence. A serum chemistry panel will help evaluate for renal damage from urinary obstruction.

Unless radioopaque calculi are present, survey abdominal radiographs are unlikely to reveal the cause of the incontinence. However, because uroliths are a common disorder, radiographs are a prudent screening tool. It is important to include the entire urethra in the view to avoid overlooking a lesion. Ultrasonography is a non-invasive method of structural evaluation the lower urinary tract that can visualize bladder neoplasia, bladder wall thickness, and intraluminal structures such as calculi. It cannot evaluate the urethra. An intravenous pyelogram (IVP) highlights the ureters during the later stages of the study, allowing evaluation of position and entrance into the bladder or beyond. Combining an IVP with negative contrast cystography allows even better visualization of the ureter entrance into the bladder searching for an ectopic ureter.

The cystourethrogram is one of the most sensitive methods of detecting structural abnormalities of the bladder and urethra that may be causing incontinence. Both double contrast and positive contrast studies should be performed. In some cases, vaginourethrography will be helpful in discovering or excluding structural malformations.

Cystoscopy can be a valuable tool in evaluating incontinent dogs and possibly cats. Ectopic ureters that enter the bladder at a normal location and tunnel submucosally to open distally may not be detected by IVP but can be seen cystoscopically.

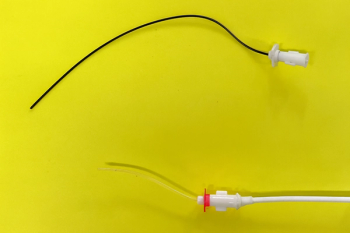

Functional evaluation of incontinence can be accomplished with a urethral pressure profile and cystometrography. A cystometrogram is performed in an awake or light sedated (not anesthetized) dog by placing a urinary catheter in the bladder. Saline is infused into the bladder while simultaneous pressure measurements of the intravesicular pressure are made. In the normal bladder, there will be a phase of filling with low intravesicular pressure, followed by a period of increasing pressure as the bladder wall becomes distended and stretches. The intravesicular pressure that elicits a micturition reflex can thus be recorded. Dogs with detrusor instability will void at lower pressures and lower saline infusion volumes, whereas a dog with detrusor atony will allow large volumes of infusion with minimal increase in pressure, and the micturition reflex does not generate a spike in the intravesicular pressure. Urethral pressure profilometry involves slowly removing a catheter through the urethra, measuring pressure along the length of the urethra. When the tip of the transducer is located at the urethral sphincter, the pressure should be higher than the surrounding urethra. Changes in this pressure, particularly extremely low values, indicate sphincter dysfunction.

Treatment

Correction of any structural disorders identified with the diagnostic work-up will likely be necessary to cure the incontinence (e.g., cystotomy for cystic or urethral calculi). In many cases, however, correction is not possible (e.g., extensive infiltrative urethral neoplasia) or does not result in complete resolution of the incontinence (e.g., sphincter damage secondary to ectopic ureter despite reimplantation into the bladder). Incontinence caused by inflammation secondary to urinary tract infection should resolve as the UTI is controlled. With many neurologic disorders, supportive care is paramount to managing the bladder and avoiding complications. Chronic urine retention leads to detrusor atony, which can be a permanent disorder that persists even after improvement of the primary neurologic lesion. Chronic urine retention also leads to recurrent infection, which can become resistant if inappropriate or inadequate antimicrobial therapy is used. Many patients with chronic urine retention develop resistant infections despite appropriate therapy.

Medical management can be used for certain functional disorders, as an adjunct to supportive care or surgical correction, or for palliation for cases where there is no effective therapy for the underlying cause.

Medical Therapy for Storage Disorders

Phenylpropanolamine: PPA is an alpha-adrenergic receptor stimulator that increases internal urethral sphincter tone. It is used extensively for primary urethral sphincter mechanism incompetence. Side effects include hyperactivity and hypertension. Because receptors may down regulate with time, this drug may become ineffective with time, but discontinuing therapy for 3 weeks allows regeneration of receptors, and the drug will again be effective.

Ephedrine and Pseudoephedrine: This is an alpha-adrenergic receptor stimulator similar to phenylpropanolamine. It has more side effects than PPA but is used when PPA is not readily available

Diethylstilbestrol (DES): The mechanism by which DES works is unknown. It is useful for primary urethral sphincter mechanism incompetence and has the advantage of less frequent administration compared to PPA. DES is given daily for 5 days, then once to twice weekly to maintain continence. At this dose, side effects of bone marrow suppression and aplastic anemia are unlikely. Signs of estrus may occur, however. It can be used in conjunction with PPA. Because DES is no longer commercially available, conjugated estrogens such as Premarin are used.

Estradiol cypionate (ECP): This and other repositrol estrogens are contraindicated because of potential for bone marrow toxicity.

Testosterone cypionate (Depo-testosterone): Male dogs with sphincter incompetence that are not completely controlled with PPA may benefit from monthly repositrol testosterone injections. This drug exacerbates prostatic disease, perianal adenoma, and perineal hernias in castrated males. It can also have adverse behavioral effects. It is now a controlled drug.

Propantheline (Probanthine): Dogs with urge incontinence from detrusor instability may benefit from this drug. Propantheline is an anticholinergic drug that reduces smooth muscle contractions (particularly the detrusor muscle), thus allowing better filling of the bladder. Side effects include dry mucus membranes, constipation and bladder overdistension.

Oxybutinin (Ditropan): This is an anticholinergic and antispasmodic for smooth and skeletal muscle that can also be used for urge incontinence. It is also helpful with cats after an episode of urethral obstruction from FLUTD. Side effects include intestinal ileus. Tolterodine (Detrol), solifenacin (Vesicare), and darifenacin (Enablex) are anticholinergic drugs used for urge incontinence in people.

Emptying Disorders

Phenoxybenzamine (Dibenzyline): Phenoxybenzamine is an alpha-adrenergic blocking agent that allows relaxation of the internal urethral sphincter. It is helpful in cases of outflow resistance due to urethrospasm (urethral calculus, urethritis, upper motor neuron disease). Hypotension is one of its side effects. It takes about 3 days to achieve a therapeutic effect.

Diazepam (Valium): Diazepam's use in disorders of micturition is due to its effect as a centrally acting skeletal muscle relaxant which may reduce external sphincter tone. It has a short lasting effect when given orally and must be dosed three times daily. Side effects include sedation.

Bethanechol (Urecholine): Bethanechol is a strong muscarinic agent that stimulates cholinergic detrusor receptors to result in contraction. It is utilized for bladder atony. Because it also has a weak nicotinic effect, it produces alpha-adrenergic activity to increase urethrospasm. Therefore, always combine therapy with phenoxybenzamine. Consider catheterization during initial treatment.

Surgical/Other Therapy

Colposuspension or urethropexy surgery has been used to decrease incontinence when medical management has failed. Although long-term continence is not usually achieved with surgery, clinical signs are usually ameliorated.

Cystoscopic injection of collagen or Teflon has been used for primary urethral sphincter incompetence. Success rates of 50-75% have been reported, and although relapse appears common, repeated treatment can be used. This will likely become a more common place treatment for dogs that do not respond to medical therapy.

Newsletter

From exam room tips to practice management insights, get trusted veterinary news delivered straight to your inbox—subscribe to dvm360.