Urolithiasis in small ruminants (Proceedings)

Urinary calculi, or uroliths, are concretions of solid mineral and organic compounds that cause disease through direct trauma to the urinary tract and obstruction of urinary outflow. The urethral process is the most common site of obstruction in sheep and goats.

Urinary calculi, or uroliths, are concretions of solid mineral and organic compounds that cause disease through direct trauma to the urinary tract and obstruction of urinary outflow. The urethral process is the most common site of obstruction in sheep and goats.1 In small ruminants that lack a urethral process (as a result of previous surgical removal or necrosis), the distal aspect of the sigmoid flexure is the usual site for blockage. In camelids, uroliths tend to become lodged at or distal to the distal aspect of the sigmoid flexure. Multiple calculi are usually present in the urinary tract of affected small ruminants.1

History and Clinical Signs

The sources of discomfort in acute urethral obstruction appear to be traumatic injury to the urinary tract epithelium and bladder distention following obstruction. However, the presenting complaint provided by the owner or caretaker may have little apparent relation to urinary tract disease. In a case series of 94 cases of urolithiasis admitted to the Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital at the University of California at Davis, anorexia and bloat were the most common primary clinical complaint at admission.2 Owners of affected animals frequently misinterpret these clinical signs as being reflective of an acute gastrointestinal disorder. Owners of camelids appear to commonly misinterpret stranguria as tenesmus. The African Pygmy goat may be predisposed to urinary tract obstruction, as this breed had significantly higher representation in urolithiasis admissions than other breeds.

As the animal postures repeatedly to urinate, the tail may be seen to "pump" up and down as the animal strains to void urine. These forceful voiding attempts may result in frequent passage of small volumes of urine or no urine at all. As bladder distention progresses, the animal may tread, stretch, and kick at its abdomen. Vocalization is common in goats experiencing pain during urination attempts. Blood or crystals may be adhered to the preputial hairs. Signs of pain usually subside upon rupture of the bladder or urethra. The empty bladder is no longer palpable. Anorexia and lethargy ensue, accompanied by progressive ascites or ventral abdominal wall edema with bladder or urethral rupture, respectively.

Confirmation of the diagnosis can be achieved by deep abdominal palpation in sheep and goats. Using the fingertips of both hands placed in the flanks, the examiner gently presses each hand toward the midline. A firm, spherical mass can be palpated in the caudal abdomen in obstructed sheep and goats that have an intact bladder. If the bladder is not palpable, transabdominal ultrasonographic examination may reveal rupture of the bladder. Given that camelids have a less pliant abdominal wall than sheep and goats, confirmation of a diagnosis of urolithiasis in llamas and alpacas requires transrectal or trans-abdominal ultrasonographic examination.

Surgical Treatment

The urethral process should be examined in all cases of suspected urolithiasis in small ruminants. Sedation and/or lumbosacral epidural anesthesia facilitate penile extrusion. The author prefers diazepam (0.1- 0.5 mg/kg IV, slowly) to provide sedation and butorphanol (0.1 mg/kg IV) for analgesia. Once sedated, the sheep or goat should be propped up on its rump. The examiner should grasp the penis through the skin at the base of the scrotum (at the level of the rudimentary teats) and force the penis cranially. As the glans protrudes from the prepuce, it can be grasped with gauze, and the penis can be exteriorized completely. If obstructed, the urethral process can be amputated at its base, near the glans of the penis. Removal of the urethral process has no apparent adverse effect on breeding ability or fertility.

In prepubescent animals, the frenulum may limit exteriorization of the penis. The frenulum is the normal anatomic attachment that exists between the penis and the preputial mucosa. It normally breaks down at puberty. This typically occurs at 4-8 months of age in sheep and goats and 1.5-2.5 years of age in alpacas. If present, the frenulum will effectively prevent exteriorizing the penis. The persistent frenulum may be most problematic in prepubertal animals with urolithiasis, animals castrated at a young age, and (rarely) the intact yearling or two year-old ram or buck. If a persistent frenulum is present, one may have to anesthetize the animal and force the penis out of the prepuce for examination or perform a preputiotomy to gain access to the urethral process. With either method, the resultant trauma to the preputial mucosa can cause preputial scarring or stricture in potential breeders.

Immediate restoration of urethral patency (urine voiding and emptying of the distended bladder) has been reported to occur in roughly 50% of urethral process amputations. However, restoration of urethral patency is often transient, as additional calculi in the bladder or urethra often cause recurrent urethral obstruction. This procedure maintained urethral patency for 1 year in only 4 of 14 cases in a California study. Thus, if it is the only procedure performed, urethral process amputation may not result in a long-term cure.

Perineal Urethrostomy

Perineal urethrostomy is a popular surgical method for correction of obstructive urolithiasis in small ruminants. This procedure can be performed with sedation and local anesthesia, epidural anesthesia, or general anesthesia. It is a surgical option for ruminants not intended to be used for breeding. Its primary limitations involve stricture of the stoma and/or recurrent obstruction with additional calculi. These complications can occur within weeks to months after surgery. In four reports, half or more of small ruminants treated with perineal urethrostomy developed these complications in less than 12 months after surgery.

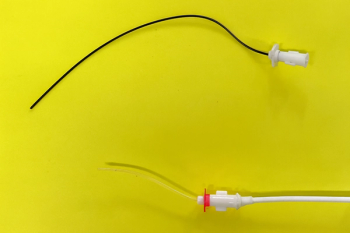

Tube Cystostomy

Currently, tube cystostomy appears to be the most promising procedure for obstructive urolithiasis in small ruminants intended for use as breeding animals or pets. The procedure is relative simple, requiring a short duration of anesthesia, and resulting in restoration of full urethral patency in successful cases. Successful relief of urethral obstruction and discharge from the hospital has occurred in 76%7 to 80% of cases. Despite these successes, tube cystostomy carries its own set of complications, including dislodgement of the catheter, occlusion of the catheter with blood or calculi, and formation of vesicular adhesions. Postoperatively, small ruminants should be fitted with an Elizabethan collar to prevent them from chewing on the catheter. In a Cornell study, complications arose with tube cystostomy that necessitated a second surgical procedure in over half (52%) of 25 goats. Use of larger (18-24 + Fr) catheters for tube cystostomy in small ruminants may limit problems related to occlusion of the catheter. Postoperative vesicular irrigation with sterile, acidic, polyionic solutions (Renacidin®, Guardian Laboratories, Hauppauge NY) placed into the bladder via the cystostomy catheter has been used to facilitate dissolution of calculi remaining in the lower urinary tract in a goat.

Bladder Marsupialization

Bladder marsupialization is often performed if other surgical options are declined or deemed unlikely to succeed. The quality and duration of postoperative life may be limited by such problems as urine scald, urinary tract infection, stricture, and prolapse of bladder mucosa.

Vesicular Irrigation with Walpole's Solution

Walpole's solution is an acidic solution (pH 4.5) comprised of sodium acetate, acetic acid, and distilled water. Veterinarians at Texas A&M University recently reported on vesicular irrigation with Walpole's solution as a means of promoting dissolution of urinary calculi in male goats. Twenty of 25 goats (80%) were treated successfully by this procedure. However, the authors hypothesized that the goats in their study likely suffered from struvite (magnesium ammonium phosphate) calculi, and Walpole's solution may not dissolve other calculus types with similar success. As for other means of treatment of urolithiasis in small ruminants, recurrence of obstruction was noted in some of the goats in this study population. Nonetheless, this technique is easy and inexpensive relative to tube cystostomy, making it a particularly attractive option for short-term resolution of urethral obstruction in goats intended for slaughter.

Prevention

Dilution of calculogenic ions in the urine is of primary importance in prevention of urolithiasis in ruminants. It is important to impress upon owners the importance of encouraging increased water consumption in ruminants at risk for urolithiasis. Adding sugar-free flavoring to the water may encourage increased intake. The water containers should be regularly and vigorously cleaned to maintain water palatability. Allowing access to pasture or browse may increase dietary water intake.

The salt content of the diet can be gradually increased to promote water intake and formation of large volumes of dilute urine. In a Canadian study, loose or lick salt provided free choice proved inadequate for prevention of urolithiasis in animals at risk for silica calculosis. Thus, mixing the salt directly into the feed is the most effective means of delivery. Salt can be mixed in moistened feed or treats (e.g. corn chips with additional salt applied) or sprayed as a saturated solution directly onto hay. As a target quantity, to feed, sodium chloride should be gradually added to the diet to a final level of 3-5% of daily dry matter intake. For an animal weighing 100 kg and ingesting 2% of its bodyweight in dry matter per day, this would translate to feeding 60-100 grams of sodium chloride daily. It is extremely important that a reliable source of water be readily accessible at all times for ruminants on salt-supplemented diets.

As an alternative to salt supplementation, ammonium chloride can be fed at a level of 0.5-1% of dry matter in the diet. At this level, ammonium chloride may induce modest reduction in urine pH, which may render certain calculogenic minerals more soluble in ruminant urine. This salt is unpalatable. For pet animals fed on an individual basis, molasses should be avoided as a flavoring additive for salted rations, as its high potassium content may diminish the acidifying effect of ammonium chloride. Table sugar works well for covering up the flavor of ammonium chloride.

Soybean products treated with hydrochloric acid (SoyChlor,® West Central Cooperative, Inc., Ralston, IA) have been anecdotally reported to appear more palatable to pet small ruminants than ammonium chloride salt. The long-term effects of feeding urinary acidifying agents have not been extensively studied in small ruminants. In mature ewes, however, long-term feeding of anionic salts to induce low-grade metabolic acidosis results in a reduction in bone mineral density. In the author's experience, consistent aciduria can be difficult to achieve through ammonium chloride feeding, owing to changes in the dietary concentration of strong cations and anions that may reflect seasonal or source alterations in forage composition. Empirically, feeding mature small ruminants grass hay rather than legume hay may reduce the urinary concentration of certain calculogenic minerals. Reduction of phosphorus-rich cereal grains and supplements rich in magnesium in the diet might limit formation of phosphate-based calculi. These dietary recommendations should be accompanied by management changes conducive to maximizing water intake. These changes include provision of multiple watering sites, keeping water cool in the summer through placement of water sources in shade, and keeping water from freezing during cold weather. Water should be kept as clean and fresh as possible. Water is best kept in white containers, as this facilitates the owner seeing that the water is becoming soiled and therefore may increase compliance with recommendations to maintain clean and palatable water. Feedlot lambs may be more apt to drink from troughs if the water is left trickling into the trough; apparently, the sound may mimic what the lambs are used to hearing when drinking from streams.

References

VanMetre DC, Smith BP. Clinical management of urolithiasis in small ruminants, Proceedings of the Ninth Annual Forum, American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine, New Orleans, 1991, pp 555-557.

Van Metre DC, unpublished data, 2008.

Haven ML, Bowman KF, Englebert TA, et al. Surgical management of urolithiasis in small ruminants, Cornell Vet 83:47-55, 1993.

Van Weeren PR, Klein WR, Voorhout G: Urolithiasis in small ruminants. I. A retrospective evaluation of urethrostomy, Vet Q 9:76-79, 1987.

Van Metre DC, House JK, Smith BP, George LW, et al. Treatment of urolithiasis in ruminants: Surgical management and prevention. Comp Cont Ed Pract Vet 18: S275-289, 1996.

Rakestraw PC, Fubini SL, Gilbert RO, et al. Tube cystostomy for treatment of urolithiasis in small ruminants, Vet Surg 24:498-505, 1995.

Ewoldt JM, Anderson DE, Miesner MD, et al. Short- and long-term outcome and factors predicting survival after surgical tube cystostomy for treatment of obstructive urolithiasis in small ruminants. Vet Surg 35: 417-22, 2006.

Fortier LA, Gregg AJ, Erb HN, et al. Caprine obstructive urolithiasis: Requirement for 2nd surgical intervention and mortality after percutaneous tube cystostomy, surgical tube cystostomy, or urinary bladder marsupialization. Vet Surg 33:661-667, 2004.

Streeter R, Washburn K, McCauley C. Percutaneous tube cystostomy and vesicular irrigation for treatment of obstructive urolithiasis in a goat. J Am Vet Med Assoc 221:546-49, 2002.

May KA, Moll HD, Wallace LM, et al. Urinary bladder marsupialization for treatment of obstructive urolithiasis in male goats. Vet Surg 27:583-588, 1998.

May KA, Moll HD, Duncan RB, et al. Experimental evaluation of urinary bladder marsupialization in male goats. Vet Surg 31:251-258, 2002.

Janke JJ, Osterstock JB, Washburn KE, et al. Use of Walpole's solution for treatment of goats with urolithiasis: 25 cases (2001–2006). J Am Vet Med Assoc 234: 249-252, 2009.

Bailey CB: Formation of siliceous urinary calculi in calves given supplements containing large amounts of sodium chloride, Can J Anim Sci 53:55-60, 1973.

Stratton-Phelps M, House JK. Effect of a commercial anion dietary supplement on acid-base balance, urine volume, and urinary ion excretion in male goats fed oat or grass hay diets. Am J Vet Res 65: 1391-97, 2004.

MacLeay JM, Olson JD, Enns RM, et al. Dietary-induced metabolic acidosis decreases bone mineral in mature ovarectomized ewes. Calcif Tissue Int 75: 431-437, 2004.

Bushman DH, Emerick RJ, Embry LB: Experimentally induced ovine phosphatic urolithiasis: relationships involving dietary calcium, phosphorus, and magnesium, J Nutr 87:499-504, 1965.

Kallfelz FA, Ahmed AS, Wallace RJ, et al: Dietary magnesium and urolithiasis in growing calves, Cornell Vet 77:33-45, 1987.

Newsletter

From exam room tips to practice management insights, get trusted veterinary news delivered straight to your inbox—subscribe to dvm360.