Vector-transmitted diseases in companion animals: Trends, risks, controls

Mild winters, the northern migration of tick populations and the emergence of more frequent vector-borne zoonotic diseases left the editors of DVM Newsmagazine with questions.

Mild winters, the northern migration of tick populations and the emergence of more frequent vector-borne zoonotic diseases left the editors of DVM Newsmagazine with questions.

We found answers from noted expert Dr. Edward Breitschwerdt, professor of medicine and infectious diseases at North Carolina State University College of Veterinary Medicine and an adjunct associate professor of medicine at Duke University Medical Center. Also, Breitschwerdt co-supervises NCSU's Vector-transmitted Disease Diagnostic Laboratory and remains a principal investigator for the Intracellular Pathogens Research Laboratory. His research emphasis is on the role of vector-transmitted pathogens as a cause of disease in animals and humans.

DVM: The Midwest and North Atlantic regions have experienced very mild winter conditions this year. What risks does that pose for vector-transmitted diseases?

Dr. Breitschwerdt: It is clear that climatic variations contribute to the expansion and contraction of tick populations in various geographic regions. Using Amblyomma americanum as an example, it appears that this tick has moved northward during the past decade. This movement is probably facilitated by expansion in deer populations throughout the eastern United States and the trend of warmer winters.

Factors other than annual temperature also seem to influence the patterns of tick transmission for some pathogens such as Rickettsia rickettsii, the organism that causes Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF) in dogs and people. There seems to be a 10-year cycle of activity relative to peaks in the incidence of RMSF in people; the reason for this cyclic pattern remains unknown.

Unfortunately, despite the fact that dogs are excellent sentinels for many vector-borne organisms, demographic data for vector-borne diseases is frequently not available for dogs.

DVM: In your estimation, what is the most important emerging companion-animal, vector-borne disease threat? Why?

Dr. Breitschwerdt: Babesia gibsoni in dogs and Cytauxazoon felis in cats are perhaps near the top of the list. The range of C. felis transmission appears to be expanding to include most of the southeastern and central United States. As for B. gibsoni, transmission by bites during dog fights appears to represent the most likely means of transmission among Pit Bull Terriers in the United States; however, we are now seeing B. gibsoni-infected dogs that have not been associated with either a Pit Bull Terrier or a fight. Although unproven, this suggests that the brown dog tick, Rhipacephalus sangineus, or other vectors may now be contributing to the transmission of B. gibsoni in the United States.

Research from our laboratory and others suggests that vector-transmitted infectious diseases B. gibsoni and Leishmania infantum have been inadvertently introduced onto the North American continent by dog transport from endemic regions of the world. Many companion-animal infectious disease and public-health veterinarians share a serious concern about the rapid transport of vector-borne organisms throughout the world via infected dogs.

DVM: Could you address the role of Bartonella as a cause of chronic infection?

Dr. Breitschwerdt: The genus Bartonella, which at the time consisted of two known species, was essentially "rediscovered" in the early 1990s as a result of the HIV epidemic. Currently, the genus is comprised of at least 20 species and subspecies, which are vector-transmitted, fastidious, gram-negative bacteria that are highly adapted to one or more mammalian reservoir hosts.

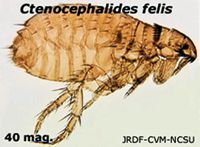

Numerous domestic and wild animals, including bovine, canine, feline, human and rodent species can serve as chronically infected reservoir hosts for various Bartonella species. In addition, an increasing number of arthropod vectors, including biting flies, fleas, lice, sand flies and, potentially, ticks have been implicated in the transmission of Bartonella species. For domestic pets, fleas serve as the vector for Bartonella henselae among cats, and ticks are believed to be the source of Bartonella vinsonii, subspecies berkhoffii transmission to dogs. Because of increased pet ownership and a more intimate relationship between pets and owners, it is possible that Bartonella transmission from pets to people is more frequent than at any time in history. I remain of the opinion that Bartonella species will prove to be an important cause or co-factor in animals and people with chronic debilitating disease.

DVM: Some of your work has focused on leishmaniasis. Could you describe the disease and the current thinking on prevalence?

Dr. Breitschwerdt: Leishmaniasis is a chronic disease of dogs and more rarely cats that is characterized by facial and aural alopecia, cutaneous ulceration, epistaxis, weight loss, vomiting, diarrhea, lymphadenopathy, hyperglobulinemia and a protein-losing nephropathy.

Our limited involvement with leishmaniasis focused on infection in American Foxhounds, which was subsequently shown by investigators at the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) to be endemic in 26 states and southern Canada.

It is clear that the strain of Leishmania infantum that infects dogs in the United States is similar, if not identical, to strains found in southern Europe.

It is probable that this organism was transported to the United States over three decades ago and there has been a smoldering, incompletely recognized, epidemic infection in Foxhounds ever since. There is evidence to support perinatal transmission and transmission during dog fights.

There have also been reports suggesting that the brown dog tick, Rhipacephalus sangineus, can be involved in the transmission of Leishmania species. Experimental studies support vector competence for Lutzomyia shannoni, a sand fly found throughout the southeastern and central United States; however, there is no evidence of natural transmission of Leishmania species to dogs or humans by sand flies.

DVM: What are some of the current research projects you are involved with at NCSU?

Dr. Breitschwerdt: During the past few years, we have focused our research efforts on the enhanced molecular detection and microbiological isolation of Bartonella species from various patient populations. We have made considerable progress in our ability to detect Bartonella spp. if present in a patient sample. As a result, we have documented Bartonella infection in dogs, horses, immunocompetent people, and several marine mammal species.

Because of exceptional evolutionary adaptation, establishing disease causation for various Bartonella species has been an ongoing challenge. We clearly need funding to support larger and more comprehensive studies to sort out the role of these bacteria in complex disease causation.

I believe our research group has now published over 50 scientific manuscripts related to Bartonella infection in animals and human beings. I am very proud of our contributions to date and anticipate that other important observations are in the pipeline.

Ms. Wetzel is a medical freelance writer in Cleveland, Ohio.

Podcast CE: A Surgeon’s Perspective on Current Trends for the Management of Osteoarthritis, Part 1

May 17th 2024David L. Dycus, DVM, MS, CCRP, DACVS joins Adam Christman, DVM, MBA, to discuss a proactive approach to the diagnosis of osteoarthritis and the best tools for general practice.

Listen