Dry Eye in Dogs

A close look at keratoconjunctivitis sicca, including research on new treatments that could be curative for this uncomfortable and often chronic condition.

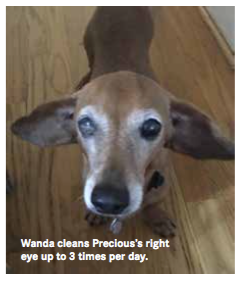

When Wanda Presnell, owner of a dachshund rescue in Raleigh, North Carolina, took custody of 10-year-old Precious in early January, the dog was riddled with health problems, including a urinary tract infection, back issues, heartworms, and, perhaps most troubling, severe bilateral dry eye, which was originally believed to be an infection.

“Her eyes were terribly matted,” Presnell recalled. “There was a pus-like discharge and irritation in both eyes, and she was in severe pain.”

Presnell took Precious to Magnolia Veterinary Hospital in Raleigh, where Jon Dick, DVM, confirmed a diagnosis of dry eye and prescribed tacrolimus aqueous drops.

“It worked great on the left eye,” Presnell said, “but the right eye did not respond at all. A veterinary ophthalmologist in Cary, North Carolina, prescribed tacrosporine NCT, but after a couple of months we saw that it was not working either.”

RELATED:

- Eye Trouble: Infection Risk After Equine Transpalpebral Enucleation

- Who Has Better Vision—Dogs or Cats?

Presnell is still conferring with her veterinary care team to find an effective treatment for Precious’s right eye. In the meantime, she cleans Precious’s eyes 2 or 3 times a day, which eases the dog’s discomfort and makes it easier for her to see. “This is the most significant case of dry eye I’ve had to deal with,” Presnell said. “It’s a real problem.”

Prevalence, Causes, and Clinical Signs

Dry eye, known clinically as keratoconjunctivitis sicca, is almost exclusively a canine health issue, noted Brian Gilger, DVM, MS, DACVO, DABT, professor of ophthalmology at North Carolina State University (NCSU) College of Veterinary Medicine in Raleigh.

Around 5% of dogs will have some level of dry eye during their lifetime,” he reported. “It is seen far less commonly in cats and is almost unheard of in larger animals.”

Michala de Linde Henriksen, DVM, PhD, DACVO, assistant professor of comparative ophthalmology at Colorado State University College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences in Fort Collins, attends to around 20 cases of dry eye a month, including diagnoses and rechecks. The condition can affect all dogs, she noted, but tends to afflict certain breeds more than others, including shih tzus, Boston terriers, English bulldogs, cavalier King Charles spaniels, and West Highland white terriers.

“We believe that the autoimmune type of dry eye is a hereditary disease in specific breeds, but we have not yet found the gene for it, except for the cavalier King Charles spaniel,” Dr. Henriksen said. “The gene for curly coat syndrome and dry eye has been identified by a research group with the Animal Health Trust in Kentford, United Kingdom. They also determined that this gene does not cause dry eye in any other breed of dog."

The signs of dry eye are fairly telltale, reported Dr. Gilger, and include reduced tear production; a thick, mucoid discharge; redness and irritation of the eye tissue; and noticeable discomfort that is sometimes indicated by squinting. “Clients often think their pets have an eye infection, but it’s really dry eye developing,” Dr. Gilger noted.

Pet owners may question a diagnosis of dry eye because of the discharge—how can the eye be dry when there’s so much fluid?—and it’s the veterinarian’s responsibility to explain that the discharge is the result of irritation and is not an ocular lubricant.

Forms of Dry Eye

Spontaneous dry eye is the most common form of the condition, but there are others, known as qualitative tear film deficiencies, that are characterized by a lack of mucin or other important tear components, Dr. Gilger said. In addition, a small percentage of dogs are born with an ocular defect that inhibits tear production in sufficient quantity. Although relatively rare, the condition is considered serious because it does not respond to conventional treatments.

Most cases of spontaneous dry eye are immune mediated, Dr. Henriksen said, which means the patient’s immune system is attacking the lacrimal glands and adversely affecting tear production. In others, the nerve to the lacrimal gland may stop working, causing tear production to cease.

that dogs living in dry, dusty, windy regions are at greater risk for developing dry eye than are dogs living in less extreme environments. Dogs that enjoy sticking their head out of the car window during drives are also at greater risk.

Dry eye can have a dramatic impact on a dog’s quality of life, which is why it should be diagnosed and treated as early as possible. Mildly uncomfortable in the earliest stages, untreated dry eye can lead to blindness as a result of corneal fibrosis, corneal pigmentation, and potentially excruciating abrasions and corneal ulcerations that can become infected and eventually perforate, Dr. Henriksen said. In addition, the continuous mucoid discharge associated with dry eye can make it extremely difficult for a dog to see clearly, which is why regular cleaning is recommended.

Diagnosis and Treatment

A diagnosis of dry eye is typically based on observed signs, such as mucoid discharge and tissue inflammation, and can be confirmed with certainty using the Schirmer tear test. This simple test involves placing a small piece of filter paper on the patient’s eye for 1 minute and measuring the amount of tears that are produced. Minimal tear production usually confirms dry eye.

Treating dry eye in dogs depends on the type and severity of the condition. In most cases, treatments are very similar to those used in humans. “Mild tear deficiencies can usually be well managed with an OTC lubricant, or artificial tears,” which is the go-to treatment for people as well, observed Dr. Gilger. “It’s a little bit more challenging in a dog,” he added, “because dogs don’t express very well when they have mild irritation, so owners tend to undertreat their pets when using artificial tears.”

Veterinarians usually become involved when dry eye progresses from mild to moderate or severe. The standard of care in such cases is immunosuppressant drugs, such as cyclosporine and tacrolimus, which are typically administered once or twice a day to restore function in the lacrimal glands.

“Cyclosporine has been around for nearly 30 years and is kind of the hallmark treatment that showed that dogs and humans are similar when it comes to this condition,” Dr. Gilger said. “Restasis [a treatment for dry eye in humans] is a form of cyclosporine that was first used in dogs years ago, then was developed for use in people. And since then, almost every product approved for people has gone that route, including lifitegrast, which is the newest drug approved for people.”

A higher concentration of immunosuppressive medication is often required because dogs don’t take up the medication quite as well as people, added Dr. Henriksen. Restasis, for example, contains 0.002% cyclosporine compared with 0.2%, and even up to 1% or 2%, in veterinary compounds.

Research is ongoing into implantable drug-release devices that would eliminate the need for daily drops. At the NCSU College of Veterinary Medicine, for example, Dr. Gilger is involved in the study of a ring that fits under the eyelids and gradually releases an immunosuppressive drug over a period of months. “It’s a very practical approach,” Dr. Gilger said. “The rings are very well tolerated, and so far the results have been promising.”

In addition to immunosuppressive medications, an anti-inflammatory drug may be used temporarily to reduce redness and irritation. However, veterinarians should ensure that the patient does not have ulcerations when prescribing a corticosteroid because of the potential for harmful side effects, Dr. Henriksen warned. When in doubt, she suggested consulting with a veterinary ophthalmologist.

If medication fails, there is a surgical option, said Dr. Gilger—transposing a salivary gland from the patient’s mouth to the affected eye. “The gland will produce a very watery saliva that acts like tears and can make a huge difference in the quality of life for dogs that don’t respond well to other treatments,” Dr. Gilger noted. “It’s a last-resort surgery, but it’s very effective.”

Promising New Research

There are, Dr. Gilger added, some intriguing areas of research regarding the treatment of canine dry eye, including the use of stem cells and gene therapy. “We know that stem cell therapy can help promote the redevelopment of normal lacrimal gland function,” he said, “and we have some ability to provide gene therapy, which can help induce a more natural ocular surface and promote better dry-eye care. The beauty of these therapies is that they are potentially curative; it’s not just about managing the disease.”

Once treatment has been prescribed, it’s the doctor’s role to ensure that the client is compliant when the patient goes home. “Most of my clients are not only very compliant, but [they are] highly motivated people,” Dr. Gilger said. “Care can be a huge challenge, however, because they must give their pets medication every day and return for follow-up exams. Although the medications are not expensive, it’s an ongoing cost because dry eye is usually a chronic condition and sometimes clients can’t afford it or they don’t have the time to treat their pets as frequently as needed. In cases like that, the patient will have persistent discomfort and ultimately could lose its vision. I’m sure there are a lot of dogs out there that lose their eyesight or are euthanized because they are persistently uncomfortable.”

Working in teaching hospitals, Drs. Gilger and Henriksen see dry eye on an almost daily basis—far more frequently than most veterinarians in private practice. Dr. Gilger encourages community practitioners to consider dry eye and test for tear production whenever they see a patient with ocular discharge and redness.

“Sometimes it can take veterinarians several months to make a definitive diagnosis just because they haven’t thought about dry eye,” he says. “The eye doesn’t have to look physically dry for the dog to have dry eye; it can be just slightly dry.”

Don Vaughan is a freelance writer based in Raleigh, North Carolina. His work has appeared in Military Officer, Boys’ Life, Writer’s Digest, MAD, and other publications.