All bunged up: Unclogging the constipated cat

Uncomfortable for all involved, constipation in cats is solvable once you determine the cause-be it medical or behavioral. All the tools you need to unclog kitties are right here.

Newly updated client handout

We worked with Dr. Margie Scherk to update a client handout on feline constipation. Get it right here.

Straining in the litter box-possibly even crying out or leaving unwelcome hard pellets around the home-constipated felines are uncomfortable. And constipation can interfere with a cat's appetite and even result in vomiting. Traditional approaches to this hard problem include administering enemas, laxatives to soften the stool or increase contractions, dietary fiber, and promotility agents. Could we be missing something really basic? And when should we be concerned about long-term effects of constipation?

CAUSES OF CONSTIPATION

Constipation is a clinical sign that is not pathognomonic for any particular cause. Most commonly, constipation is a result and sign of dehydration. The body is 65% to 75% water, depending on a cat's age and percent body fat. Homeostasis attempts to maintain a consistent cellular and extracellular environment. When cells become dehydrated, the body takes steps to correct the fluid deficit. Drinking more and concentrating urine are helpful, but once those capabilities have been maximized, water is reabsorbed in the colon, resulting in drier stool that is harder to pass. Bearing this in mind, medical therapy might not be the best initial therapeutic approach.

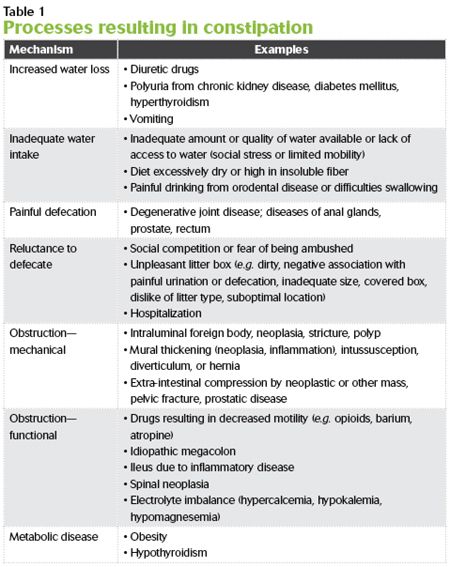

Other causes of constipation include problems that result in obstruction (either mechanical or functional), painful defecation, stress within the home environment (social or a dirty toilet), and possibly metabolic disease (Table 1).

EVALUATING THE PATIENT

History

Given the myriad possible causes as well as concurrent problems, getting an appropriate history is very important. Clients may misinterpret stranguria as tenesmus. Not only is asking about the cat's current diet (type, frequency, appetite) important, but also be sure to ask questions to determine whether the patient might be dehydrated (due to decreased intake or increased water loss), may have orthopedic pain, or may be disinclined to use the litter box because of social or toileting factors (fear, unpleasant box). Click here to download a client form with specific questions to ask to address these possible concerns at length.

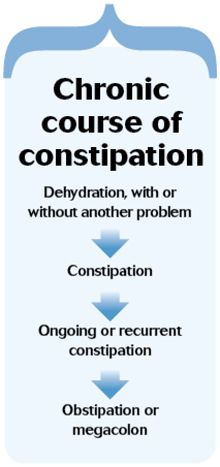

Mild constipation does not require a great deal of work-up or treatment, but identifying its causes is relevant for management to reduce the chance for progression. Chronic, recurrent constipation results in dilation of the colon and obstipation, which in some cats becomes irreversible, idiopathic megacolon that is refractory to cure due to loss of normal neuromuscular function (see the sidebar “Chronic course of constipation").1

Physical examination

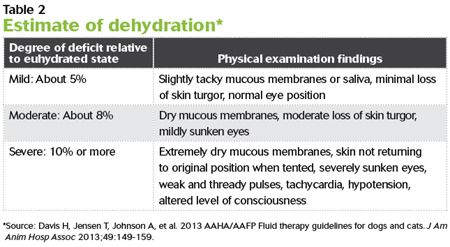

On examination, hydration is assessed by assessing skin elasticity plus coat luster, mucous membrane moisture, and eye position (Table 2). Skin elasticity can be misleading in older patients (as well as young kittens) because of age-related changes in body water distribution, elastin, and collagen. Body weight, weight change relative to previous evaluation, body condition score (indicating percentage body fat), and muscle condition score (indicating protein adequacy) help determine progression of dehydration as well as amounts needed to rehydrate the individual.

Diagnostic testing

If a cat is experiencing its first episode of uncomplicated constipation, further testing may not be needed and therapeutic rehydration will likely be adequate. For recurrent constipation or when complications such as trauma or degenerative joint disease (DJD) or neurologic signs are present, additional steps are recommended. A minimum database consisting of a complete blood count (CBC), serum chemistry profile, total thyroxine (T4) concentration measurement, and urinalysis should be performed to assess overall metabolic status and to get more information regarding the degree of dehydration.

Abdominal palpation reveals the presence of firm feces in the colon unless the feces is hidden in the pelvic rectum. Radiographs are required to confirm that the firm mass is intraluminal as well as to identify possible extraluminal problems such as obstructive masses or orthopedic or skeletal problems. Spondylosis deformans of the lumbosacral vertebral column as well as pain from degenerative changes in the shoulders, elbows, hips, stifles, or hocks may limit mobility, making it harder to get to the litter box or to squat comfortably. Evidence of pelvic fracture or other poorly aligned fractures may be observed.

Sedation may be helpful, allowing gentle manipulation of joints to assess whether range of motion is restricted or if pain is present. All cats with recurrent constipation should have a digital rectal examination. This helps to assess abnormalities of the anal glands, prostate, and pelvic inlet and the presence of rectal diverticulum, polyps, or other obstructive masses. Chronic tenesmus can result in perineal herniation.

Abdominal ultrasonography is useful to assess motility, to further examine abdominal structures, and to collect fine-needle biopsy samples of suspicious lesions. Colonoscopy may be required to biopsy mural or intraluminal masses. Computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging may be used if an intrapelvic lesion is present or if neurologic deficits are present.

Cats with evidence of neurologic problems (e.g. paraparesis, hyporeflexia, urinary retention, regurgitation) should have a complete neurologic examination to rule out sacrocaudal dysgenesis (e.g. Manx breed), spinal neoplasia, or dysautonomia.

TREATING A CONSTIPATED CAT

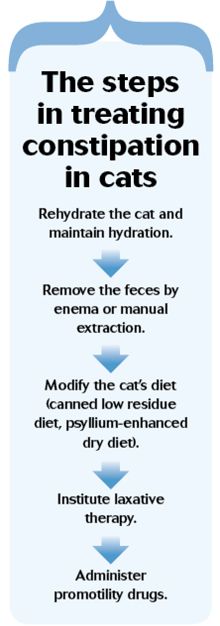

Five steps are involved in relieving constipation in cats (see the sidebar “The steps in treating constipation in cats” for an overview of the treatment process).

Step 1: Rehydration

The cornerstone of therapy for constipation is rehydration and maintenance of a hydrated state. Fluid therapy for rehydration may consist of intravenous fluids, but subcutaneous therapy is generally adequate. The volume of fluid needed to correct the fluid deficit is based on the patient's previous hydrated weight. If not known, the total protein concentration in conjunction with packed cell volume may be helpful.

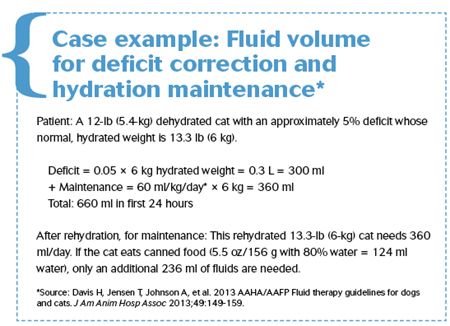

An isotonic polyionic fluid (e.g. lactated Ringer's solution) is appropriate for rehydration subcutaneously. A replacement solution such as Normosol-R (Hospira) or Plasma-Lyte 148 (Baxter) would be better choices should the intravenous route be used. A maintenance solution is preferable for ongoing maintenance therapy to prevent hypernatremia and hypokalemia, but if subcutaneous use results in discomfort, lactated Ringer's solution may be considered. The volume required for maintaining hydration is 60 ml/kg normal, hydrated weight/day (see the sidebar “Case example: Fluid volume for deficit correction and hydration maintenance”).2

Step 2: Feces removal

Removal of the feces with enemas or manual extraction may be done while the patient is being rehydrated. But do not start dietary therapy, prokinetic agents, and laxatives until the patient has been rehydrated. This is because dietary fiber and medical therapy increase fecal water or interfere with the colon's attempts to resorb water needed for cellular hydration.3

Administering smaller volumes (e.g. 35 ml) of warm water (or saline solution) mixed with 5 ml of mineral oil, glycerin, polyethylene glycol (PEG or PEG 3350), lactulose, or docusate sodium several times throughout a 24-hour period is safer and more effective than administering the entire volume as a bolus.1 Because docusate sodium increases absorption of intraluminal contents into the bloodstream, it should not be administered concurrently with mineral oil.

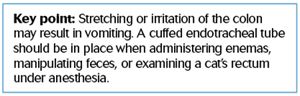

Pediatric rectal suppositories can also be used (e.g. bisacodyl, docusate sodium). If the patient is anesthetized or sedated for rectal manipulation (digital examination, manual fecal extraction, or enema administration), use a cuffed endotracheal tube to prevent aspiration from vomiting.

Step 3: Dietary therapy

Soluble fibers (e.g. pectin, oligosaccharides) are capable of adsorbing (binding) water and forming a gel. Insoluble fibers increase fecal bulk, resulting in distention and reflex contraction. Both interfere with water reabsorption into the body and should only be considered when a patient is well-hydrated. Different fiber sources have different soluble:insoluble proportions.

Fibers can also be characterized by differences in fermentability. This refers to the ability of intestinal bacteria to produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) and gas from the fiber. Moderately fermentable fibers such as beet pulp are preferable to a highly fermentable, high-gas-forming fiber source.4-6 SCFAs are vital as an energy source for colonocytes and are key in motility.

While a psyllium-enhanced dry diet has been shown to be effective in treating constipation,7 increasing water intake by including wet foods and increasing desirable water stations in the home is beneficial. As with all things in cats, individualization is critical. Regardless of which diet is chosen, reassess the patient to ensure that the diet is having the desired effect.

Step 4: Laxative administration

Cathartics are agents that increase colonic motility. They include hyperosmotic laxatives such as polysaccharides (e.g. lactulose) and PEGs or those that irritate and stimulate the mucosa (e.g. vegetable oils, sennoside, glycerin).

True laxatives act by other mechanisms. Lubricating laxatives (e.g. mineral oil, hairball remedies) impair water absorption from the colon into the body; emollient laxatives (e.g. anionic detergent such as docusate sodium) enhance absorption of lipid into the body, but impede water absorption into the body; bulk-forming laxatives (e.g. cellulose or poorly digestible polysaccharides such as cereal grain) increase fecal bulk, fermentation, and viscosity.

Step 5: Promotility drug administration

Consider promotility drugs after other therapies have been instituted and shown to be insufficient. Cholinergic agents (e.g. bethanechol) have undesirable side effects and cannot be recommended.8 Drugs affecting serotonin 5-HT4 receptors (e.g. cisapride, mosapride, prucalopride, tegaserod) have been used to effect.9-11 These should be given orally, as the transdermal route fails to deliver therapeutic levels.11 Experimentally, nizatidine and ranitidine inhibit anticholinesterase activity, acting synergistically with cisapride.12

If the patient has concurrent medical problems, it may be receiving other medications that might exacerbate constipation. These include those that increase dehydration, such as diuretics, and those that interfere with intestinal motility, such as anticholinesterase and sympathomimetic agents, barium, opioids, tricyclic antidepressants, and some H1-antihistamines.

WHAT ROLE DOES THE ENVIRONMENT PLAY?

A basic environmental need is to have multiple but separated resources.13 These include duplicates each of water, food, litter boxes or outside latrines, perches, resting areas, and toy stations. By having multiple sites, separate from each other, the chance of intercat aggression or threat (perceived or real) from other individuals is minimized. Having unhooded litter boxes is important to eliminate the risk of ambush.

Litter boxes need to be large (at least 1.5 times the length of the cat) and very clean. The litter boxes-and all resource stations-need to be easy to access, especially for a cat that is mobility-restricted (e.g. due to DJD).

Water stations must also be kept clean and freshened regularly. Feeding small amounts of food frequently results in cats drinking a greater volume of water.14 Wet food increases water intake significantly, favoring a positive hydration status.

TO CUT IS TO CURE?

Colectomy should be considered a “last resort” for a cat with megacolon that is refractory to medical management and has been struggling with obstipation for more than six months. If pelvic trauma resulting in malunion occurred more than six months earlier, colectomy is likewise justified.

Should pelvic trauma have occurred less than six months ago, however, pelvic osteotomy may be all that is required to prevent megacolon from developing in cats.

Colectomy is a procedure with significant potential complications and should be referred to a surgeon with advanced soft tissue and anastomosis skills whenever it's possible.

SUMMARY

Early correction and management of constipation will help prevent irreversible problems from developing. The effects of all drugs and dietary manipulations depend on the patient being adequately hydrated. Behavioral and environmental aspects should not be overlooked.

Clean, attractive litter boxes that are safe and easy to access not only enhance a positive quality of life but also prevent retention of feces or inappropriate elimination.

Regular follow-up is very important. Assessing the effect of the recommendations on the individual and making adjustments as warranted will provide the best outcome.

Margie Scherk, DVM, DABVP (feline practice)

catsINK

Vancouver, Canada

References

1. Washabau RJ, Hasler AH. Constipation, obstipation, and megacolon. In: August JR, ed. Consultations in feline internal medicine. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, 1997;104-112.

2. Davis H, Jensen T, Johnson A, et al. 2013 AAHA/AAFP fluid therapy guidelines for dogs and cats. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2013;49(3):149-159.

3. Davenport DJ, Remillard RL, Carroll M. Constipation/obstipation/megacolon. In: Small animal clinical nutrition. 5th ed. Topeka: Mark Morris Institute, 2010;1117-1126.

4. Chandler ML. Nutritional strategies in gastrointestinal disease. In: Washabau RJ, Day MJ, eds. Canine and feline gastroenterology. St. Louis: Saunders/Elsevier, 2013;409-415.

5. Sunvold GD, Fahey GC, Merchen NR, et al. Dietary fiber for cats: in vitro fermentation of selected fiber sources by cat fecal inoculum and in vivo utilization of diets containing selected fiber sources and their blends. J Anim Sci 1995;73(8):2329-2339.

6. Sunvold GD, Fahey GC, Merchen NR, et al. In vitro fermentation of selected fibrous substrates by dog and cat fecal inoculum: influence of diet composition on substrate organic matter disappearance and short-chain fatty acid production. J Anim Sci 1995;73(4):1110-1122.

7. Freiche V, Houston D, Weese H, et al. Uncontrolled study assessing the impact of a psyllium-enriched extruded dry diet on faecal consistency in cats with constipation. J Feline Med Surg 2011;13(12):903-911.

8. Reynolds JC. Prokinetic agents: a key in the future of gastroenterology. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 1989;18(2):437-457.

9. Briejer MR, Prins NH, Schuurkes JA. Effects of the enterokinetic prucalopride (R093877) on colonic motility in fasted dogs. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2001;13(5):465-472.

10. Washabau RJ. Large intestine. In: Washabau RJ, Day MJ, eds. Canine and feline gastroenterology. St. Louis: Saunders/Elsevier, 2013.

11. Dawn Boothe, Department of Clinical Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine, Auburn University, Auburn, Alabama: Personal communication, 2014.

12. Ueki S, Seiki M, Yoneta T, et al. Gastroprokinetic activity of nizatidine, a new H2-receptor antagonist, and its possible mechanism of action in dogs and rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1993;264(1):152-157.

13. Ellis SLH, Rodan I, Carney HC, et al. AAFP and ISFM feline environmental needs guidelines. J Feline Med Surg 2013;15(3):219-230.

14. Kirschvink N, Lhoest E, Leemans J, et al. Water intake is influenced by feeding frequency and energy allowance in cats, in Proceedings. 9th Congress ESVCN, 2005.