AVMA 2017: Managing Oral Tumors in Dogs

Early recognition and diagnosis, appropriate staging, and timely treatment elicit the best prognosis for these patients.

Early detection and prompt treatment can lead to good outcomes for dogs with oral tumors, but veterinarians need to know how to spot these lesions, according to Erin D. Vicari, VMD, DAVDC, of the Animal Emergency and Referral Center of Minnesota in Oakdale. In a lecture at the 2017 American Veterinary Medical Association Convention in Indianapolis, Indiana,

Dr. Vicari said that oraltumors make up 6% of all tumors in dogs and discussed the need for clinicians to recognize and treat these tumors promptly. “Early detection of oral tumors directly correlates with clinical prognosis for many tumor types,” she said, noting that many good treatment options are available to help clinicians manage these tumors.

Clinical Signs

To facilitate prompt diagnosis, Dr. Vicari advised clinicians to be aware of how the lesions may present. Oral tumors may be associated with many or no clinical signs, which—when they occur—may include a visible mass, swelling, facial deformity, bleeding, chewing difficulty, reduced appetite, or weight loss.

Dr. Vicari advised clinicians always to perform a thorough oral examination, as well as an extraoral one, during routine annual examinations or dental cleanings, even in the absence of a clinical problem in a dog’s oral cavity.

RELATED:

- Antihyperglycemic Effect of D-allulose in Dogs Given Oral Glucose

- Oral Capromorelin Stimulates Appetite in Dogs with Inappetence

Tumor Classification

Oral tumors are typically classified into 3 categories, Dr. Vicari said: odontogenic tumors and cysts, nonodontogenic tumors, and inflammatory or reactive lesions. She discussed common types from each category, urging clinicians to be aware of changes in the nomenclature of oral tumors.

Odontogenic Tumors and Cysts

These arise from embryologic structures associated with tooth development, Dr. Vicari said. The most common odontogenic tumor is canine acanthomatous ameloblastoma (formerly known as acanthomatous epulis). Although benign, it is locally aggressive and can invade bone. However, wide surgical excision of the tumor (with 1- to 2-cm margins where possible) is considered curative. Surgical resection is also preferred over radiation therapy, she added, because up to 20% of irradiated canine acanthomatous ameloblastomas undergo malignant transformation.

Odontoma is another benign odontogenic tumor. It has mixed mesenchymal and epithelial origins and predominantly arises in young dogs. This tumor typically is encapsulated, presents along the dental arch, and has characteristic radiographic features. According to Dr. Vicari, a compound odontoma has evidence of identifiable tooth components known as denticles throughout the mass, whereas a complex odontoma appears as an irregular mass of calcified material. Although odontomas also are locally aggressive, their early diagnosis allows for marginal surgical excision, which is considered curative.

Amyloid-producing odontogenic tumors (formerly known as calcifying epithelial odontogenic tumors) are uncommon, benign, expansive tumors that appear as gingival enlargements, Dr. Vicari said. Again, wide surgical excision is considered curative.

Peripheral odontogenic fibroma (formerly known as fibromatous and ossifying epulis) is a benign, often slow-growing tumor that arises from periodontal structures. Although surgical excision is curative, Dr. Vicari noted that extracting the involved teeth with complete excision of the associated bone and periodontal ligament tissues may also be required.

Dentigerous cysts arise from embryologic structures associated with unerupted teeth. Although benign, these lesions can expand and destroy surrounding bone and teeth. Surgical excision must include debridement and complete removal of the unerupted tooth and associated cyst lining, Dr. Vicari said. However, she emphasized that pre-vention is the best approach and recommended that clinicians extract any unerupted teeth.

Nonodontogenic Tumors

In dogs, most nonodontogenic tumors are malignant, Dr. Vicari said, and commonly include melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma, fibrosarcoma, and osteosarcoma.

Malignant melanoma is the most commonly reported oral tumor in dogs, predominantly arising in older patients. Melanoma is highly metastatic, Dr. Vicari said, so clinicians should presume that metastasis has occurred until proven otherwise. She noted that tumors smaller than 2 cm in diameter are more likely to have a better prognosis. Similarly, tumors with a low mitotic index may not have metastasized at the time of diagnosis, thus improving clinicians’ chances of gaining local control. Treatment requires wide surgical excision of the tumor, she said, and recommended referral to an oncologist for adjunctive treatment (radiation therapy, immunotherapy, vaccine, or chemotherapy).

Squamous cell carcinoma is the sec-ond most common oral tumor in dogs, Dr. Vicari said. It typically presents as an erythematous and ulcerated lesion, may arise anywhere in the oral cavity, and is locally aggressive and osteolytic.

Squamous cell carcinoma can metastasize but tends to do so later in the disease, she said, so wide surgical excision can be curative. She advised clinicians to take a biopsy sample from any unusual or unexpected lesion in the oral cavity, including from nonhealing extraction sites or regions where teeth may have fallen out unexpectedly. Treatment options include wide surgical excision with adjunctive radiation therapy.

Fibrosarcoma is the third most common tumor in dogs and occurs more frequently in older, large-breed dogs, Dr. Vicari said. Fibrosarcomas in the oral cavity typically are histologically low grade but biologically high grade, with metastasis occurring in about 20% of cases. Because of the tumors’ aggressive biological behavior, Dr. Vicari advised clinicians that wide surgical excision is needed.

When osteosarcoma occurs orally in dogs, it arises more frequently in the mandible than in the maxilla, Dr. Vicari said. However, in general, compared with osteosarcoma in the appendicular skeleton, osteosarcoma in the oral cavity is less common, has a lower metastatic potential, and thus carries a better prognosis with wide surgical excision.Inflammatory or Reactive Lesions

Common inflammatory or reactive lesions that may arise in the canine oral cavity include gingival hyperplasia, focal fibrous hyperplasia, pyogenic granuloma, peripheral giant cell granuloma, and reactive exostosis, Dr. Vicari said.

She advised clinicians not to be misled by the term “epulis.” Although it has traditionally been used to describe non-neoplastic gingival enlargements, it refers to any gingival growth. It has no specific histopathologic features or biological behavior, so it could be used to describe any gingival tumor, benign or malignant, she said.

Tumor Evaluation

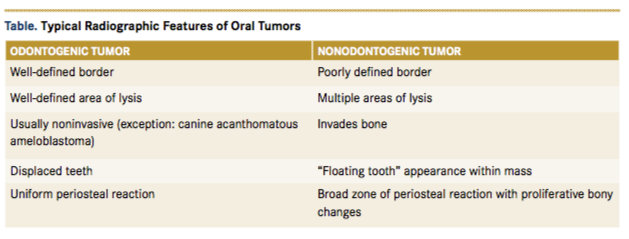

Before proceeding with anesthesia and surgery, clinicians should perform bloodwork on any dog presenting with an oral mass, Dr. Vicari said. They should conduct a thorough oral examination, including of the sublingual tissues. They should photograph oral masses, record their measurements (using the imprinted ruler on scalpel handles and periodontal probes for example), and perform complete intra-oral dental radiography. According to Dr. Vicari, recognizing some of the common radiographic features associated with odontogenic versus nonodontogenic tumors (Table) can help clinicians diagnose these lesions.

Advanced imaging techniques may also be useful, she noted. For example, computed tomography provides more detailed information about lesions and can be especially helpful when dealing with masses involving the maxilla, as well as with those located more caudally in the oral cavity.

A representative biopsy sample is also critical to diagnose any oral mass, she said. She advised clinicians to take samples from within the margins of a mass to avoid seeding tumor cells into normal tissue and inadvertently expanding the tumor margins. It is also important to avoid crossing tissue planes, she said. She advised clinicians to take deep samples from the mass to avoid hyperplastic tissue and avoid sampling any necrotic tissue. “Know your pathologist,” she added, stressing the importance of finding a reliable pathologist with experience evaluating oral tumors. Dr. Vicari emphasized the importance of correlating histopathologic features of a mass with clinical and radiographic findings.

Dr. Vicari discussed the value of taking fine-needle aspirate samples of regional lymph nodes for cytologic evaluation for tumor staging. However, she reminded clinicians that although the mandibular lymph nodes are the most accessible, only about half of oral tumors with metastasis involve them.1 Imaging examinations of the chest and abdomen are also useful in staging oral tumors, she said.

Conclusion

Dr. Vicari noted that surgical resection with 1- to 2-cm margins is the goal for most oral tumors but stated that if this is not feasible, surgical debulking may improve quality of life. Consulting an oncologist is also beneficial, she said, and adjunctive treatments may include radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and/or immunotherapy. “Treat early or refer,” she concluded. “Lots of good treatment options are available for oral tumors in dogs.”

Reference:

- Herring ES, Smith MM, Robertson JL. Lymph node staging of oral and maxillofacial neoplasms in 31 dogs and cats. J Vet Dent. 2002;19(3):122-126. doi: 10.1177/08987564020190030