Canine liver enzymes-so many questions!

Does the alphabet soup of liver enzyme activities got you stumped? Dr. Jonathan Lidbury answers common questions on interpreting canine liver laboratory results and gives guidance on how to proceed with confirming a diagnosis, including when to perform a liver biopsy.

ALT, easy as 123 ... or maybe not! (Photo: Shutterstock.com)As you all too readily know, increased serum liver enzyme activities are common in dogs and are, quite often, a diagnostic challenge. In a recent Fetch dvm360 session, Jonathan Lidbury, BVMS, MRCVS, PhD, DACVIM, DECVIM, said “Increased liver enzymes are a big cause of consternation and confusion among all of us. We have to deal with them all of the time. They're one of the most common laboratory abnormalities of all.”

Sometimes increased serum liver enzyme activities occur because the patient does have primary hepatobiliary disease, but sometimes they are secondary to extrahepatic disease. And to confound results even more, tissues other than the liver also produce these enzymes. The liver plays a major role in the metabolism and excretion of drugs and exogenous and endogenous toxins, so it's susceptible to injury from toxins and from diseases in other parts of the body. Plus, increased liver enzyme activities can occur from benign processes (e.g. hepatic nodular hyperplasia) or from conditions that are progressive and require early intervention for the best outcome (e.g. chronic hepatitis).

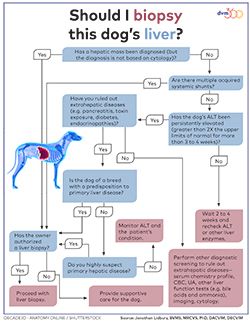

Performing extensive diagnostic evaluation, including liver biopsy, is costly and clients may be either reluctant or unable to proceed. It can be difficult to know how aggressively to work up these dogs. Dr. Lidbury says that if the cause of the elevated activity is a primary liver disease like chronic hepatitis or a liver tumor, the workup can escalate up to the need to perform a liver biopsy fairly quickly. Contrast that with extrahepatic causes. “Sometimes, especially for mild elevations in alkaline phosphatase (ALP), benign neglect may be the best course of action,” he says.

Through a logical, step-by-step approach, you can assess which dogs should be investigated for extrahepatic disease, which cases may need a liver biopsy, and which cases can be managed less aggressively.

Should I be checking ALT? AST? ALP? GGT?

Yes … but you should also know the enzymology behind all of these markers-where and why they're produced-so you know how to interpret the laboratory results. “There are two big categories,” says Dr. Lidbury. “First, we have markers of hepatocellular damage. That would include alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST). And then we have markers of cholestasis, ALP and gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT).”

ALT

ALT is found primarily in the cytosol of hepatocytes. It's released with increased cell membrane permeability or cell death. “Of all the liver enzymes, ALT is the most liver-specific,” says Dr. Lidbury. On rare occasions, ALT activity can be increased in patients with severe muscle injury. But, in general, ALT is considered a sensitive and specific marker of liver injury. “When hepatocytes die, then you get leakage,” Dr. Lidbury says. “ALT can also leak when you have just cell membrane damage. You don't have to have necrosis for ALT to go up. Also, severe ALT increases don't necessarily mean you have irreversible disease. Sometimes we misinterpret really high ALTs as irreversible disease and a poor prognosis. If you have a dog with acute liver injury, it might have a sky-high ALT, but if you can support the dog through that initial injury, then the disease could be reversible, and the liver can get back to normal. The liver has such great regenerative capacity.”

AST

In dogs, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) is found in both the mitochondria and cytosol of hepatocytes. (In human hepatocytes, AST is mainly found in the mitochondria, and so, in people, it is a marker of severe liver damage.) The cytosolic fraction is released with increased cell membrane permeability or cell death, whereas the mitochondrial fraction is released only when there is hepatocyte necrosis. In general, increases in AST parallel those in ALT, but muscle disease can increase serum AST activity. Because of this, AST is considered to be less liver-specific than ALT. “At Texas A&M, we have actually taken AST off our basic chemistry panel because we feel it doesn't add much information,” says Dr. Lidbury. A lot of the bigger reference labs still have it on their panels. It's not un-useful; it usually just parallels the ALT.”

ALP

“So next we have that problem child-the ALP,” says Dr. Lidbury. “This is probably the least liver-specific and also the most commonly elevated liver enzyme. That is why it causes problems.” As you probably remember from pathophysiology units in veterinary school, there are different forms of ALP-hepatic, bone, renal, intestinal and steroid-induced ALP isoenzymes. They all may contribute to serum ALP activity in dogs. Dr. Lidbury says, however, “Luckily, when we measure ALP, we don't have to worry about all of the isoforms because some of them aren't actually measured by the assay. They have a trivial contribution to the overall activity of ALP in the serum, which is what the assay measures.” In the liver, ALP is bound to the membranes of the hepatocytes that form the bile canaliculi and the sinusoidal membranes. In cholestasis, the membrane-bound ALP is released into circulation and the synthesis of this enzyme is induced. ALP is considered a sensitive marker of cholestasis in dogs, but because of the other isoenzymes, ALP is not liver-specific.

“I don't tend to take ALP quite as seriously as increases in ALT,” Dr. Lidbury says. “Sometimes they're not actually that clinically significant, if they're mild and the dog doesn't have other signs going on. Sometimes this is a case where benign neglect may be the best course of action, but not always. Obviously, if ALP didn't tell us anything, we wouldn't measure it. There is a nuance; it depends on looking at the whole case.”

So, what can cause increased ALP activity? Dr. Lidbury answers, “If you look in textbooks, there's a long list with about 30 to 40 reasons. But in terms of big categories, causes of increased ALP can be hepatic disease such as nodular hyperplasia (a very common, completely benign cause of increased ALP in older dogs), vacuolar hepatopathy (common with Cushing's disease), toxins, chronic hepatitis, neoplasia, biliary tract disease (such as a gallbladder mucocele) and extrahepatic disease (such as pancreatitis).”

Serum ALP activities can be increased when there is increased osteoblast activity, such as in growing dogs, or when the dog has an osteolytic disease, such as osteosarcoma. The steroid-induced ALP isoenzyme can be induced by both exogenous and endogenous glucocorticoids. Dr. Lidbury warns, “Steroid-induced isoenzyme is really important because it can be iatrogenic. Asking the owner whether the dog is on any steroids or whether they're using any steroid hand creams themselves, that kind of thing, is very important.”

GGT

Gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT) is bound to the hepatocytes in the bile canaliculi and bile ducts. Increases in serum GGT activity generally parallel those in ALP. Both GGT and ALP are considered sensitive markers of cholestasis. Dr. Lidbury says, however, “GGT can't differentiate between intrahepatic and extrahepatic cholestasis. You'd think since it's a bit further down the biliary tract, that it might. But, unfortunately, it doesn't do that.” In general, increases in GGT are considered to be less sensitive but more specific for the presence of hepatobiliary disease than those of ALP.

The pattern of liver enzymes

Dr. Lidbury confirms that looking at patterns of liver enzymes can be useful (Table 1). “For example, if you have a dog where your ALP is 10X the upper limits of normal and your ALT is increased to twice the upper limits of normal, we'd say that dog has a cholestatic pattern,” he says. “So, we'd be thinking about diseases that cause intra- or extra-hepatic cholestasis. If you have the opposite situation, and a dog has an ALT that is 10X the upper limits of normal and the ALP is only very modestly increased, then that's more of a hepatocellular damage pattern. That makes you think of things like chronic hepatitis or toxins. Sometimes you get genuinely mixed patterns, and you can't differentiate the two. But you can often get some clues.”

Table 1: Typical patterns of clinicopathological changes associated with liver disease in dogs

Laboratory test

Acute hepatitis/hepatic necrosis

Chronic hepatitis

Cirrhosis

Congenital portosystemic shunt

Biliary tract obstruction

Non-obstructive biliary tract disease

Hepatic neoplasia

ALT

^^ - ^^^

^ - ^^^

N - ^^

N - ^

N - ^^

N - ^^

N - ^^

ALP

^ - ^^

^ - ^^

N - ^^

N - ^

^^^

^ - ^^^

N - ^^

Total bilirubin

N - ^^^

N - ^^

N - ^^^

N

^^ - ^^^

N

N - ^

Preprandial SBA

N - ^^

N - ^^

^ - ^^^

N - ^^

^^ - ^^^

N

N - ^

Postprandial SBA

N - ^^

N - ^^

^ - ^^^

^^ - ^^^

^^ - ^^^

N

N - ^

Ammonia

N - ^^

N - ^^

N - ^^

^ - ^^^

N

N

N - ^

Key

ALT-serum alanine transaminase activity

ALP-serum alkaline phosphatase activity

SBA-serum bile acid concentration

N-within the reference interval

^-mild increase

^^-moderate increase

^^^-severe increase

What can the patient history and exam tell me?

Since there are so many causes of increased liver enzyme activities, Dr. Lidbury says the key is to narrow the list of all possible causes down to those that are probable for a patient on that day. The patient history and physical examination are often helpful in doing this. The patient's signalment can help refine the differential diagnosis list. See Table 2 for known age and breed predispositions for certain liver conditions.

Table 2. Signalment to refine the differential diagnosis list for hepatic injury

Age

Very young dogs are more likely to suffer from congenital conditions (e.g. congenital portosystemic shunts) or infectious diseases (e.g. infectious hepatitis), rather than neoplasia or inflammatory conditions, such as chronic hepatitis.

Copper-associated chronic hepatitis

Bedlington terriers

Skye terriers

West Highland white terriers

Dalmatians

Labrador retrievers

Idiopathic chronic hepatitis

Doberman pinchers

Cocker spaniels

Congenital portosystemic shunts

Maltese terriers

Yorkshire terriers

Havanese terriers

Pugs

Miniature schnauzers

When taking a patient's history, be sure to ask the client specifically about exposure to hepatotoxins such as cycads (including the sago palm), blue green algae, Amanita mushrooms, aflatoxins, heavy metals, xylitol or chlorinated compounds. Drugs that can be hepatotoxic include ketoconazole, azathioprine, carprofen, lomustine, acetaminophen, mitotane, phenobarbital and various antimicrobial agents.

“Asking specifically about nutraceutical and herbal remedies is important, especially in this situation, because there are quite a few herbal remedies that are known to have the potential to cause liver injury in dogs,” Dr. Lidbury says. Those include herbal teas, pennyroyal oil and comfrey.

Checking the dog's vaccination history is also important because leptospirosis and canine adenovirus-1 can cause hepatic injury.

Early in the course of liver disease, a dog may not have any or nonspecific findings or clinical signs such as vomiting, diarrhea, weight loss, polyuria/polydipsia and hyporexia. Dr. Lidbury admits that these are not very helpful signs since so many different diseases can cause them. “But certainly, if you have a dog with increased liver enzymes and that kind of clinical sign, then that may make you a little more aggressive about how you approach that dog,” he says. He says it's also important to remember that dogs with hepatobiliary disease don't always display clinical signs or have abnormal physical examination findings.

Certain exam findings suggest an extrahepatic disease is causing increased liver enzyme activities. For example, polyphagia is consistent with diabetes mellitus or hyperadrenocorticism and bilateral symmetric alopecia is consistent with hypothyroidism or hyperadrenocorticism. Physical examination findings consistent with hepatobiliary disease include icterus, ascites, poor body condition, stunted growth, hepatomegaly or signs of hepatic encephalopathy. When any of these clinical signs are present, you will want to investigate further.

What clues can other lab tests provide?

Other changes on a serum chemistry profile can provide clues about the cause of increased serum liver enzyme activities. “You can look for signs of liver dysfunction,” Dr. Lidbury says. “Things the liver produces-albumin, cholesterol, glucose, and blood urea nitrogen (BUN)-can be decreased with liver disease or decreased hepatic function. And bilirubin can be increased.”

Dr. Lidbury warns, “It's definitely possible to have serious liver disease and have all of those things completely normal. The liver has this large reserve capacity. That's a really good thing for the body, but it makes our life a bit harder when we're trying to diagnose liver disease.” It's important to remember that these changes are not specific for hepatobiliary disease. For example, the serum bilirubin concentration may also be increased when there is hemolysis.

Dr. Lidbury offers this helpful tip: “When we look at a chemistry panel, especially when we're in a rush on a busy day in the clinic, we tend to look for things that are flagged. You go down the list of 10 to 15 analytes and look for things that are high or low. You can miss things doing that. Some of these numbers are in the normal range, but at the low end of normal. If several things are like that, it can give you an impression that the liver is not working so well. So, try to slow yourself down and actually look at the numbers. Really read them.”

Patterns of serum liver enzyme activities can suggest certain pathologies. For example, during cholestasis, ALP activity is dramatically increased and is higher than ALT activity. There may also be evidence of extrahepatic diseases. A complete blood count (CBC) can suggest inflammatory disease or rule out hemolysis. If the CBC shows microcytosis, that's consistent with portosystemic shunting (or iron deficiency).

Dr. Lidbury also recommends conducting a urinalysis (UA). “Usually you can justify doing a UA whenever doing a chemistry panel. It just allows you to fully interpret that chemistry panel.” He notes that urine specific gravity can be decreased in patients with hepatic insufficiency or portosystemic shunts. Excessive bilirubinuria in dogs implies hemolytic or hepatobiliary disease. Urate urolithiasis seems to be more common in patients with portosystemic shunts than those with other types of hepatic dysfunction, but urate crystalluria is not specific for hepatobiliary disease.

When should I do more testing?

Once you have completed a basic evaluation of a dog, you have to decide whether to pursue further diagnostic testing. “It's hard to make hard and fast rules about when you should take things further. Every case is different,” says Dr. Lidbury. “So what I offer are more guidelines than rules.”

Dr. Lidbury's guidelines:

If clinical findings or other laboratory test results suggest primary hepatobiliary disease, pursue further diagnostic testing.

If clinical findings or laboratory test results suggest extrahepatic diseases are the cause of increased liver enzyme activities, further diagnostic evaluation to identify the underlying disease is needed.

If serum liver enzyme activities (ALP or ALT) are severely (three times the upper limit of the reference range) or persistently increased (greater than twice the upper limit of the reference range for more than three to four weeks), further diagnostic evaluation is needed.

Because ALT is more liver-specific than ALP, increases in serum ALT activity are more concerning or worrisome than increases in ALP.

If none of these conditions apply, then it is reasonable to wait and recheck the serum liver enzymes later.

What comes after a chemistry panel, CBC and UA?

Dr. Lidbury's advice: “Next we may want to do some bile acid tests. Ammonia has some utility, but it's more limited and not every practice has the capability to measure ammonia. It seems to be affected a bit more by other variables, too.” He says that measurement of plasma ammonia and paired preprandial/postprandial bile acids are sensitive tests for portosystemic shunting, and he recommends performing one of these tests when a portosystemic shunt is suspected. Because of the hepatic functional reserve capacity, these tests are not as sensitive in detecting hepatic insufficiency (in the absence of shunting). “Remember that dogs can have these normal liver function tests and still have significant liver disease,” Dr. Lidbury says. Also, performing these tests does not always change the decision about whether to perform a liver biopsy.

Imaging

Radiography. “Plain radiographs are useful for things like assessing the general size and shape of the liver,” says Dr. Lidbury. “You can perhaps see masses or maybe extrahepatic disease, like a foreign body in the GI tract. But radiographs rarely lead to a definitive diagnosis of liver disease.”

Abdominal ultrasonography. This form of imaging is more useful than radiography for evaluating the hepatic parenchyma and the biliary tract. “The biliary tract is quite a hard area to image. Sometimes you'll get a definitive diagnosis, like a gallbladder with a typical ‘sliced kiwi fruit' appearance of a gallbladder mucocele,” says Dr. Lidbury. “But sometimes ultrasound doesn't give us a definitive diagnosis. We may see nonspecific changes like an enlarged liver or a small liver with a slightly abnormal echo texture. You may also have a very boring, completely normal ultrasound and still have chronic hepatitis going on. A normal ultrasound doesn't rule out severe liver disease. That's important to bear in mind.” Unless a disease leads to architectural changes in the hepatobiliary system, a definitive diagnosis can't be made with ultrasonography. Despite this limitation, Dr. Lidbury says that when primary hepatic disease is suspected, abdominal ultrasonography is usually performed before liver biopsy.

Scintigraphy. Dr. Lidbury says scintigraphy is being used less frequently-they rarely use the technique at Texas A&M. “It involves injecting a radioactive isotope, which is why people didn't like to do it. It's a very good test for portosystemic shunting. But it doesn't tell you whether the shunt is intrahepatic or extrahepatic.”

CT and MRI. Dr. Lidbury says that cross-sectional imaging is being used more often for assessing abdominal disease in dogs. Computed tomography (CT) is used most often because it's quick and a bit cheaper than magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). “Obviously not everybody is going to be able to do this at the moment. But who knows? Maybe in 20 years, every practice will have a micro-CT scanner rather than an x-ray unit,” ponders Dr. Lidbury. “It's a nice way to look for congenital portosystemic shunts. And it's quite good if you've got a big liver mass. Surgeons like to look at these CTs before they decide if they will try to resect a mass or not.”

Cytology

“Cytology-this can definitely be useful. But I don't do it in every case,” says Dr. Lidbury. “I pick my cases. It's relatively easy to do. You just need ultrasound guidance. It's pretty safe and quite cheap, too.” Hepatic cytology can lead to a definitive diagnosis of certain diseases, such as lymphoma, and can be highly suggestive for the presence of others. You may wish to perform cytology when you suspect a round cell tumor is present, when you suspect infectious agents (e.g. Histoplasma capsulatum) and when hepatic masses are visible with ultrasonography. “Cytology allows us to look at the cells, but it doesn't allow us to see how those cells are actually arranged in their architecture. Because of that, there are some conditions-like chronic hepatitis-that you can't diagnose cytologically.”

When should I biopsy the liver?

To make a definitive diagnosis of primary hepatic disease, a liver biopsy is often required. “This is kind of the last step in the diagnostic workup,” says Dr. Lidbury. “It's quite an invasive and expensive technique.” Click here (or on the image) to download a flowchart showing how Dr. Lidbury suggests approaching the decision about whether to perform a liver biopsy on a particular patient.

Before doing a biopsy, Dr. Lidbury recommends assessing the dog's risk of hemorrhage by measuring prothrombin and activated partial thromboplastin time, ideally measuring serum fibrinogen concentration, and performing a platelet count. He also usually does a buccal mucosal bleeding time.

The three types of liver biopsy techniques in dogs are percutaneous needle biopsy, laparoscopic biopsy and surgical biopsy. Each technique has advantages and disadvantages. See Table 3 for a comparison of the three techniques. Dr. Lidbury says, “All of them are valid ways to get liver biopsies. It just depends on what you have available and how comfortable you feel. Sometimes it's a bit about the patient, too.”

Table 3. A comparison of liver biopsy techniques

Percutaneous needle biopsy

Laparoscopic biopsy

Surgical biopsy

Invasiveness

Least

Intermediate

Most

Expense

Least ($)

Intermediate ($$)

Most ($$$)

Size of biopsy specimen

Smallest

Intermediate

Largest

Hospitalization or postoperative care required?

No hospitalization required

Patient is usually discharged same day

Patient may need to be hospitalized; incision requires postoperative care

Bleeding risk

Highest

Low

Low

Ability to control hemorrhage

Least ability to control; if bleeding occurs, may need to perform exploratory surgery to control

Can apply pressure or gel foam to area of hemorrhage through laparoscopic incisions

Direct visualization allows surgeon to control bleeding

Other disadvantages?

Special equipment required, which translates to increased cost for client

Other advantages?

Visualization of liver and surrounding area is best of three techniques; simple procedure to perform

No matter which technique is chosen, it's important to collect multiple biopsy samples. Dr. Lidbury advises, “I'd keep part of the biopsy specimens back for aerobic and anaerobic culture and copper quantification. When you get the pathology report back and it says there are bacteria, or they suspect it's copper, you're going to regret it if you have thrown everything into formalin.”

“Again, it is hard to make universal rules about when to perform a liver biopsy, because every case is different,” he says. But when you suspect primary hepatic disease, he advises that it's better to go ahead and do the biopsy rather than delay until the dog is in end-stage liver failure, at which point treatment will probably be ineffective.

Suggested reading

> Alvarez L, Whittemore J. Liver enzyme elevations in dogs: diagnostic approach. Compend Contin Educ Vet 2009;31(9):416-418.

> Cooper J, Webster CL. The diagnostic approach to asymptomatic dogs with elevated liver enzyme activities. Vet Med 2006:101(5):279-284.

> Lidbury JA, Steiner JM. Diagnostic evaluation of the liver. In: Canine & feline gastroenterology. 1st ed. St. Louis: Elsevier Saunders, 2013;863-875.

About the speaker: Jonathan Lidbury, BVMS, MRCVS, PhD, DACVIM, DECVIM, is an assistant professor in the Department of Veterinary Small Animal Clinical Sciences at Texas A&M University in College Station, Texas. He is interested in all areas of small animal gastroenterology and is working to develop new noninvasive tests for liver disease in dogs.