Canine Urinary Incontinence

The mechanisms behind this familiar condition are multilayered and poorly understood, and treatment must be individualized based on the cause of the problem.

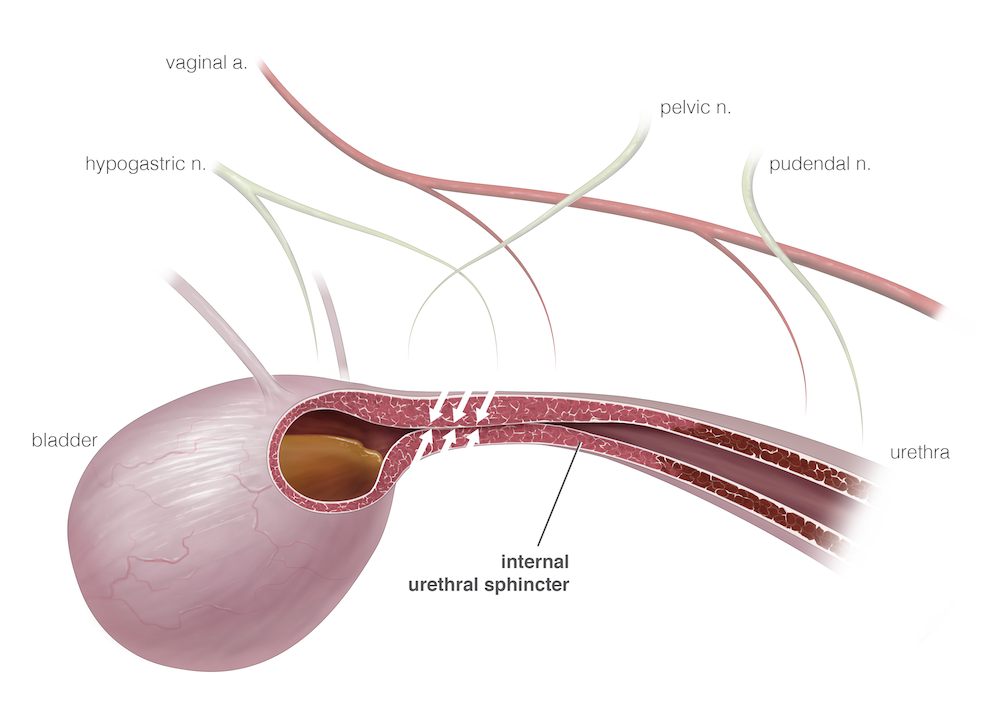

Illustration by Diogo Guerra, medical illustrator

Urinary incontinence (UI), a common problem encountered in small animal practice, can result from congenital anatomic abnormalities, urine retention and overflow incontinence, or sphincter incompetence. The timing of the onset of UI and the ability of a dog to empty its bladder are important in determining the underlying cause. Behavioral changes are important factors as well.

This review focuses on 2 of the most common causes of UI: urethral sphincter mechanism incompetence (USMI) and functional urethral obstruction, also known as detrusor urethral dyssynergia (DUD).

History and Diagnosis

A careful history is essential when discussing UI with pet owners. UI must be distinguished from behavioral conditions and systemic problems (eg, polyuria, pollakiuria), and it is important to establish that the animal is unaware of the passage of urine. Young dogs that have never been continent or have been “difficult to housetrain” should be evaluated for congenital abnormalities, such as ectopic ureter(s). Patients whose UI has developed concurrent with an increase in water intake should be evaluated for disorders causing polyuria and polydipsia.

RELATED:

- Spaying Large-Breed Dogs Later in Their First Year May Decrease Incontinence Risk

- Recognizing Urinary Incontinence in Aging Pets

Physical examination should include a rectal examination with careful palpation of the urethra. Obstructive processes such as urethral neoplasia and prostatic hyperplasia can often be diagnosed this way. If possible, observe the dog while it is urinating. This is particularly important in males because functional obstruction and overflow incontinence may be more common than previously thought. Residual urine volume should be measured after voiding in dogs that have a narrow urine stream, exhibit stranguria, or only drip urine. Finally, a neurologic and orthopedic evaluation should be conducted if the dog is unable to posture normally to urinate, as this can lead to incomplete emptying of the bladder and UI.

Urinalysis with sediment examination should be conducted for all patients with UI. Although urine leakage may be exacerbated by a urinary tract infection (UTI), the incontinence itself may predispose the patient to a UTI. There is debate as to whether treating dogs with bacteriuria that lack signs, such as stranguria or dysuria, is appropriate. Bloodwork is indicated if the patient has a low urine-specific gravity, particularly in the face of dehydration.

UI typically develops in young or middle-aged dogs.1 Those with older onset may require additional diagnostic investigation as to an underlying cause. Some dogs may have mild USMI but are rarely incontinent until a secondary factor, such as increased urine volume, comes into play. If the underlying reason for polyuria can be addressed, the UI may improve.

Urethral Sphincter Mechanism Incompetence

USMI is the most common cause of UI in dogs, affecting up to 20% of all neutered females and 30% of neutered females weighing over 20 kg.2,3 It is less commonly reported in neutered males and intact dogs of both sexes. In most dogs, incontinence occurs within 3 to 4 years of neutering,1 although it may not become a major problem until later in life when it can be complicated by diseases that cause polyuria and polydipsia. Among the most commonly affected breeds are the Old English sheepdog, Doberman pinscher, boxer, German shepherd, and Weimeraner.3 Results from a recent study indicate that earlier neutering may increase the risk of USMI development in dogs with a projected adult body weight greater than 15 kg.1

Pathophysiology

Although many risk factors for the development of UI in dogs have been identified, the mechanism of development remains unclear. The underlying mechanism is likely multifactorial and involves the pituitary-gonadal axis, the anatomic structure of the lower urinary tract, and the integrity and tissue characteristics of the lower urinary tract’s supporting structures. Several things are important in the maintenance of a closed urethra, including vascular tone (which can represent up to 30% of closure pressure), the strength of supporting structures in the pelvic region, and the position of the bladder. Some studies’ findings have implicated a rise in luteinizing hormone and gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) levels as well as increases in their receptors in female animals secondary to the decline in estrogen levels after neutering.4,5 These changes may affect smooth muscle contractility in the lower urinary tract. In support of this theory, data from one study have shown that the administration of GnRH analogues to dogs with USMI can lead to improvement of continence.5

In animal models, estrogen has trophic effects on the vasculature and tissue matrix of the lower urinary tract and its support structures. The decline in estrogen levels after neutering in female dogs may cause a decrease in the vasculature of the urethra and its supporting tissues, which is an important part of maintaining a closed urethra. There is also a possibility that the collagen content may be altered in females with USMI; however, further studies are needed. Another important factor in maintaining continence is bladder position. In healthy dogs, intra-abdominal pressure transmits to the bladder and proximal urethra. This equalizes the pressure between the bladder and its outflow tract, preventing leakage. In dogs with a caudally positioned bladder (pelvic bladder), the pressure increases that occur with movement, barking, and coughing transmit to the bladder, not the urethra, thus creating a pressure gradient from the bladder to the urethra and resulting in leakage. This may be more common in breeds such as greyhounds, Doberman pinschers, and Weimeraners.6

The postneuter alteration to the urethral sphincter mechanism that is most often a therapeutic target in female dogs is the reduction in number and sensitivity of adrenergic α-receptors. Stimulation of these receptors leads to an increase in contraction of the urethral smooth muscle or “internal” urethral sphincter. Increasing the number of receptors with estrogen supplementation or increasing stimulation with α-agonists is the most common medical therapy for acquired UI in dogs.

In women, UI is often caused by detrusor hyperreflexia, or overactive bladder. This condition occurs when the bladder spontaneously contracts without reaching full capacity, resulting in the leakage of urine. This condition is treated with antimuscarinic drugs such as oxybutynin and imiprimine. Some studies have suggested that this condition may occur in dogs with UI7,8; however, the definitive diagnosis relies on urodynamic testing. In lieu of this, some practitioners place patients on these medications if they fail to respond to α-agonist and estrogen therapy.

Treatment

In most USMI cases, otherwise healthy patients are treated initially with either α-agonist medications, such as phenylpropanolamine (Proin, PRN Pharmacal), or estrogen compounds, such as diethylstilbestrol or estriol (Incurin, MSD Animal Health). α-Agonists increase stimulation of the adrenergic receptors on the internal urethral sphincter, whereas estrogens may upregulate the expression of such receptors. There is anecdotal evidence that the 2 drugs in combination may be synergistic and benefit patients that do not respond to either drug alone. At The Ohio State University Veterinary Medical Center, we recommend obtaining baseline systolic blood pressure before starting phenylpropanolamine, because hypertension is a potential adverse effect (AE) of α-agonist therapy. The dog should also have its blood pressure monitored after 2 to 4 weeks on the medication. Other AEs of phenylpropanolamine include restlessness, aggression, decreased appetite, and insomnia. AEs of estrogen therapy include mammary and vulvar swelling and attractiveness to male dogs. These effects generally resolve when the medication dose is decreased or stopped.

Dogs that do not respond to appropriate medical therapy should be evaluated for other lower urinary tract disease via imaging, including abdominal ultrasound and/or contrast radiography. We routinely perform cystoscopy in patients with medically unresponsive UI to rule out anatomic abnormalities that may be contributing to clinical signs. In some cases, urodynamic evaluation can be performed at specialized centers to rule out overactive bladder and confirm the diagnosis of USMI.

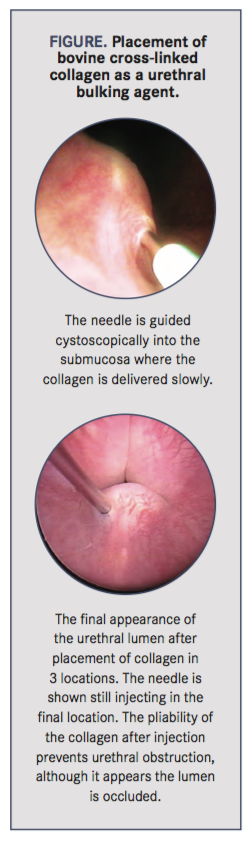

Patients that cannot tolerate or do not respond to medical therapy may be candidates for surgical intervention. The most commonly practiced procedures in the United States are urethral collagen injections and placement of an artificial urethral sphincter. Both procedures have pros and cons, and careful patient selection is necessary for an optimal outcome.

The artificial urethral sphincter is a silicone cuff that is placed around the urethra. It is attached to a subcutaneous port with an injection membrane. Fluid inside the cuff can be adjusted by the veterinarian to achieve a level of pressure that maintains continence during bladder filling but does not lead to obstruction when the bladder and abdomen contract. In a review of 27 cases treated with an artificial urethral sphincter, all had significantly improved continence, with only 2 dogs having complications involving partial urethral obstruction.9

Injectable urethral bulking agents have been used, particularly bovine cross-linked collagen, to increase resting urethral pressure in dogs with UI. The material is injected submucosally into the proximal urethra via cystoscopy (Figure). Although many materials have been investigated, the theory behind all injectable bulking agents is to increase the stretch in the sphincter muscle fibers, leading to increased resting closure pressure in the urethra. In addition, the implant may narrow the diameter of the urethral lumen, allowing the urethral sphincter to close more effectively. Based on results from 2 long-term reviews, postprocedure continence in female dogs with UI was 66% to 68%; of those that were not continent, 46% to 60% achieved continence with the addition of medical therapy.10,11 Injectable bulking agents have also been used with success in male dogs and in patients that were incontinent after ectopic ureter correction.10,11 The largest drawback of this procedure is the variability in duration of effect. The median duration of continence without additional medical therapy ranged from 8 months to 2 years.11

Other surgical therapies for UI focus on increasing the transmission of intra-abdominal pressure to the proximal urethra and improving stability and pressure within the urethra. Colposuspension, which attaches the uterine remnant to the pelvic ligament and thus draws the bladder neck and proximal urethra farther into the abdomen, has been found to have variable success and a high failure rate due to breakdown of the attachment to the pelvic ligament.12

Male dogs with UI pose a more difficult challenge. Less than 50% of male dogs respond to medical therapy, and the most successful treatment is phenylpropanolamine.13 There is some evidence that testosterone cypionate may provide some improvement.14 Alternative treatment in males that fail medical therapy include surgical placement of an artificial urethral sphincter and urethral collagen injections, which may be performed antegrade through a cystotomy incision or retrograde via perineal urethrotomy.

Functional Urethral Obstruction

The poor response of male dogs with UI to traditional USMI therapy may be due to misdiagnosis. It is likely that many of these dogs have overflow incontinence secondary to an inability to empty the bladder rather than a weak urethral sphincter. The etiology of functional obstruction or DUD is elusive and may involve the reticulospinal tract. The net effect is incoordination between the reflexive relaxation of the urethral smooth and skeletal muscle when the bladder contracts. It appears that the obstruction can involve either the smooth or skeletal muscle of the urethra or a combination.

The diagnosis is made by assessing urine stream and residual urine volume. Otherwise healthy dogs should have less than 1 to 2 mL/kg of urine in the bladder after a normal void. Some dogs with DUD, however, will have more than 15 mL/kg. Other causes of obstruction, such as strictures, uroliths, and extramural compressive lesions, must be ruled out before a diagnosis of DUD can be made. This can be accomplished easily with contrast cystourethrography, which may also assist in guiding therapy because the location of the most resistance usually sits just distal to an abnormally wide portion of the urethra.

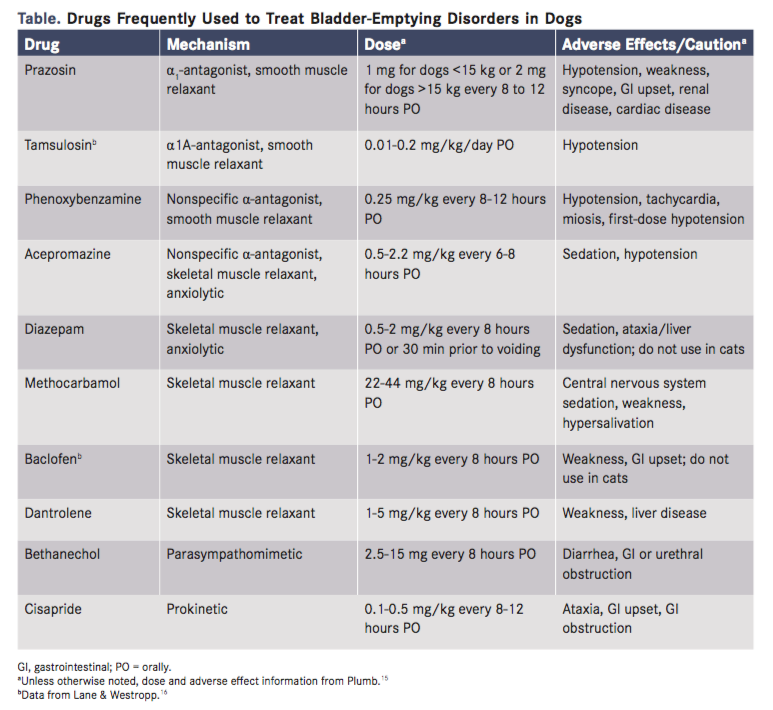

Medical treatment for DUD generally consists of muscle relaxation and, occasionally, anxiolytic therapy (Table). The prostatic urethra contains primarily smooth muscle, and the penile urethra contains primarily skeletal muscle. The perineal urethra has the 2 types. It is often necessary to use both smooth and skeletal muscle relaxants in these patients to achieve the desired result. α-Antagonists are a mainstay of smooth muscle relaxation, while the addition of low doses of diazepam just before urination can relax the skeletal muscles. Some dogs exhibit worsening clinical signs when stressed or anxious, and these patients may benefit from trazadone, fluoxetine, or other anxiolytic medication. Clients should be instructed on indications for and technique of urethral catheterization in their male dog. This can prevent costly emergency visits and provide the dog with temporary relief.

Little is known about long-term outcomes in male dogs with DUD, and evidence for treatment efficacy is lacking. Some patients may require significant dose adjustments of medications to determine the optimal therapy. Dogs that do not respond to treatment may require urethral stenting—although this is considered a salvage procedure and may lead to significant AEs.

Conclusion

The mechanisms behind UI in dogs are multilayered and poorly understood. Treatment must be tailored based on whether the problem involves an inability to hold urine during bladder filling or an inability to empty the bladder during active urination. Medical therapy is directed at the smooth, and sometimes skeletal, muscle of the urethra to either improve contraction or enhance relaxation. Some surgical and cystoscopic interventions may improve outcome in these patients when medical therapy fails.

Dr. Byron is a clinical professor in the Department of Veterinary Clinical Sciences at The Ohio State University. Her primary area of research and practice interest is lower urinary tract disease of the dog and cat, particularly disorders of urination.

References:

- Byron JK, Taylor KH, Phillips GS, Stahl MD. Urethral sphincter mechanism incompetence in 163 neutered female dogs: diagnosis, treatment, and relationship of weight and age at neuter to development of disease. J Vet Intern Med. 2017;31(2):442-448. doi: 10.1111/jvim.14678.

- Forsee KM, Davis G, Mouat EE, Salmeri KR, Bastian RP. Evaluation of the prevalence of urinary incontinence in spayed female dogs: 566 cases (2003-2008). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2013;242(7):959-62. doi: 10.2460/javma.242.7.959.

- Thrusfeld MV, Holt PE, Muirhead RH. Acquired urinary incontinence in bitches: its incidence and relationship to neutering practices. J Small Anim Pract. 1998;39:559-566.

- Reichler IM, Hung E, Jöchle W, et al. FSH and LH plasma levels in bitches with differences in risk for urinary incontinence. Theriogenology. 2005;63:2164-2180.

- Reichler IM, Jöchle W, Piché CA, Roos M, Arnold S. Effect of a long acting GnRH analogue or placebo on plasma LH/FSH, urethral pressure profiles and clinical signs of urinary incontinence due to sphincter mechanism incompetence in bitches. Theriogenology. 2006;66:1227-1236.

- Adams WM, DiBartola SP. Radiographic and clinical features of pelvic bladder in the dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1983;182(11):1212-1217.

- Acierno MJ, Labato MA. Canine incontinence. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet. 2006;28:591-598.

- Holt P. Urinary incontinence. In: Holt P (Ed): Urological Disorders of the Dog and Cat: Investigation, Diagnosis and Treatment. London, UK: Manson Publishing; 2008:134-159.

- Reeves L, Adin C, McLoughlin M, Ham K, Chew D. Outcome after placement of an artificial urethral sphincter in 27 dogs. Vet Surg. 2013;42(1):12-18. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-950X.2012.01043.x.

- Barth A, Reichler IM, Hubler M, Hässig M, Arnold S. Evaluation of long-term effects of endoscopic injection of collagen into the urethral submucosa for treatment of urethral sphincter incompetence in female dogs: 40 cases (1993-2000). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2005;226(1):73-76.

- Byron JK, Chew DJ, McLoughlin ML. Retrospective evaluation of urethral bovine cross-linked collagen implantation for treatment of urinary incontinence in female dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2011;25(5):980-984.

- Rawlings C, Barsanti JA, Mahaffey MB, Bement S. Evaluation of colposuspension for treatment of incontinence in spayed female dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2001;219(6):770-775.

- Aaron A, Eggleton E, Power C, Holt PE. Urethral sphincter mechanism incompetence in male dogs: a retrospective analysis of 54 cases. Vet Rec. 1996;139:542-546.

- Palerme JS, Mazepa A, Hutchins RG, Ziglioli V, Vaden SL. Clinical response and side effects associated with testosterone cypionate for urinary incontinence in male dogs. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2017;53(5):285-290.

- Plumb DC. Plumbs Veterinary Drug Hanbdbook, 9th ed. Ames, IA: Wiley-Blackwell; 2018.

- Lane IF, Westropp JL. Urinary incontinence and micturition disorders: pharmacologic management. In Kirk’s Current Veterinary Therapy, 14th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier, 2009;955-959.