Commentary: Could a DVM-MS degree open the door to One Health?

Modern medicine has reshaped our world. We think the next revolution could be in recognizing the interdependence of all species and all life, and creating a new dual-degree to educate the leaders of that field for the future.

Is it finally time for the industry and the profession to shift veterinary medicine to include more than pets? (Orlando Florin Rosu / stock.adobe.com)

“Between animal and human health there is no dividing line-nor should there be. The object is different, but the experience constitutes the basis of medicine.” -Rudolph Virchow, 19th-century physician-pathologist

“One-health is the integration of multiple disciplines working locally, nationally and globally to attain optimal health for people, animals and the environment.” -AVMA, 21st-century interpretation

We no longer live in a time when the health professions and environmental sciences can function as separate entities. People, animals and plants constitute a single interdependent, global ecosystem. Biological threats-naturally occurring, accidental and deliberate-are among the most serious dangers facing the nation and the world.1 Approximately 75 percent of emerging infectious diseases in humans are zoonotic, and most have wildlife reservoirs, yet the human and animal health professions as well as the environmental sciences remain uncoordinated. Veterinary medicine is largely overlooked in human health, as is evident from the small numbers of veterinarians employed in the global health sector.2

There is a critical need for veterinarians with a deep understanding of transdisciplinary, multispecies medicine that is not being achieved with the traditional system of veterinary education.2,3 Given the fact that approximately 70 percent of U.S. veterinary graduates enter clinical practice, veterinary education is designed predominantly around individual animal medicine, especially companion animals.2,3 In the overcrowded curriculum, there is no room for in-depth One Health education. The academic institutions need to find new ways of thinking about One Health and devising workable solutions. The colleges of veterinary medicine are the gatekeepers of the profession, and only they can create educational programs that will produce a cadre of veterinarians thoroughly educated and trained for leadership roles in ecological health sciences and who will advance the role of veterinary medicine in global society.

The White House recently announced (September 18, 2018) a new national biodefense strategy4 that includes “advancing and sustaining a highly skilled public and veterinary health workforce” as well as “promoting global health security and trans-disciplinary collaboration.” It is not clear when this initiative will begin and whether actual changes to veterinary education are intended. However, the program offers the likelihood of the veterinary profession having a larger footprint in the global health arena and offers justification and possible funding for the educational initiatives we are suggesting.

We believe that One Health education in the veterinary curriculum should be a two-tiered system, with those who will work at the frontiers of ecological medicine receiving a specialized education, while the majority are educated more generally:

General: Integrate One Health principles into all four years of veterinary education, thus ensuring that all graduates understand the connection between the practice of veterinary medicine and environmental health, regardless of their career focus. This goal can be reached through minor changes in the veterinary curriculum.

Specific: Provide advanced education and training in interdisciplinary environmental health sciences to a chosen subset of veterinary students. This cannot be done using the traditional all-purpose model of veterinary education-only through curricular differentiation (i.e. tracking).3,5

A proposed One Health track

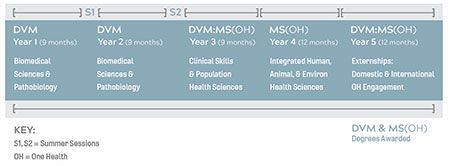

After completing years one and two of the standard veterinary curriculum, a select group of students would be enrolled in a DVM-MS One Health dual-degree program of three years' duration (Figure 1). Selection criteria and enrollment numbers would be the prerogative of the faculty and administrators at each college. (Interest in careers other than private practice seems to be growing,5 so colleges should target these students.)

Figure 1: A prospective One Health curriculum

Year three of the DVM-MS program would covers advanced multispecies, multidiscipline clinical courses required for the DVM degree, plus elective courses in environmental health sciences.

Year four would entail a 12-month nonthesis master's degree program in One Health, incorporating such areas as human and comparative medicine, environmental sciences, animal conservation, epidemiology, disease ecology, microbiology, toxicology, zoonoses and emerging infections, agroterrorism, food safety and security, and sociology. The year would be taught jointly by veterinary college faculty, medical school faculty, environmental scientists and conservation biologists, as appropriate.

As far as possible, the dual curriculum should be offered in an interactive seminar format rather than didactic lectures, thus developing students' personal skills such as communication, problem-solving, team-building and leadership. As an integral part of the MS degree, each candidate would be required to write an essay of publishable quality on a contemporary One Health topic of his or her choice. Students would be permitted to transfer an appropriate number of credits from DVM courses to fulfill master's degree requirements.

Year five of the DVM-MS program would be a year of core and elective rotations in medicine and surgery required for the DVM degree. Some segments would be located at the veterinary teaching hospital, while others would be extramural, including environmental health locations. This arrangement would permit the establishment of standardized, constantly rotating externships. Every student should undertake at least one major international assignment. (Few experiences can teach like world travel-studying among other cultures, languages and practices.) Externships may vary in length, according to each situation, but must be more than a superficial visit.

In some instances, it may be possible to award academic credit for students' prior experiences, including military service, thus giving educational value to One Health knowledge and skills already acquired in the field. Such an arrangement would need to be well-documented and strictly limited, perhaps to a maximum of five or six credits.

After completing year five, the DVM and MS degrees would be conferred.

The degree must be worth it

Assessing the benefits and costs of earning the dual degree is vital. Presumably, the combined DVM-MS degree in One Health would provide significant employment advantages for veterinary graduates to enter directly into the public sector. Nevertheless, the extra time and money are considerable. An important benefit of this model is that the MS degree is earned in just one year, compared to an independent master's degree that typically would take two years to complete. Another cost-saving measure would be to cut preveterinary education from four years to two years. In addition, students could undertake up to six months' paid employment during the summer months between academic years one and two, and two and three.

Participating colleges could offer student stipends, tuition waivers and travel allowances using income derived from grants and philanthropic endowments. Where possible, student awards could be structured so they're matched, in cash or in kind, by extramural host organizations. An excellent strategy would be to form a consortium of veterinary colleges, medical schools and environmental science departments that would create a fully integrated One Health curriculum and secure multiple resources and opportunities beyond what any institution could achieve individually. Participants would be true partners rather than competitors.

An important role of academia is to offer continuing education and training to practicing veterinarians. Thus, the veterinary colleges should:

- Give occasional seminars in One Health to local veterinary associations.

- Provide certificate-granting extended education for veterinarians wishing to explore new career opportunities in population health sciences.

- Permit veterinarians who are able to invest the time and expense to enroll in Year 4 of the dual-degree program and earn the MS degree in One Health.

It would be essential for each participating college to appoint an experienced faculty member as leader of its One Health education initiatives. Success would depend on exceptional inter-institutional and interpersonal trust and cooperation.

A 'new medicine'

Veterinary medicine is justifiably proud of its history of providing excellent service to society. However, the profession clings relentlessly to its past successes, even amidst compelling evidence of the need to change. There is little sense of urgency, which is why the profession continues to talk about One Health instead of practicing it. Change takes more than good intentions. If our socioeconomic environment is holding us back, we must do everything within our power to change it. If we cannot change the environment, we need to change ourselves. This is not without risk. Even when it is for the better, radical change is always accompanied by temporary loss of security. The profession's future depends on closing the gap between what we are and what we could become. Veterinary medicine has barely scratched the surface of its One Health potential.

It has been the authors' privilege to live and work through a time of transition. During the past half century, the veterinary profession has advanced in two remarkable ways. One is the immense growth in our understanding of health and disease-what we call medicine. The other is our recognition of the interdependence of human, animal and environmental biology-what we call One Health. That's a “new medicine” in the making, but one slow to develop, having been achieved in varying degrees at only a few academic institutions.1,2,3 The veterinary colleges have a duty to produce appropriate numbers of veterinary graduates with the qualifications needed to fill the many roles for veterinarians in society, including One Health/ecological medicine. It is conceivable that this field could eventually develop into a veterinary specialty college.3 And it is possible for veterinary medicine to lead the medical world in this endeavor if it chooses to do so.3

The curriculum we have described is not the only possible representation of multidisciplinary health education. A variety of independent master's and doctoral degrees have existed for some time, including the master of public health (MPH), which is offered at a number of veterinary colleges and medical schools. However, we suggest that veterinary medicine needs to reach beyond public health. We suggest that our proposed DVM-master's degree in One Health is more holistic and covers the entire spectrum of ecosystem health (literally the health of the planet) of which public health is one component part.6 Substantial changes in veterinary education are urgently needed if our academic institutions and their graduates are to make optimal contributions to global health in the future.

And while the veterinary colleges are the profession's “gatekeepers,” it is the organized veterinary profession itself that holds the “keys” (accreditation and licensure) that can unlock future possibilities. For the One Health paradigm to succeed, unwavering support from leaders of the AVMA, AAVMC and other governing bodies will be essential. The future success of veterinary medicine depends on all of is.

“It is no use saying, ‘We are doing our best.' You have got to succeed in doing what is necessary.” - Winston Churchill

References

1. Association of American Veterinary Medical Colleges. Agenda for Action: Veterinary Medicine's Role in Public Health and Bio-defense. J Vet Med Educ 2003;30(2).

2. Hird D, King L, Salman M, and Werge R. A crisis of lost opportunity: Conclusions from a symposium on challenges for population health education. J Vet Med Educ 2002;29(5):205-209.

3. Nielsen NO, Eyre P. Tailoring veterinary education for the future by emphasizing one-health. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2017;251:502-504.

4. A New Direction against Biological Threats. info@mail.whitehouse.gov

5. Eyre P, Ragan VE. Choosing a career beyond private practice (lett). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2018;253:699.

6. Kahler SC. Environment: the bedrock of one-health. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2018;252:903-905.

Dr. Peter Eyre is professor and dean emeritus at the Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine in Blacksburg, Virginia. Dr. Robert Brown owns Cherrydale Veterinary Clinic in Arlington, Virginia. Address correspondence to Peter Eyre at cvmpxe@vt.edu.