Conflict: How to overcome approval addiction

How to handle tough situations in the office.

You're reviewing your monthly financial reports for your practice and notice a significant jump in your accounts receivable. On further investigation, you find that this increase consists mainly of cases seen by your newest associate veterinarian and that this trend has been developing ever since this doctor came on board. Obviously, you must address the issue. How will you handle it?

An otherwise excellent assistant is frequently tardy. Two other employees are experiencing an ongoing personality conflict that affects the rest of the office. Will you confront them?

A long-term client who previously requested "temporary" credit has fallen behind on his account and yet wants to continue to receive services for his chronically ill pet. What will you do?

All these scenarios share a common thread: They require a potentially difficult conversation between you and another person. Even in practices with a full-time office manager, these situations often require input or final disposition by the practice owner. I speak from experience—I've been far too patient with a chronically tardy employee and I once continued to offer discounted services to a client with a diabetic dog whose account was falling further and further behind. If you often shy away from confrontation because of a fear of hurting someone's feelings, follow this plan to overcome your approval addiction.

Personnel issues

Fight or flight

Conflict resolution. Confrontation. Correction. Discipline. Policy enforcement. Boundary setting. Even the names we use for these types of situations sound unpleasant. That's because they represent some of the most emotionally draining aspects of owning or managing a veterinary practice—especially considering how very little training veterinarians receive in dealing with such matters. As a result, a discussion of how to proceed through these conversations might be beneficial.

There are two ways to look at the question "How will you handle it?" First, you can emphasize the word "handle"—i.e., "How will you handle it?" This approach focuses on the external factors surrounding tough conversations: the time of day, the seating arrangement, and so on. It might also prompt you to think about the actual words you'll speak to the other person and how they'll help you achieve your desired result.

You can also emphasize the word "you"—"How will you handle it?" Phrased this way, the question refers more to your internal processes—your perceptions and emotions surrounding the conflict. Though these internal realities are more difficult to discuss objectively, they're critical to the overall, long-term outcome of these conversations—perhaps even more so than external considerations.

The bottom line

Change starts with you

Consider the examples at the beginning of this article, or recall similar situations you've faced in the past. Now, try to think through your emotional reactions. Did you feel angry about being bothered with personnel problems in addition to everything else you had to deal with? Did the thought of telling a client "no" make you anxious? Were you resentful when you had to enforce policies and expectations because it seemed like people were trying to take advantage of you? Understanding your emotions as you approach difficult conversations is important. If you're not careful, these emotions can influence your communication in ways that aren't conducive to achieving your desired outcome.

And what is your desired outcome, anyway? This is something else you need to think through during times of conflict. More specifically, ask yourself this question: What are you after—acceptance or approval? In other words, is your goal to get clients and employees to abide by your hospital's policies? Or do you want them not only to abide by your policies but also to agree that your policies are wise and just?

As you might imagine, the second goal is difficult to achieve. It's also unnecessary—and potentially harmful. Employees, associates, and clients don't need to approve of your policies to abide by them and contribute to your hospital's profitability and efficiency. Further, if you approach a confrontational situation needing the other person's approval, you are by default increasing the pressure on that person and, thus, the tension in the room.

In addition to trying to change the other person's actions, you're also trying to make him or her think like you do. The odds of this happening are slim, and the cost of trying to achieve it can be high—especially if you resort to lecturing and preaching.

Numbers do not lie

By contrast, if you approach a conflict situation without seeking the other person's approval, you're starting from a more emotionally secure place, which lowers the tension in the room. Remember, however, that your freedom from approval addiction must be genuine. Angrily informing the other person through gritted teeth, "I don't care whether you like it or not!" is a blaring indication that you do, indeed, care.

"We need to talk"

After defining your desired outcome, it's time to form a plan of action, giving thought to how you'll actually talk to and interact with the other person. The best thing to do here is to "stay on your side of the street." In other words, don't stray over to the other person's side and start throwing personal-attack punches.

For starters, this means stating the facts without value judgments or personal criticism. If you're talking to your associate, you might say, "I've noticed lately that our receivables have been increasing and that it's mostly a result of cases you've seen."

Or you could say to your tardy employee, "From the time cards I see that you've been having trouble getting to work on time." These are the facts—they're objective and verifiable (if, of course, they've been properly documented). These facts are important because they represent a potential problem for your practice. You've stated them without any emotion, insult, or aggression.

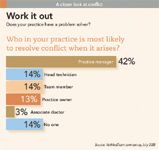

A closer look at conflict

Beginning the conversation this way doesn't guarantee that the other person won't become uncomfortable or defensive, but at least you haven't added to the tension with unnecessary emotions and hurtful words. If you sense discomfort on the other person's part, it can be helpful to ask him or her to repeat what you've said. Again, this may not ease anyone's discomfort, but it can help prevent misunderstanding.

Your next step is to ask the other person what he or she believes are the reasons for the facts. For example, ask the associate why she thinks her receivables have jumped, or ask the employee why he's having trouble getting to work on time.

Realize that this step isn't always appropriate—such as in the case of a repeat offender. At other times, though, this query can yield insight that's helpful both to you and the other party. The associate may come to understand the reasons for her behavior; you may become aware of a simple solution to the employee's tardiness problem.

Finally, you need to clearly state the specific changes in behavior you expect. Sometimes it helps to explain why the changes are necessary. For example, your associate may benefit from knowing that you pay taxes on accounts receivable whether the practice gets paid or not. But the reasons behind your expectations don't always need to be spelled out.

Your employee is required to be on time, period. Your client with a past-due balance can't continue to run up her bill; end of discussion. What is absolutely necessary is that you clearly state (and document) exactly what you will and won't accept and outline the consequences for failed compliance. The key here is to assert your authority without being unnecessarily aggressive.

Confronting employees and declining clients' outrageous requests can be extremely stressful for some of us who lean toward approval addiction. Taking time to become aware of your own emotional starting point, setting realistic expectations for the outcome, and staying on your side of the street can make for a safer, less harrowing experience.

Dr. Gene Maxwell owns and practices at Town & Country Animal Hospital in McMinnville, Tenn. Send questions or comments to ve@advanstar.com or post your comments on our message boards at dvm360.com.